The mammalian thermostat uses feedback information

The thermoregulatory mechanisms and adaptations of endotherms are controlled by neural regulatory systems that integrate information from environmental and internal sources and then issue commands to the effectors that alter the heat content of the body. These regulatory systems are similar in principle in birds and mammals but differ in many details. Here we focus on the nervous system thermostats of mammals.

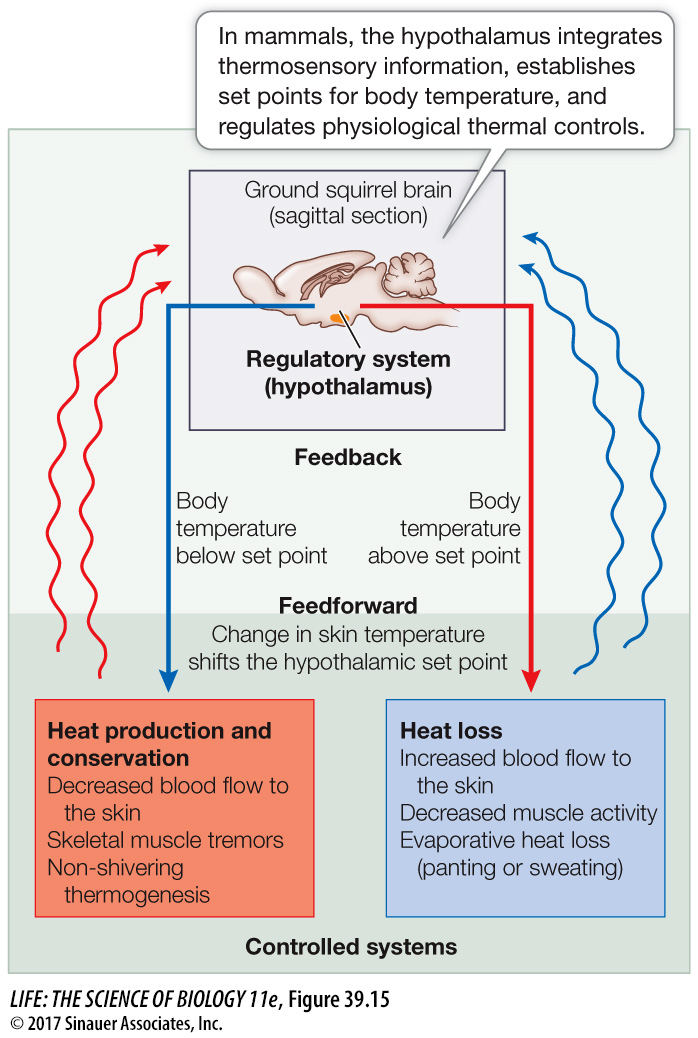

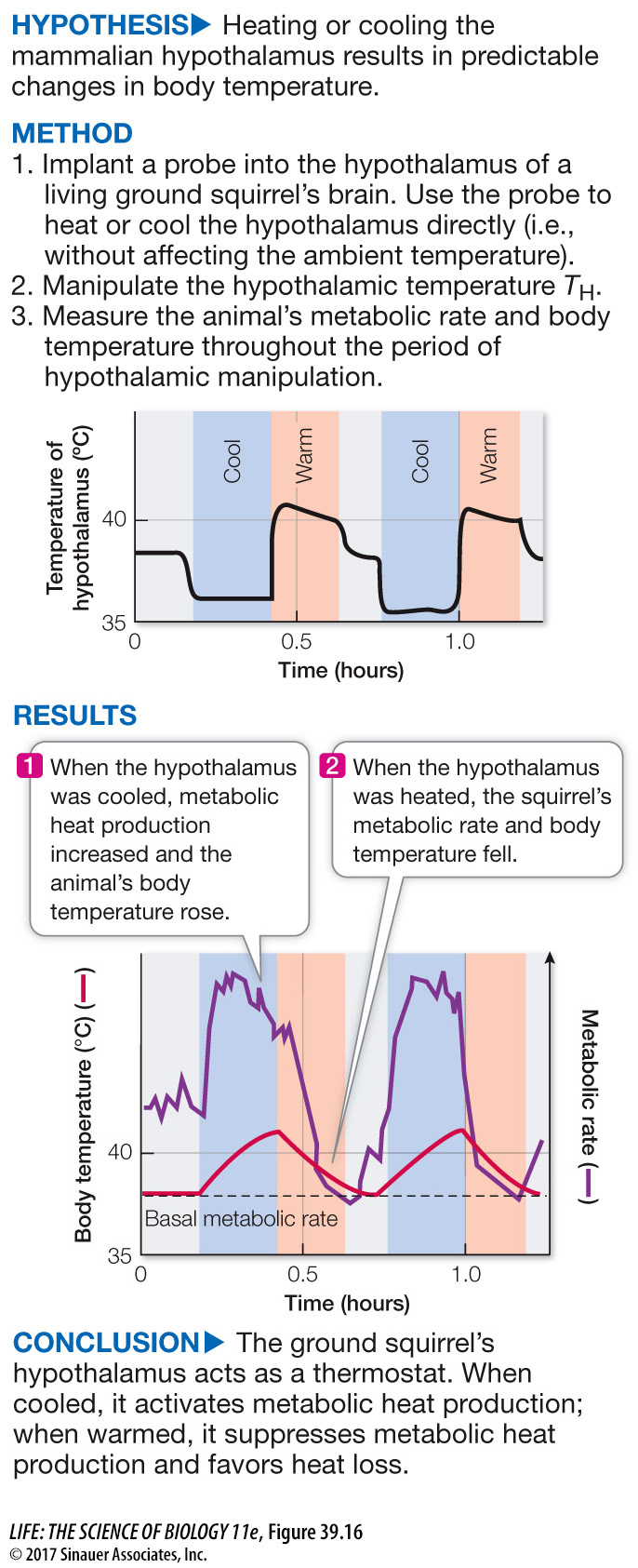

The major thermoregulatory integrative center of mammals is at the base of the brain in a structure called the hypothalamus (Figure 39.15). The hypothalamus is a key player in many regulatory systems of vertebrates. Experiments demonstrating its role have shown that slight cooling of the hypothalamus stimulates constriction of skin blood vessels and that stronger cooling increases metabolic heat production. As a result, cooling of the hypothalamus in an unchanging, thermoneutral environment will cause body temperature to rise. Conversely, hypothalamic heating causes the overall body temperature to fall (Figure 39.16).

Animation 39.1 The Hypothalamus

www.life11e.com/

experiment

Figure 39.16 The Hypothalamus Regulates Body Temperature

Original Paper: Heller, H. C., Colliver, G. W., and P. Anand. 1974. CNS regulation of body temperature in euthermic hibernators. American Journal of Physiology. 227:576–

A mammal’s hypothalamus was subjected directly to temperature manipulation. The body’s responses to the manipulations were as expected if the hypothalamus is the mammalian “thermostat.”

In mammals, the temperature of the hypothalamus itself is the major feedback signal. The hypothalamus generates set points for various thermoregulatory responses. When the temperature of the hypothalamus exceeds or drops below those set points, thermoregulatory responses are activated to reverse the direction of temperature change (see Figure 39.15). The system integrates other sources of information in addition to hypothalamic temperature. For example, temperature sensors in the skin register environmental temperature. A change in skin temperature is feedforward information that shifts hypothalamic set points; the set point for metabolic heat production is higher when the skin is cold and lower when the skin is warm.

Hypothalamic set points are higher during wakefulness than during sleep, and they are higher during the active part of the daily cycle than the inactive part, even if the animal is awake at both times. Even when an endotherm is kept under constant environmental conditions, its body temperature displays a daily cycle of changes in set point. This kind of cycle, a *circadian rhythm, is controlled by an internal biological clock.

*connect the concepts Key Concept 52.5 explains how a region of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus generates endogenous daily cycles called circadian rhythms that influence many physiological processes, including temperature regulation.