Indeterminate primary growth originates in apical meristems

Because apical meristems can perpetuate themselves indefinitely, a stem or root can continue to lengthen and grow indefinitely; in other words, growth of the plant body as a whole is indeterminate. All plant organs arise ultimately from cell divisions in apical meristems, followed by cell expansion and differentiation. Several types of apical meristems play roles in organ formation:

Shoot apical meristems supply the cells for new leaves and stems. In addition to the main stem of the plant, each branch has its own shoot apical meristem. Shoot apical meristems are also called vegetative meristems, because they give rise to vegetative tissues (leaves, stems, and roots).

724

When the plant is ready to flower, one or more of its shoot apical meristems are transformed into inflorescence meristems, and these in turn develop floral meristems. (Chapter 37 is dedicated to the reproduction of flowering plants; inflorescence and floral meristems are discussed in Key Concept 37.2.)

Root apical meristems supply the cells that extend roots, enabling the plant to penetrate and explore the soil for water and minerals. Each type of root (i.e., the taproot, a lateral root, or an adventitious root; see below) has its own root apical meristem.

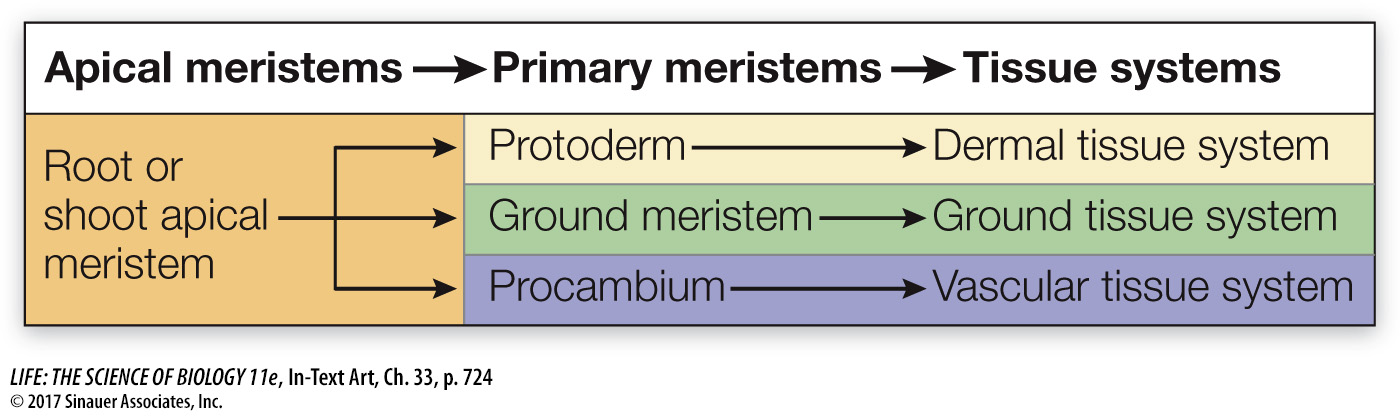

Apical meristems in both the shoot and the root give rise to a set of primary meristems, which produce the tissues of the primary plant body. From the outside to the inside of the shoot or root, the primary meristems are the protoderm, the ground meristem, and the procambium (see Figure 33.10A). These meristems, in turn, give rise to the three tissue systems:

Because meristems can continue to produce new organs throughout the lifetime of the plant, the plant body is much more variable in form than the typical animal body, which produces each organ only once.

Let’s look more closely at how the root apical meristem produces the root system.