Reproductive technologies help solve problems of infertility

About 15 percent of couples in the United States are infertile—that is, they can’t have children. The reasons for infertility are many, and are about equally distributed between men and women. Several technologies have been developed to overcome barriers to both conceiving and bearing a child. The simplest of these is artificial insemination, in which the physician places sperm in the woman’s reproductive tract. This technique is useful if the male’s sperm count is low, if his sperm lack motility, or if problems in the female’s reproductive tract prevent the normal movement of sperm up the oviducts. Artificial insemination is also widely used in the production of domesticated animals such as cattle.

Assisted reproductive technologies, or ARTs, involve procedures that remove unfertilized eggs from the ovary, combine them with sperm outside the body, and then place fertilized eggs or egg–sperm mixtures in the appropriate location in the woman’s reproductive tract for development to take place. The first successful ART was in vitro fertilization (IVF). In IVF the woman is treated with hormones that stimulate many follicles in her ovaries to mature. Eggs are collected from these follicles, and sperm are collected from the intended father. Eggs and sperm are combined in a culture medium outside the body, where fertilization takes place. The resulting embryos can be injected into the mother’s uterus in the blastocyst stage or kept frozen for implantation later. The first “test tube baby” resulting from IVF was born in England in 1978. Since then, millions of babies have resulted from this ART.

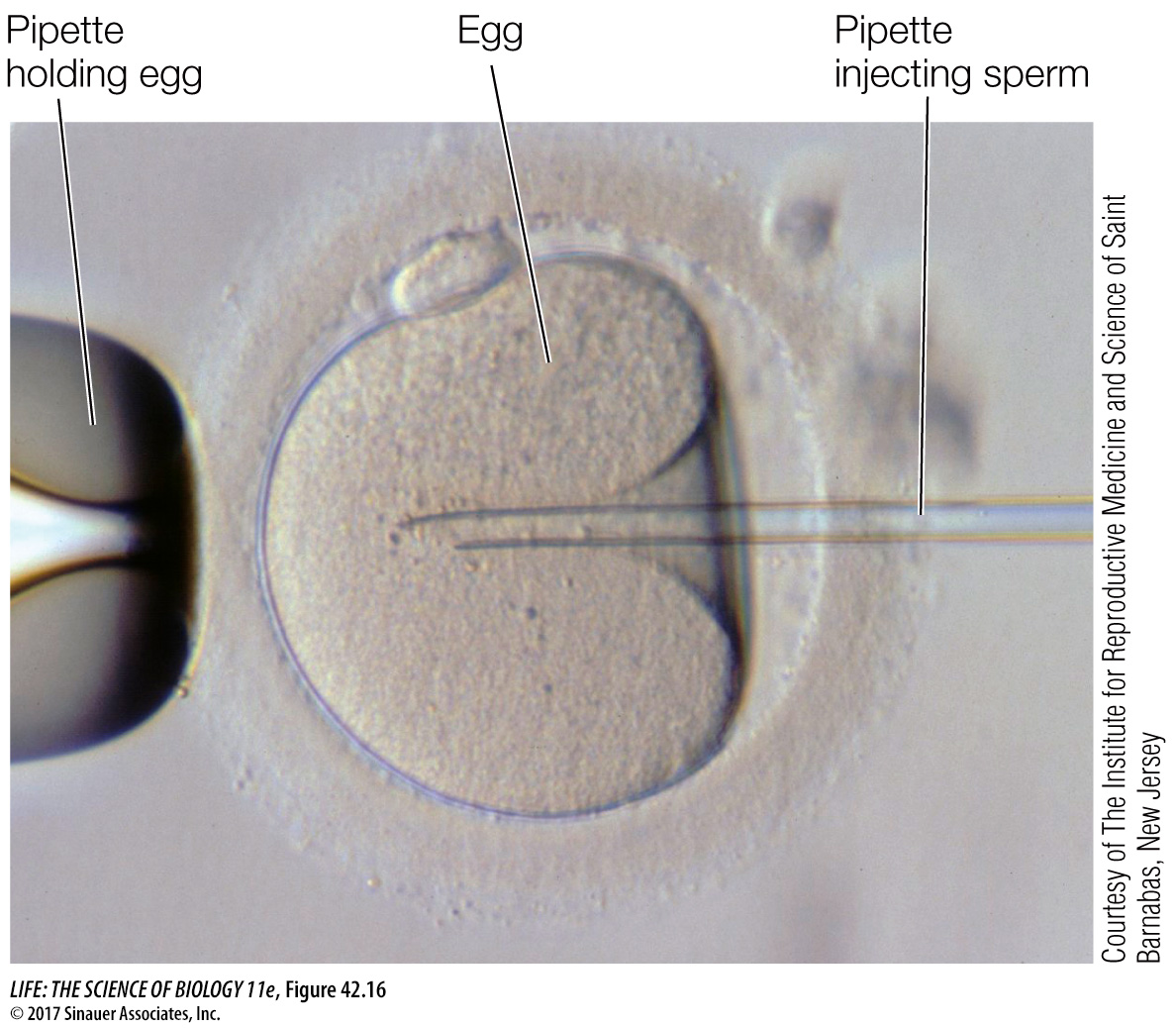

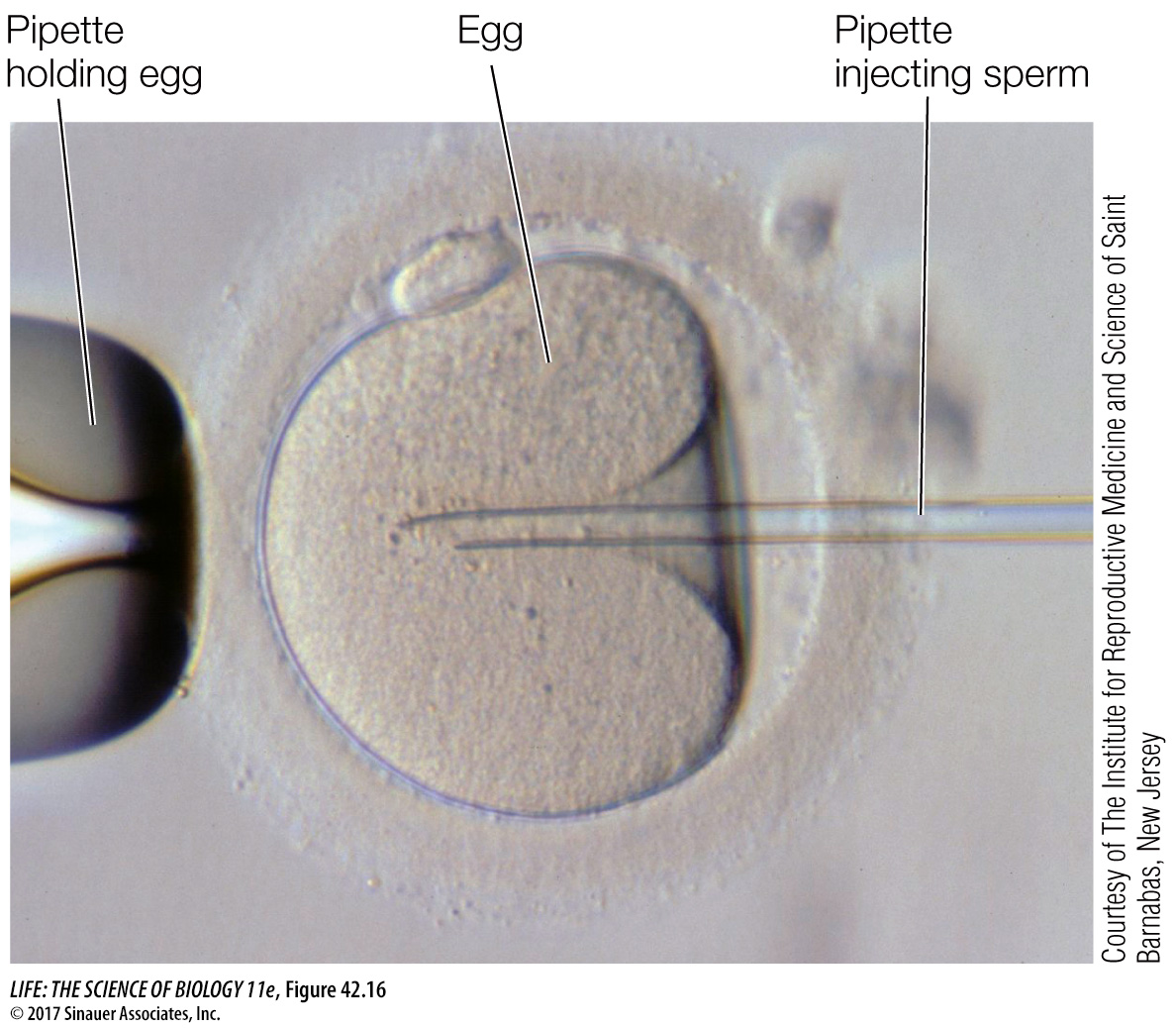

A major cause of IVF failure is failure of sperm to gain access to the egg cell membrane (see Figure 42.5). To solve this problem, methods have been developed to inject a sperm cell directly into the cytoplasm of an egg. In intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), an egg is held in place by suction applied through a polished glass pipette. A slender, sharp pipette is then used to penetrate the egg and inject a sperm (Figure 42.16). This ART was used successfully for the first time in 1992 by researchers in Belgium; now thousands of these procedures are performed in U.S. clinics each year, with a success rate of about 25 percent.

Figure 42.16 Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection In this procedure, a sperm is injected directly into a mature egg cell. The fertilized egg is then placed in the female reproductive tract, where it can implant and develop into a fetus.

IVF, coupled with techniques of genetic analysis, can eliminate the risk that adults who are carriers of genetic diseases will produce affected children. It is now possible to take a cell from a human embryo at the 4- or 8-cell stage (see Figure 43.3) without damaging its developmental potential. The sampled cell can be subjected to molecular analysis to determine whether it carries the harmful gene. This procedure, called preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), makes it possible to determine whether an embryo produced by IVF carries the genetic defect of concern.