Thyroxine stimulates many metabolic processes

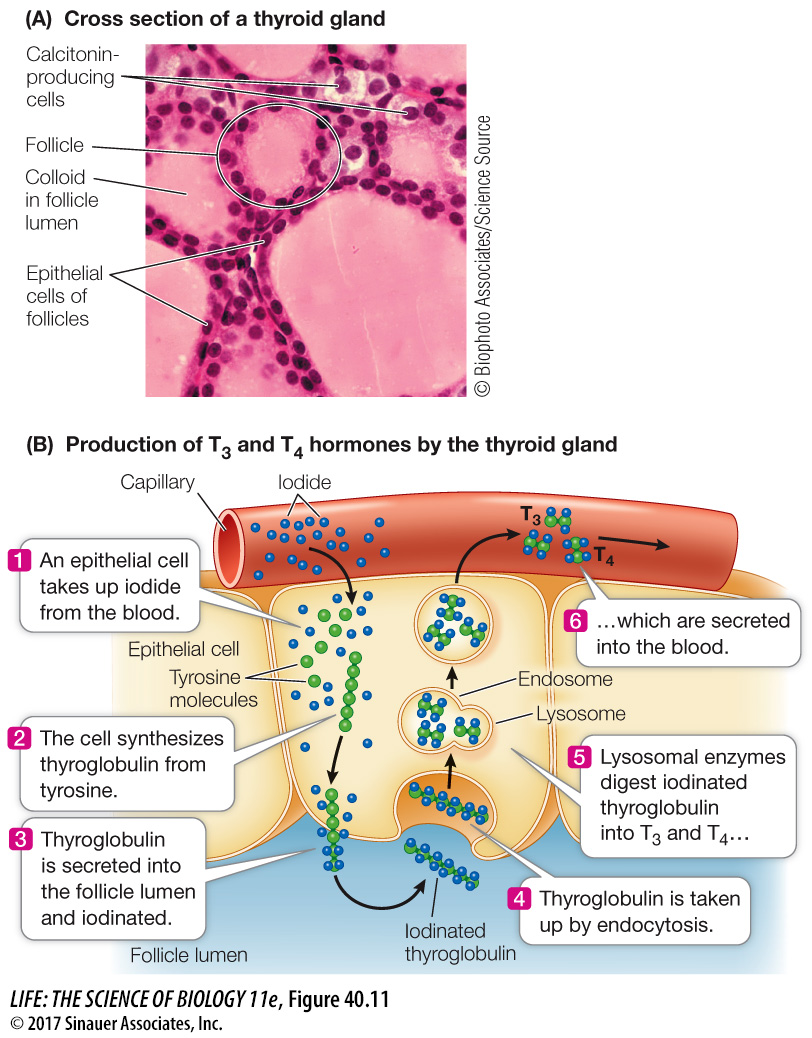

Thyroxine is produced and secreted by the thyroid gland. This gland wraps around the front of the windpipe (trachea) and expands into a lobe on either side (see Figures 40.5 and 40.12). There are two cell types in the thyroid gland, each of which produces a specific hormone. Thyroxine is produced by epithelial cells that make up round, colloid-

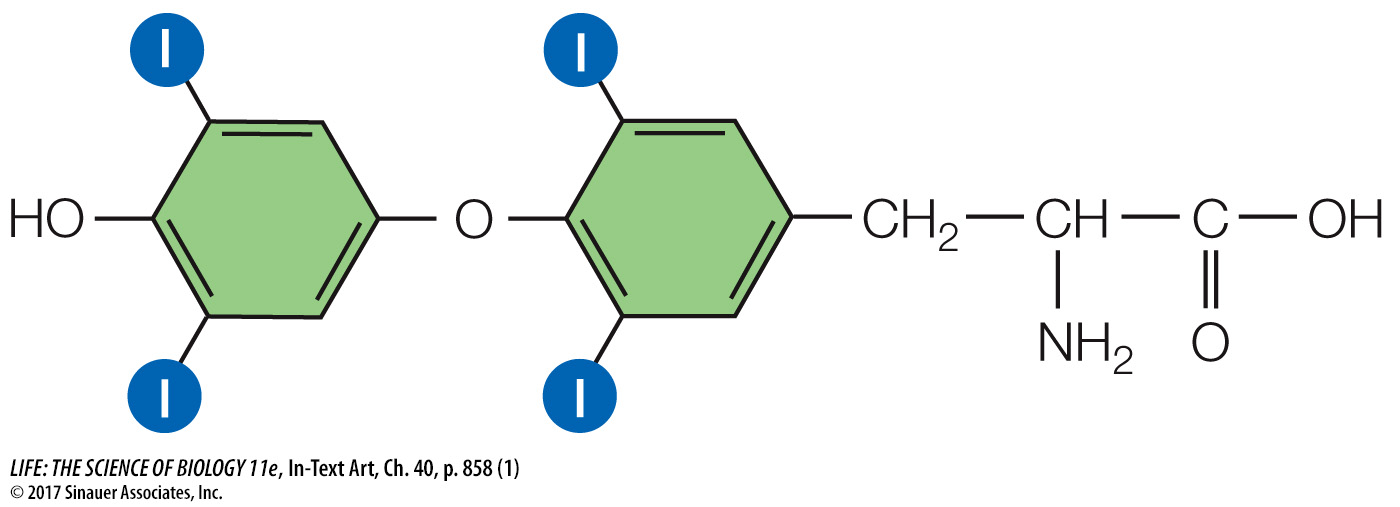

Thyroxine, a crucial signal in the regulation of cellular energy metabolism, begins as the glycoprotein thyroglobulin, which is synthesized by the follicle cells and packaged in secretory vesicles. The follicle cells actively take up iodide from the blood and move it into the lumen of the follicle (Figure 40.11B). Each thyroglobulin molecule contains about 100 tyrosine units. When the secretory vesicles release thyroglobulin into the lumen of the follicle, they also release an enzyme that catalyzes the iodination of the tyrosine units in the thyroglobulin. When the thyroid gland is stimulated to release thyroxine, the follicle cells take up thyroglobulin from the follicle by endocytosis. These bits of thyroglobulin are then cleaved to form smaller molecules consisting of only two tyrosine units, and these molecules leave the follicle cells and enter the blood. If these molecules are iodinated at the maximum of four sites on the tyrosine units, the hormone is tetraiodothyronine, or T4:

858

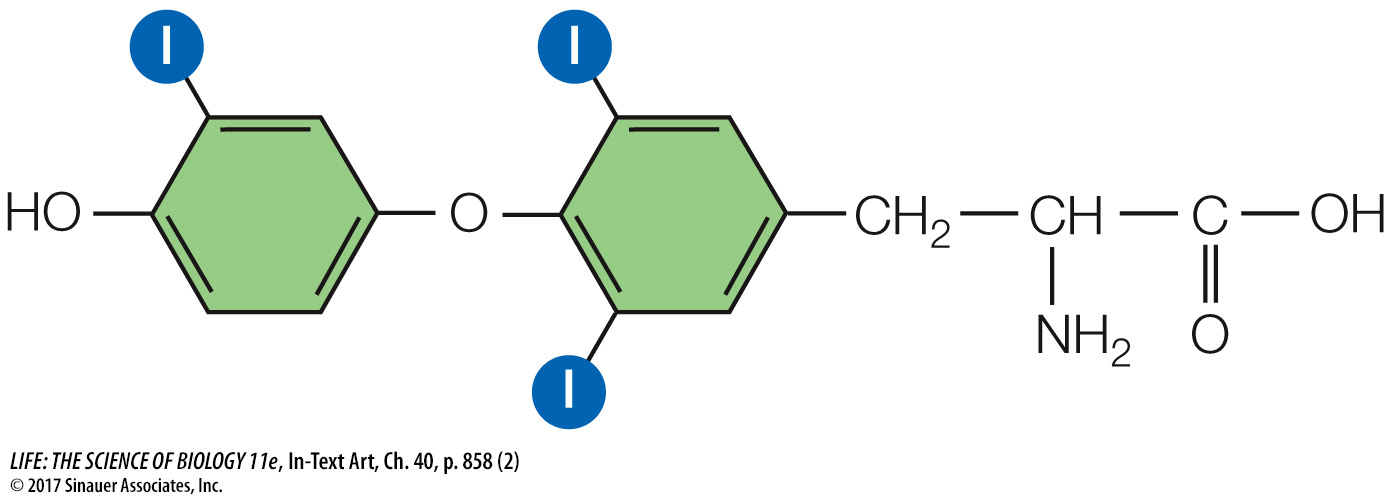

and if they are iodinated at only three sites, they are triiodothyronine, or T3:

The thyroid usually releases about ten times as much T4 as T3. However, T3 is a more active hormone than T4, so when you read about the effects of thyroxine, keep in mind that the actions discussed are primarily those of T3. The difference in the activities of T3 and T4 makes it possible to control the effects of thyroxine in different tissues. Within target cells, T4 can be converted to T3 by an enzyme called deiodinase. A different deiodinase can convert T4 into an inactive hormone called reverse T3. Deiodinase can also inactivate T3 by converting it into T2 or T1. Thus each target cell can set a unique sensitivity to thyroid hormones using these enzymes to control the conversion of T4 to T3 or to reverse T3.

TSH AND TRH REGULATE THYROXINE PRODUCTION The tropic hormone thyroid-

Because thyroxine is lipid-

During development and growth, thyroxine promotes amino acid uptake and protein synthesis. Insufficient thyroxine in a human fetus or growing child greatly retards physical and mental development, resulting in a condition known as cretinism.

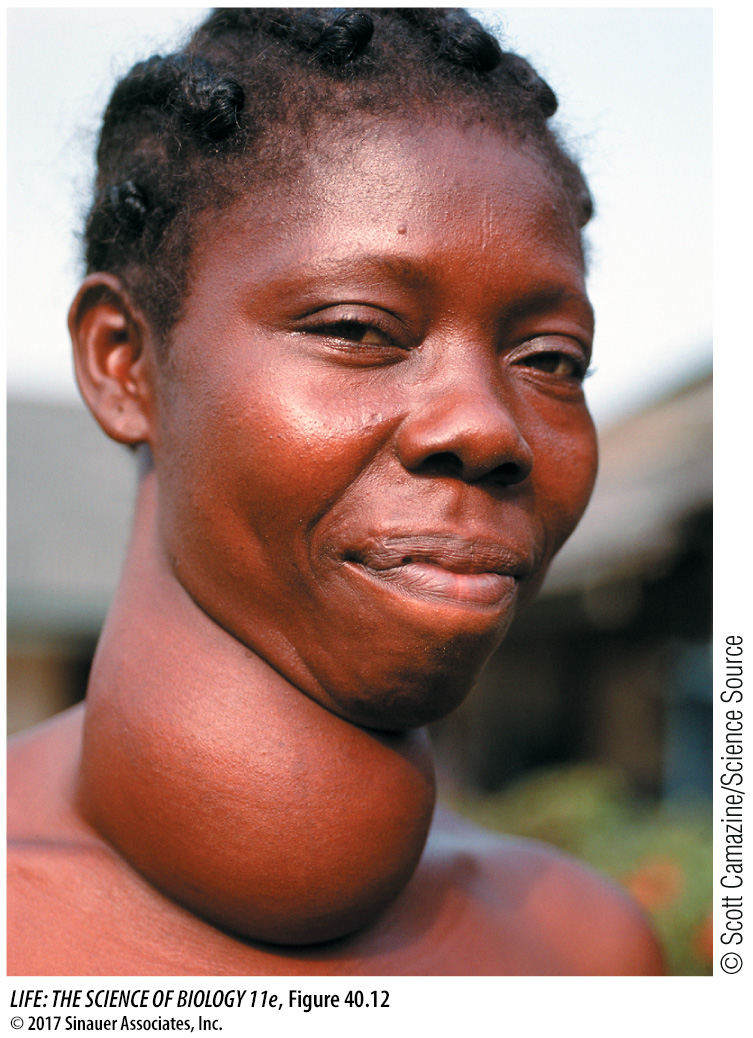

GOITER A goiter is an enlarged thyroid gland (Figure 40.12) that can be associated with either hyperthyroidism (excess production of thyroxine) or hypothyroidism (thyroxine deficiency). The negative feedback loop whereby thyroxine controls TSH release helps explain how two seemingly opposite conditions can result in the same symptom.

The most common cause of hyperthyroid goiter is Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disease involving an antibody to the TSH receptor. This antibody binds to and activates the TSH receptors on the follicle cells, causing uncontrolled production and release of thyroxine. Blood levels of TSH are low due to negative feedback from high levels of thyroxine, but the thyroid remains maximally stimulated and grows bigger. People with hyperthyroidism have high metabolic rates, usually feel hot, and may develop a buildup of fat behind the eyeballs that causes their eyes to bulge.

859

Hypothyroid goiter results when there is not enough circulating thyroxine to turn off TSH production. The most common cause is a deficiency of dietary iodide, without which the follicle cells cannot make thyroxine. Without sufficient thyroxine, TSH levels remain high and the thyroid continues to produce large amounts of thyroglobulin. Because sufficient iodine is not available, however, the thyroglobulin is poorly iodinated. When it is broken down by the follicle cells, it produces little functional T3 or T4. TSH levels remain high and stimulate more and more synthesis of thyroglobulin, and the thyroid gets bigger. The symptoms of hypothyroidism are low metabolism, intolerance of cold, and general physical and mental sluggishness.

Goiter affects about 5 percent of the world’s population. The addition of iodide to table salt has greatly reduced the incidence of hypothyroid goiter in industrialized nations, but the condition is still common in other parts of the world and is a leading cause of intellectual impairment.