Apply What You’ve Learned

843

Review

39.4 The four avenues of heat exchange between an animal and its environment are radiation, convection, conduction, and evaporation.

39.5 Endotherms produce and conserve metabolic heat to offset heat loss in cold environments.

39.5 The basal metabolic rate (BMR) of an endotherm is the lowest metabolic rate necessary for biochemical and physiological processes of a resting animal.

Original Paper: Karpovich, S. A., Ø. Tøien, C. L. Buck and B. M. Barnes. 2009. Energetics of arousal episodes in hibernating arctic ground squirrels. Journal of Comparative Physiology 179: 691−700.

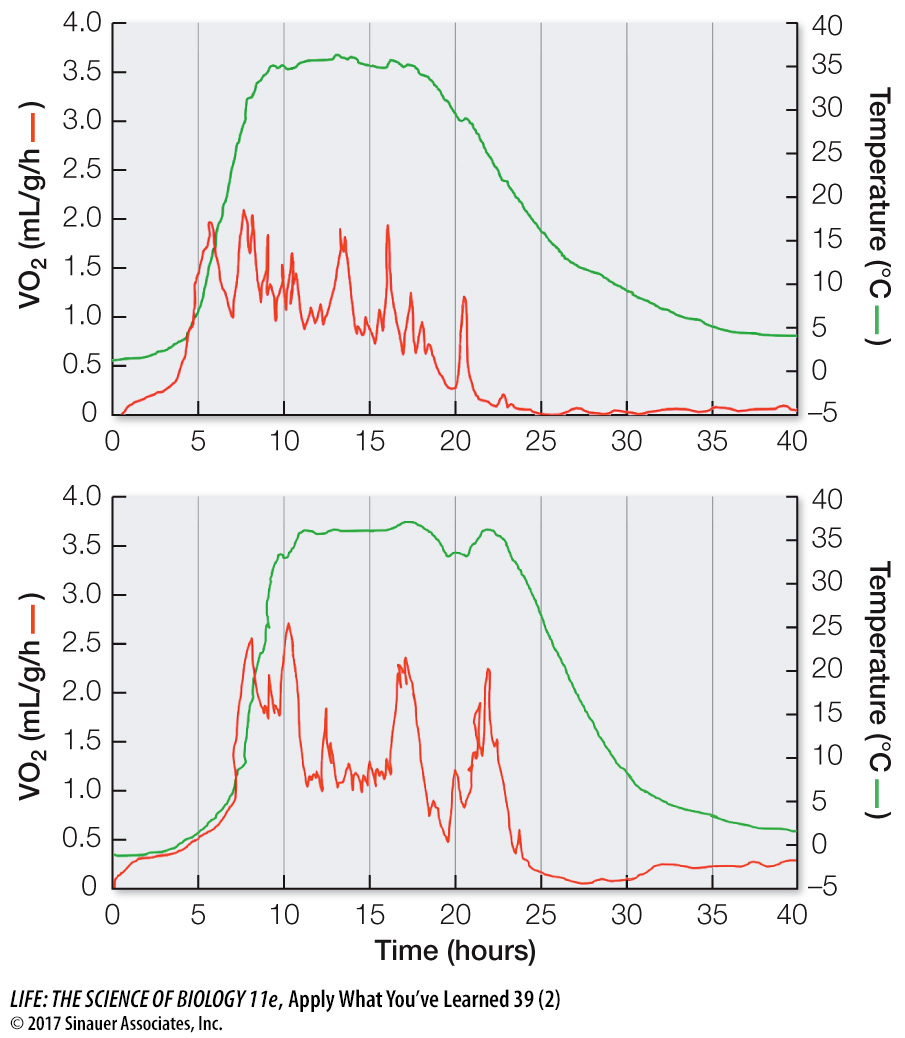

During winter, hibernating small mammals alternate between 1-

Researchers set up hibernation chambers for arctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus kennicottii). In nature, their winter burrows can reach –10ºC. The laboratory chambers were held at either +2ºC or –12ºC. All squirrels entered repeated bouts of torpor. During periods of arousal, body temperatures (Tb) and metabolic rates of individual squirrels were measured. Recordings of two individual squirrels are shown in the figure at right. They are representative of the squirrels assigned to the two groups.

The table reports the mean values during the rewarming phase for metabolic rate and body temperature plus or minus (±) the standard error for the two groups of squirrels at the different ambient temperatures. An asterisk (*) indicates that the mean values were significantly different from each other.

| Environmental temperature (°C) |

Starting body temperature (°C) |

Time to reach Tb= 30°C (h) |

Peak metabolic rate (mL O2/g/h) |

Total O2 consumption from initiation until Tb = 30°C (mL O2/g) |

Time to peak metabolic rate (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +2 | 2.37 ± 0.38 | 5.65 ± 0.51 | 2.65 ± 0.22 | 5.42 ± 0.28 | 4.25 ± 0.30 |

| –12 | –1.44 ± 0.40* | 8.20 ± 0.89* | 3.40 ± 0.18* | 7.71 ± 0.34* | 7.08 ± 0.65* |

Questions

Question 1

Did environmental temperature significantly affect the time to reach a Tb of 30°C? Did the initial body temperature affect the rate of rewarming? Explain your answer.

The group that reached a body temperature of 30°C in a significantly shorter time was the +2°C group. The starting temperature did have an effect on the rate of rewarming, which was 4.9°C/hr for the +2°C group and 3.8°C/hr for the –12°C group.

Question 2

Using the explanation in the chapter for an energy budget, explain why it took significantly longer for one group of squirrels to reach normal body temperatures and why their total O2 consumption was significantly different from that of the squirrels in the other group.

When an animal’s body temperature is constant, there is a balance between heat entering the body and heat leaving the body.

Therefore for body temperature to rise, heatin has to be greater than heatout. For both groups of squirrels in this experiment, heatin can only be coming from a single source, metabolism, since neither group has any source of radiant heat to absorb. However, the squirrels in the –12°C group encounter a much lower ambient temperature. Although they experience little conductive, convective, or evaporative heat loss when sequestered in a closed chamber, the –12°C group could experience greater radiative heat loss, which is a function of the difference between an animal’s surface temperature and the ambient temperature. In addition, the –12°C group is starting the rewarming process at a lower Tb. Thus more metabolic heat must be generated by the –12°C group to reach a Tb of 30°C thus requiring a greater total metabolic output and a longer time.

Question 3

During the warming period, the subjects engaged in limited gross or large body movement. Describe the mechanisms and processes these squirrels used to raise their body temperatures.

The two primary generators of metabolic heat in mammals are shivering and nonshivering heat production. Shivering is the rapid cycling of contractions of antagonistic muscles that do no work on the environment, thus all of the energy released from ATP during this process is released as heat. Nonshivering heat production comes from brown fat. This tissue contains many mitochondria and a good blood supply (thus the brown color in comparison to white fat). The brown fat mitochondria contain a protein, thermogenin, that uncouples the movement of protons from the production of ATP. Thus the fat substrate is metabolized, producing heat without producing ATP. These two mechanisms produce the heat to raise the body temperatures of the squirrels.