Stomata control water loss and gas exchange

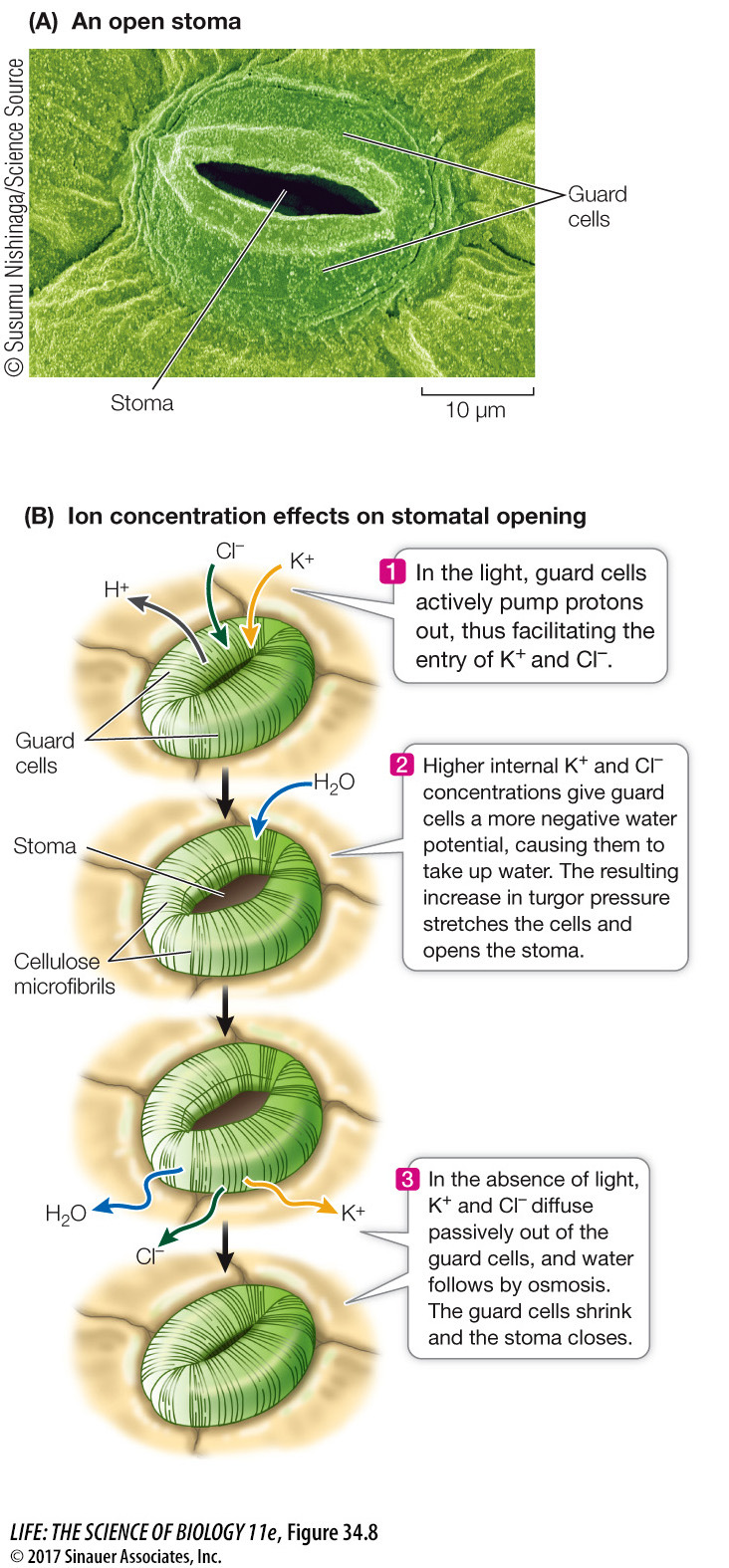

An elegant compromise has evolved in plants in the form of pores called stomata (singular stoma) in the epidermis of their leaves. A pair of specialized epidermal cells, called guard cells, controls the opening and closing of each stoma (Figure 34.8A). When the stomata are open, CO2 can enter the leaf by diffusion—

Most plants open their stomata only when the light intensity is sufficient to maintain a moderate rate of photosynthesis. At night, when darkness precludes photosynthesis, their stomata are closed; no CO2 is needed, and water is conserved. Even during the day, the stomata close if water is being lost at too rapid a rate.

Stomata are ancient structures; they have been found in plant fossils that are more than 400 million years old. For this reason they are thought to predate the evolution of leaves. Stomata are found in all vascular plants and in many nonvascular plants, including mosses (but not liverworts; see Chapter 27).

The stoma and guard cells seen in Figure 34.8A are typical of eudicots. Monocots typically have specialized epidermal cells associated with their guard cells. However, the principle of operation, which we will now describe in more detail, is the same for both monocot and eudicot stomata.