Some animals conserve energy by turning down the thermostat

Hypothermia is a below-normal body temperature. It can result from starvation (lack of metabolic fuel), exposure to extreme cold, serious illness, or anesthesia. In each of these cases, the drop in body temperature is unregulated. However, many birds and mammals undergo regulated hypothermia to survive periods of cold and food scarcity.

Hummingbirds, for example, are very small endotherms with a high metabolic rate, and going even a single day without food could exhaust their metabolic reserves. Hummingbirds and other small endotherms extend the period over which they can survive without food by dropping their body temperature by 10°C–20°C during the portion of day when they are normally inactive, thus lowering their metabolic rate and conserving energy. Daily bouts of regulated hypothermia are called daily torpor.

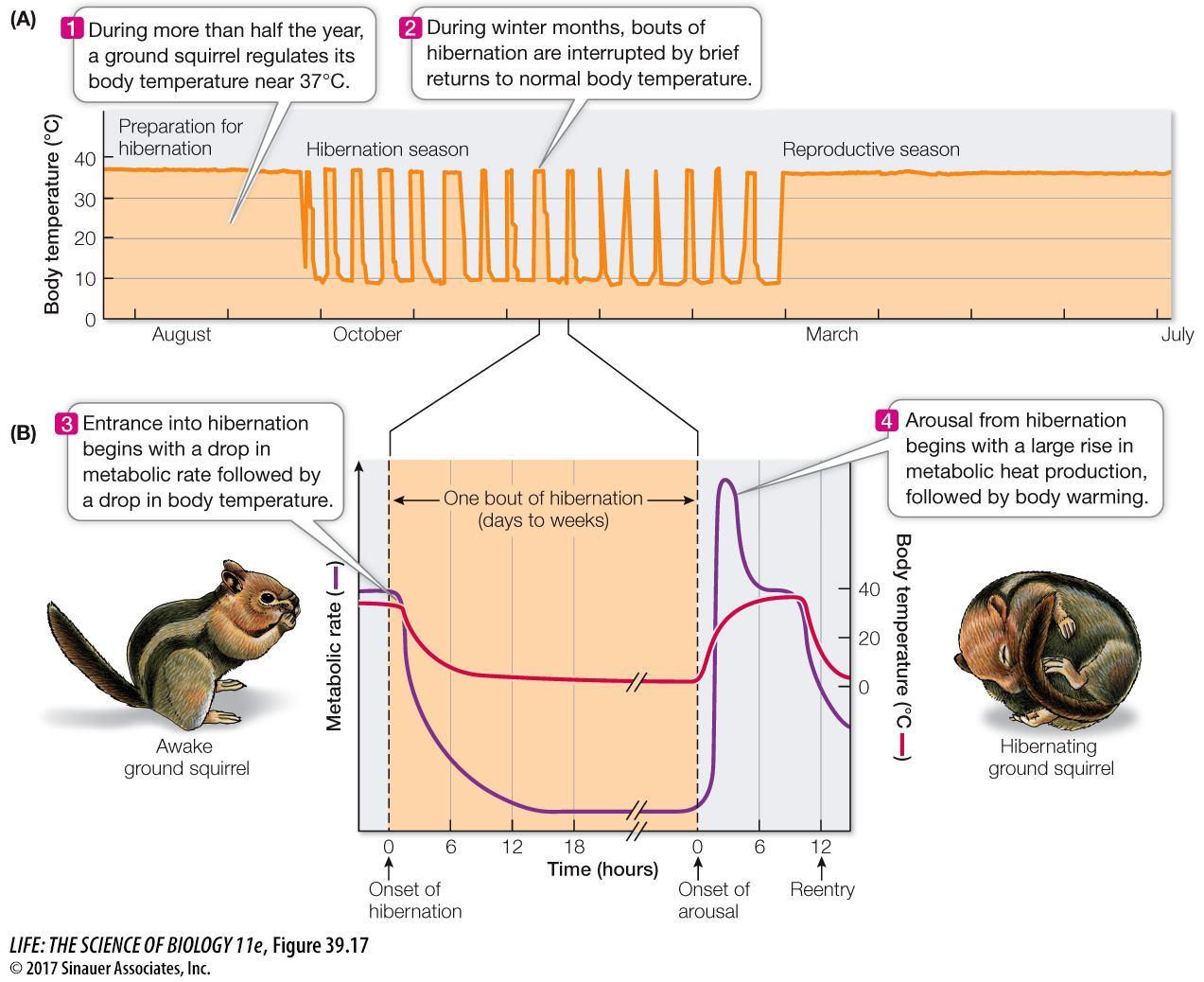

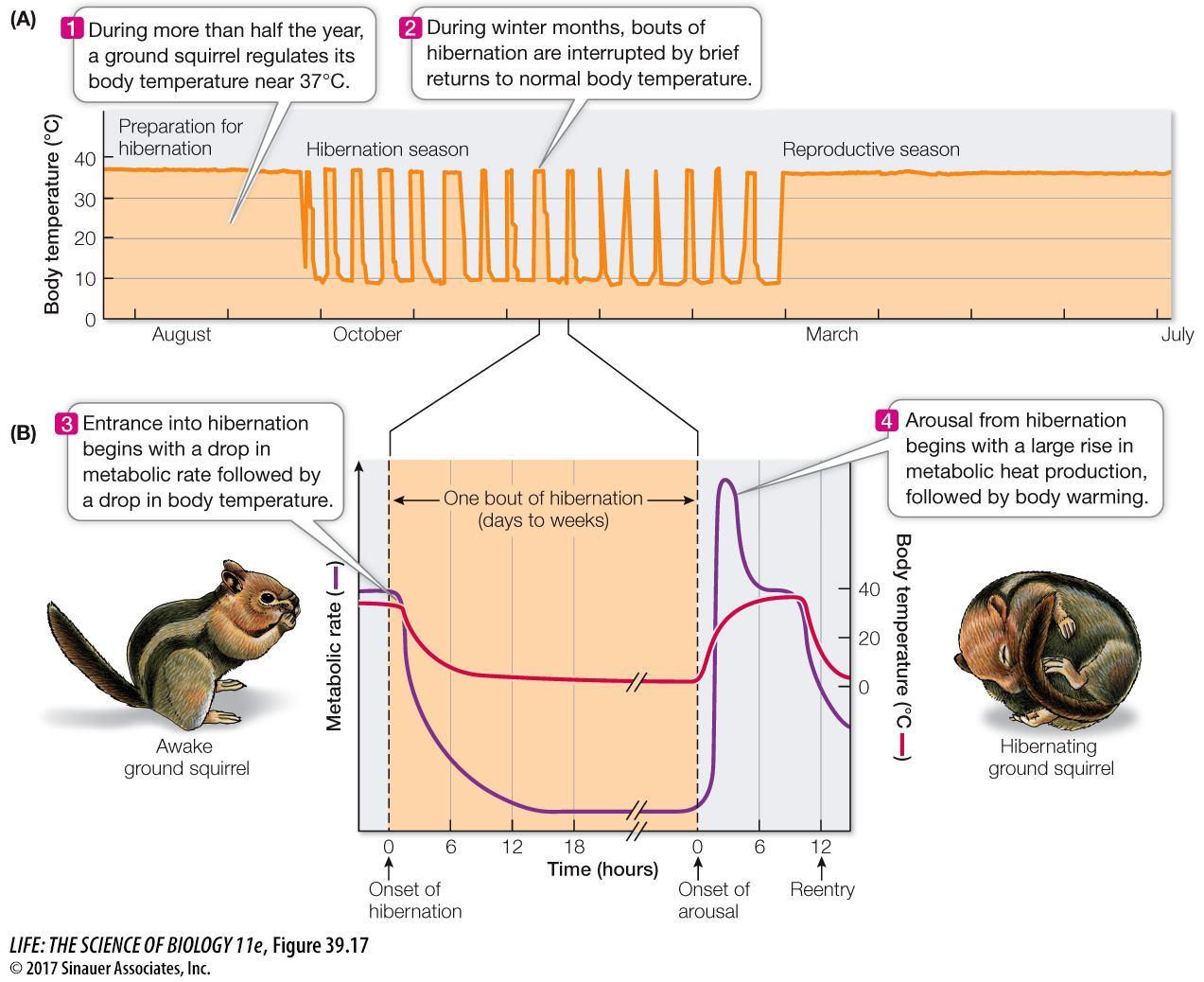

Regulated hypothermia that lasts for days or even weeks, during which the body temperature falls close to environmental temperature, is called hibernation (Figure 39.17). Many species of mammals, including bats, bears, marmots, and ground squirrels, hibernate, but only one species of bird (the common poorwill) has been shown to hibernate. The metabolic rate needed to sustain a hibernating animal may be only one-fiftieth its basal metabolic rate, and many hibernating animals maintain body temperatures close to the freezing point. Arousal from hibernation occurs when the hypothalamic set point returns to the normal level. The ability of animals to enter daily torpor or deep hibernation to reduce their thermoregulatory set point so dramatically probably evolved as an extension of the set point decrease that accompanies sleep in all mammals and birds.

Figure 39.17 Hibernation Patterns in a Ground Squirrel (A) During most of the year, the ground squirrel regulates its body temperature around 37°C. During winter months, however, these animals hibernate in underground burrows, living off stored fuel (in the form of either fat or cached food). (B) The metabolic demands for these stored fuels are decreased by bouts of torpor, during which body temperature drops close to that of the environment for long periods of time.