Parasitic plants take advantage of other plants

Approximately 1 percent of flowering plant species derive some or all of their water, mineral nutrients, and sometimes even photosynthate from other plants. These parasitic plants have evolved absorptive organs called haustoria, which invade the host and tap into the vascular tissues in the root or stem.

Parasitic plants are divided into two broad classes based on their nutritional interactions with their hosts. Hemiparasites can still photosynthesize but derive water and mineral nutrients from the living bodies of other plants. Perhaps the most familiar hemiparasites are the several genera of mistletoes. Mistletoes are green and carry on some photosynthesis, but they parasitize other plants for water and mineral nutrients and may derive photosynthetic products from them as well. Dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium americanum) is a serious parasite in forests of the western United States, destroying more than 3 billion board feet of lumber per year.

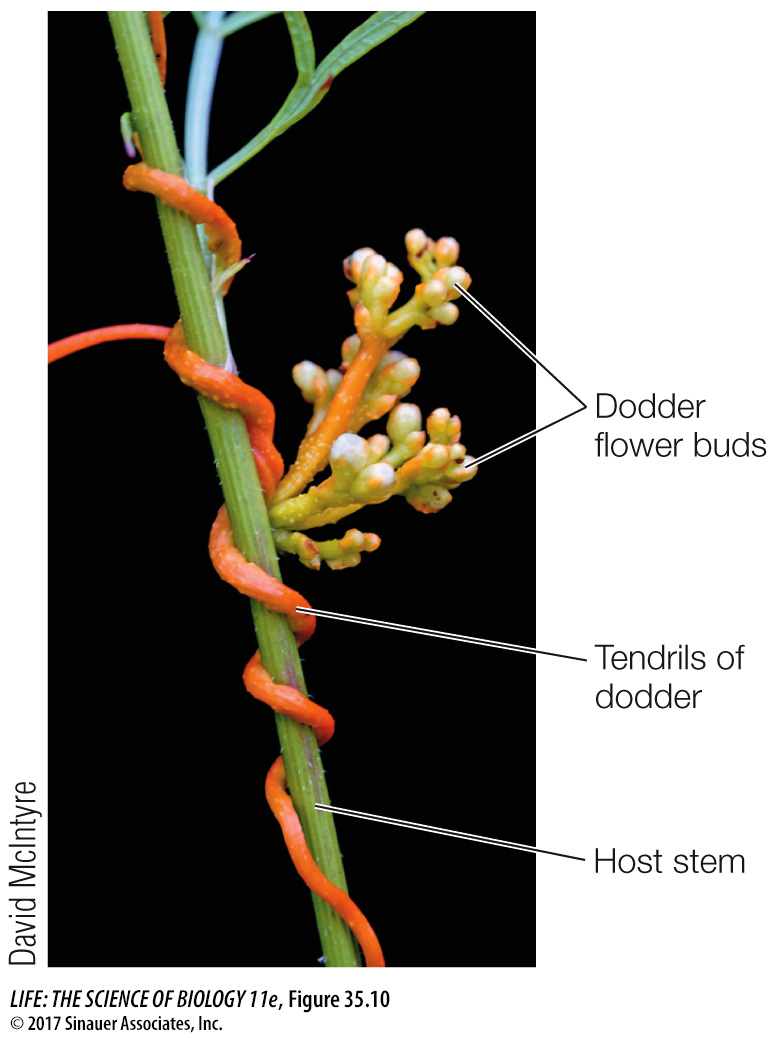

Holoparasites are completely parasitic and do not perform photosynthesis. They are taxonomically and morphologically diverse. Some, such as members of the dodder family, are plantlike in appearance, with small leaf remnants and flowers (Figure 35.10). Some holoparasites do not have leaves or stems because they spend most of their life cycle underground and only break the surface to flower.

Several parasitic plant species lack many of the genes normally present in the chloroplast genome (which in turn is only a remnant of the genome of the original endosymbiont from which the chloroplast evolved; see Key Concepts 5.5 and 26.1). These genes, which are needed for photosynthesis, have been lost because there is no evolutionary pressure to retain them. Thus while the parasitic lifestyle can be viewed as a free ride, for some plants it is also a one-