Flowering occurs at specific places and specific times

Plants fall into three categories depending on when they mature and initiate flowering, and what happens after they flower:

Annuals complete their lives in one year. This class includes many crops important to the human diet, such as corn, wheat, rice, and soybean. When the environment is suitable, these plants grow rapidly, with little or no secondary growth. After flowering, they use most of their materials and energy to develop seeds and fruits, and the rest of the plant withers away.

Biennials take 2 years to complete their lives. They are much less common than annuals and include carrots, cabbage, and onions. Typically, biennials produce only vegetative growth during the first year and store carbohydrates in underground roots (carrot) and stems (celery). In the second year they use most of the stored carbohydrates to produce flowers and seeds rather than vegetative growth, and the plant dies after seeds form.

Perennials live 3 or more—

sometimes many more— years. Maple trees can live up to 400 years. Perennials include many trees and shrubs, as well as wildflowers. Typically these plants flower every year but stay alive and keep growing for another season; the reproductive cycle repeats each year. However, some perennials (e.g., century plant) grow vegetatively for many years, flower once, and die.

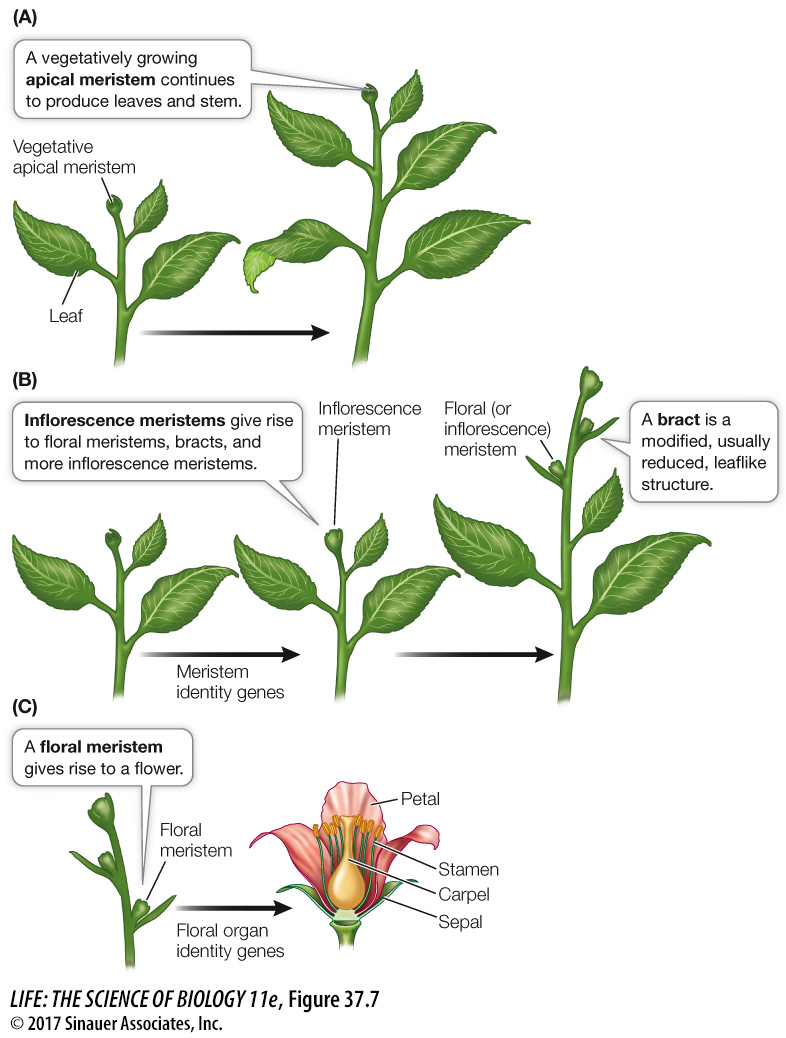

No matter what type of life cycle they have, angiosperms all make the transition to flowering. The first visible sign of a transition to the flowering state may be a change in one or more apical meristems in the shoot system. As you saw in Chapter 33, meristems have a pool of undetermined cells. During vegetative growth, a shoot apical meristem continually produces leaves, axillary buds, and stem tissues (Figure 37.7A) in a kind of unrestricted growth called indeterminate growth (see Key Concept 33.3).

Flowers may appear singly or in an orderly cluster that constitutes an inflorescence. If a vegetative apical meristem becomes an inflorescence meristem, it stops making leaves and axillary buds and produces other structures: smaller leafy structures called bracts, as well as new meristems in the angles between the bracts and the stem (Figure 37.7B). These new meristems may also be inflorescence meristems, or they may be floral meristems, each of which gives rise to a flower.

Each floral meristem typically produces four consecutive whorls or spirals of organs—