The root system anchors the plant and takes up water and dissolved minerals

Water and minerals enter most plants through the root system, which is located in the soil. Because light does not penetrate the soil, roots typically lack the capacity for photosynthesis. Although hidden from view, the root system is often larger than the visible shoot system. For example, the root system of a 4-month-old winter rye plant (Secale cereale) was found to be 130 times longer in total than the shoot system, with almost 13 million branches that had a cumulative length of more than 500 kilometers!

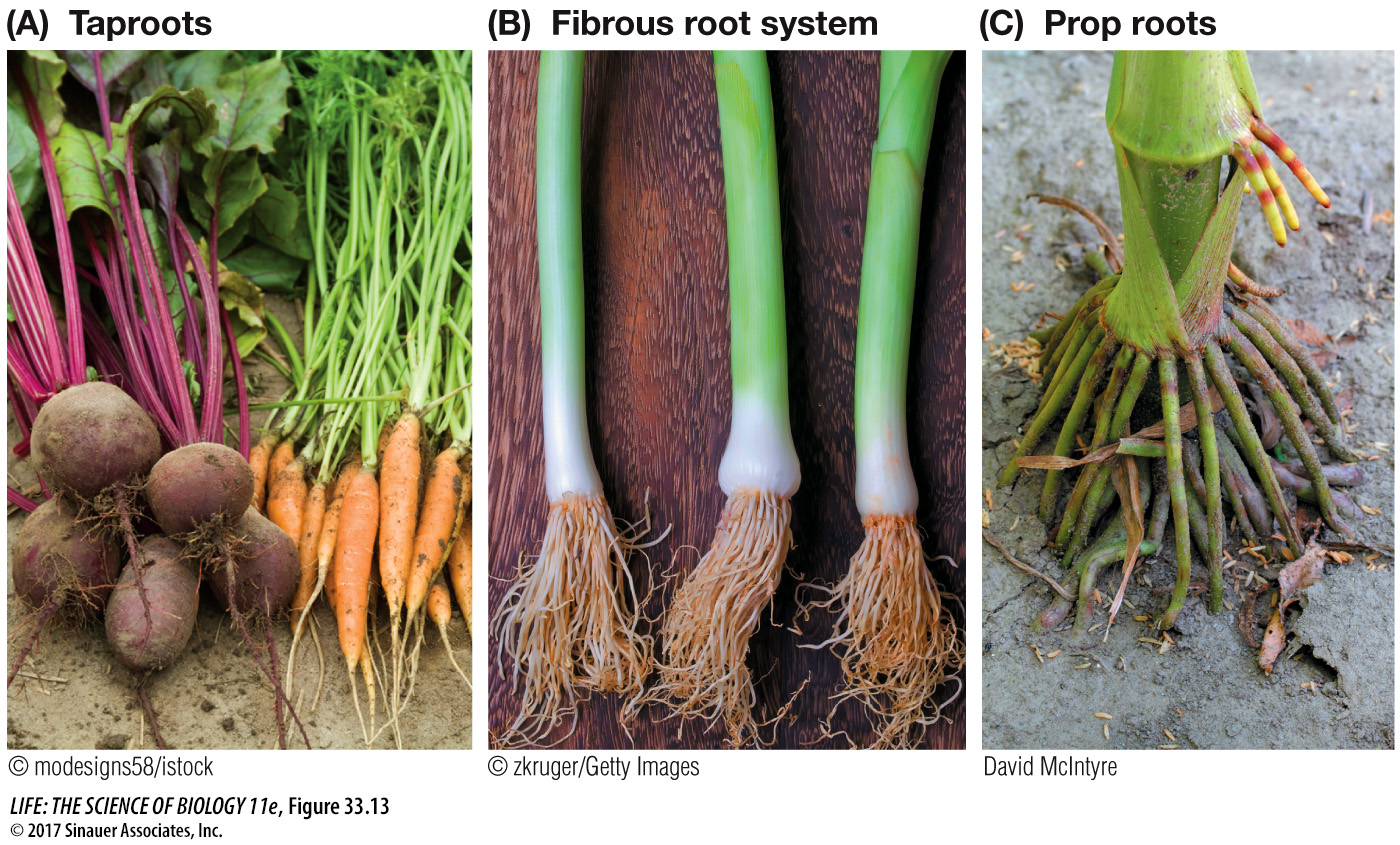

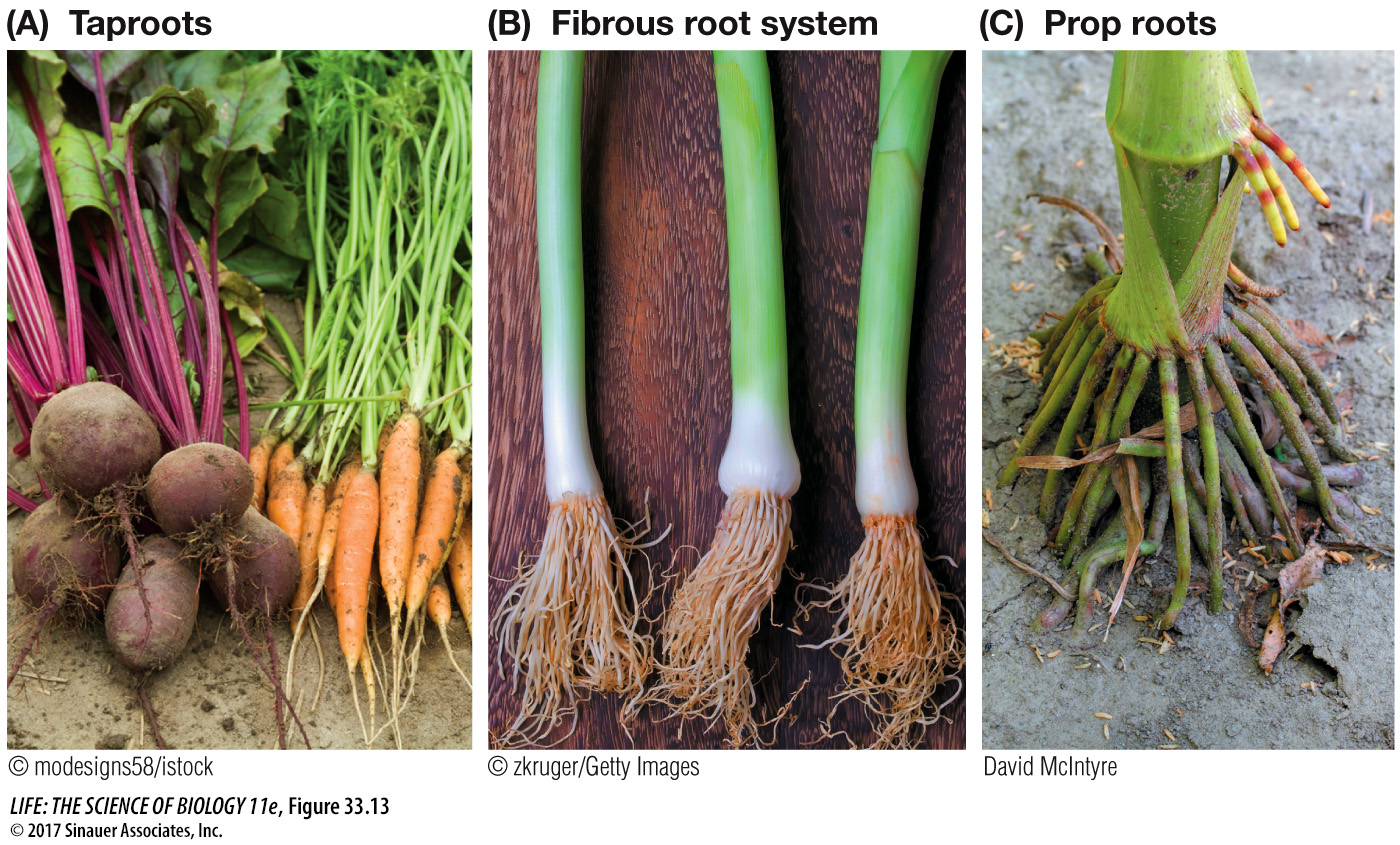

Angiosperm root systems develop from the embryonic root, called the radicle. From this common starting point, the root systems of monocots and eudicots develop differently. Following seed germination, the radicle of most eudicots develops as a primary root called the taproot, which extends downward by tip growth and outward by initiating lateral roots. The taproot and the lateral roots form a taproot system, which can take a variety of forms. For example, the taproot itself often functions as a nutrient storage organ, as in carrots (Daucus carota), sugar beets (Beta vulgaris), and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) (Figure 33.13A).

Figure 33.13 Root Systems of Eudicots and Monocots (A) The taproot systems of eudicots, such as carrots and sugar beets, contrast with (B) the fibrous root system of a leek and (C) the adventitious prop roots of corn.

In contrast, the primary root of monocots (and some eudicots) is short-lived. Because they originate from the stem at ground level or just below, the roots of a typical monocot are called adventitious (“arriving from outside”) roots, and they form a fibrous root system composed of numerous thin roots that are all roughly equal in length (Figure 33.13B). Many fibrous root systems have large surface areas for the absorption of water and minerals. A fibrous root system clings to soil very well. The fibrous root systems of grasses, for example, may protect steep hillsides where runoff from rain would otherwise cause erosion.

In some plants—corn, banyan, and pandanus trees, for example—adventitious roots grow down from above the ground and function as props to help support the shoot system (Figure 33.13C). These prop roots have evolved for different reasons in different species. For example, some monocots may develop prop roots because they are unable to support aboveground growth through the thickening of their stems. Pandanus trees often grow near coastal beaches, where their prop roots help provide support in very sandy soils. Banyans begin life as epiphytes (plants that grow on other plants) and then develop woody prop roots, which enable them to grow into huge trees.