Childbirth is triggered by hormonal and mechanical stimuli

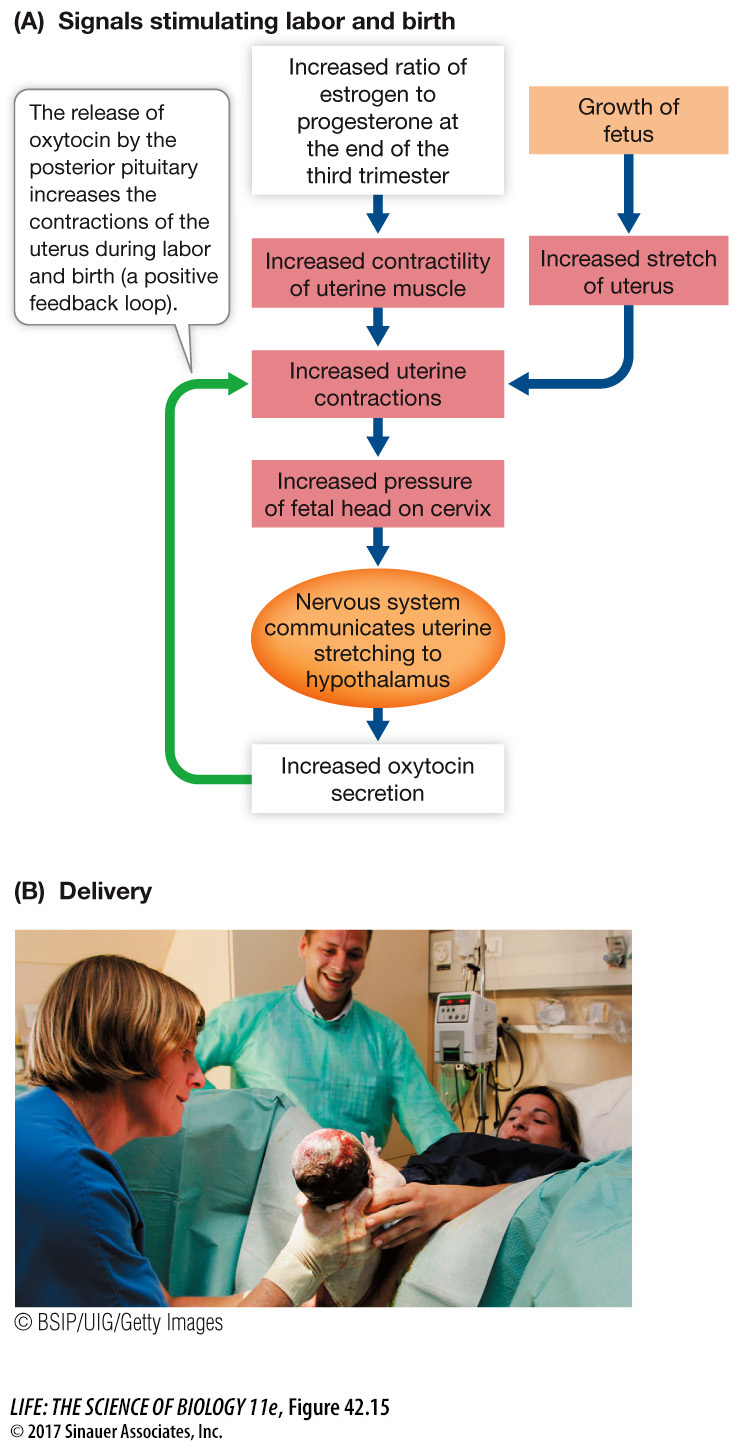

Throughout pregnancy, the muscles of the uterine wall periodically undergo slow, weak, rhythmic contractions called Braxton Hicks contractions. These contractions become stronger during the third trimester of pregnancy and are sometimes called false labor. The contractions of true labor mark the beginning of childbirth. Both hormonal and mechanical stimuli contribute to the onset of labor (Figure 42.15A).

Progesterone inhibits and estrogen stimulates contractions of uterine muscle. Toward the end of the third trimester, the estrogen–

Mechanical stimuli come from the stretching of the uterus by the fully grown fetus and the pressure of the fetal head on the cervix. These mechanical stimuli increase the release of oxytocin by the mother’s posterior pituitary, which in turn increases the activity of uterine muscle, causing even more pressure on the cervix. This positive feedback loop converts the weak, slow, rhythmic Braxton Hicks contractions into stronger labor contractions.

In the early stage of labor, hormonal changes and pressure created by the contractions cause the cervix to dilate (expand) until it is large enough to allow the baby to pass through. Gradually the contractions become more frequent and more intense. This stage of labor lasts an average of 12 to 15 hours in a first pregnancy, but is usually 8 hours or less in subsequent ones.

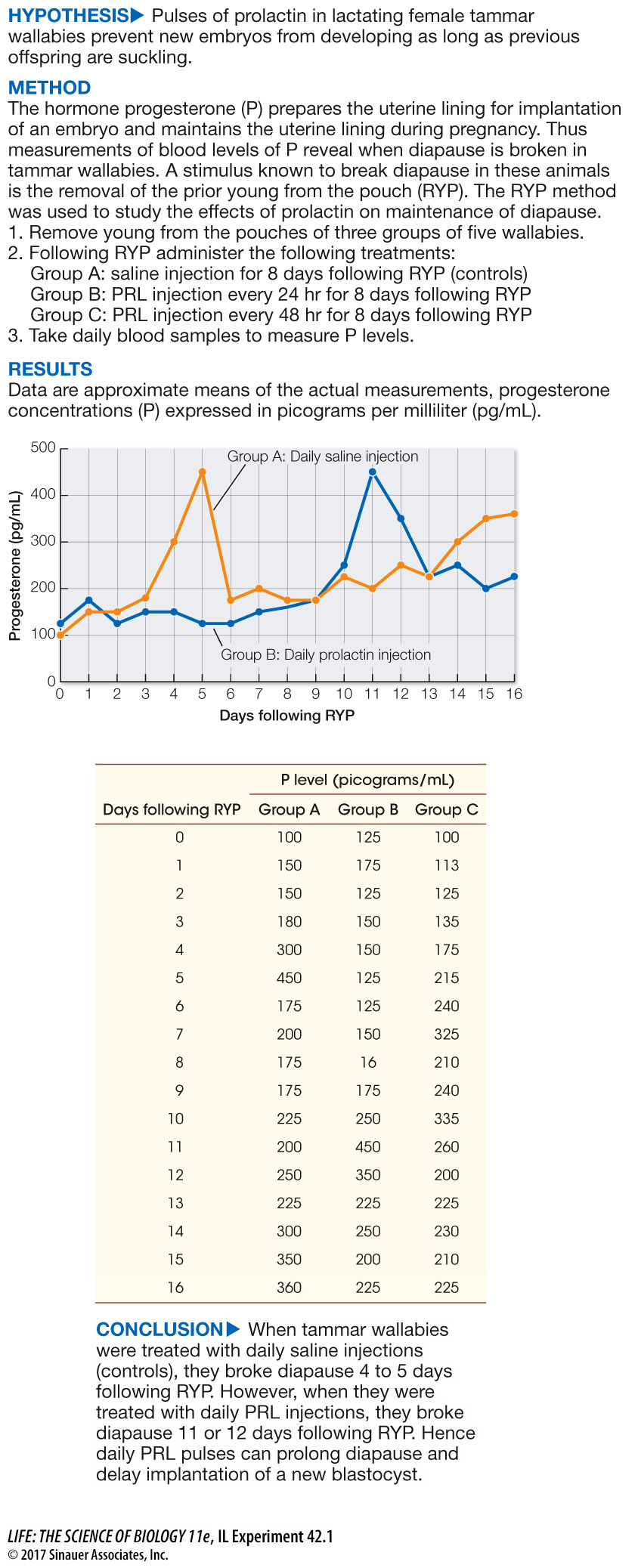

The second stage of labor begins when the cervix is fully dilated to a diameter of about 10 cm (Figure 42.15B). The baby’s head can now move into the vagina. Passage of the fetus through the vagina is assisted by the mother’s bearing down (“pushing”) with her abdominal and other muscles. Once the head and shoulders of the baby clear the cervix, the rest of its body eases out rapidly, but it is still connected to the placenta by the umbilical cord. Once the baby clears the birth canal, it starts breathing and is independent of its mother’s circulation. The umbilical cord may then be clamped and cut. The segment still attached to the baby dries up and sloughs off in a few days, leaving behind its distinctive signature, the belly button—

909

investigating life

The Control of Diapause in the Tammar Wallaby

experiment

Original Paper: Hinds, L. A. and C. H. Tyndale-

In Chapter 40 (see Figure 40.4) we discussed how the hormone prolactin (PRL) has evolved to serve many physiological processes in different vertebrate groups, but these various processes all have some connection to reproduction. Since prolactin is involved in controlling lactation in mammals, could prolactin be the signal in the tammar wallaby that maintains embryonic diapause as long as suckling continues?

work with the data

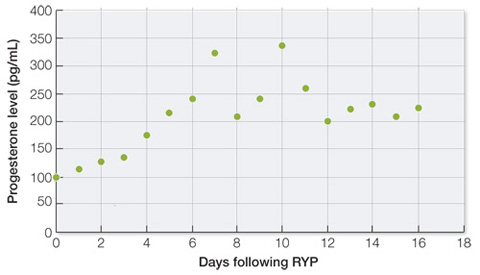

Following the experiment showing that daily pulses of PRL can maintain diapause, the investigators asked whether pulses of PRL every 2 days could maintain diapause. The data are shown in the table as Group C. Plotting the data will show if there is a difference in the response to PRL when pulses were given every other day following RYP.

QUESTIONS

Question 1

Plot the data as was done for Groups A and B. Was the 48-

The data for this group were mixed, with minor peaks in mean PRL for the group occurring on days 7 and 10, indicating that some of the wallabies had broken diapause over that period of time. These rises occurred later than measured in the saline-

A similar work with the data exercise may be assigned in LaunchPad.