Hox genes control differentiation along the anterior–

How is mesoderm in the anterior part of a mouse embryo programmed to produce forelegs rather than hind legs? In Key Concept 19.4, you saw how homeotic genes control body segmentation in Drosophila. You also learned that all homeotic genes contain a DNA sequence called the homeobox. In vertebrates, the homeotic genes that control differentiation along the anterior–

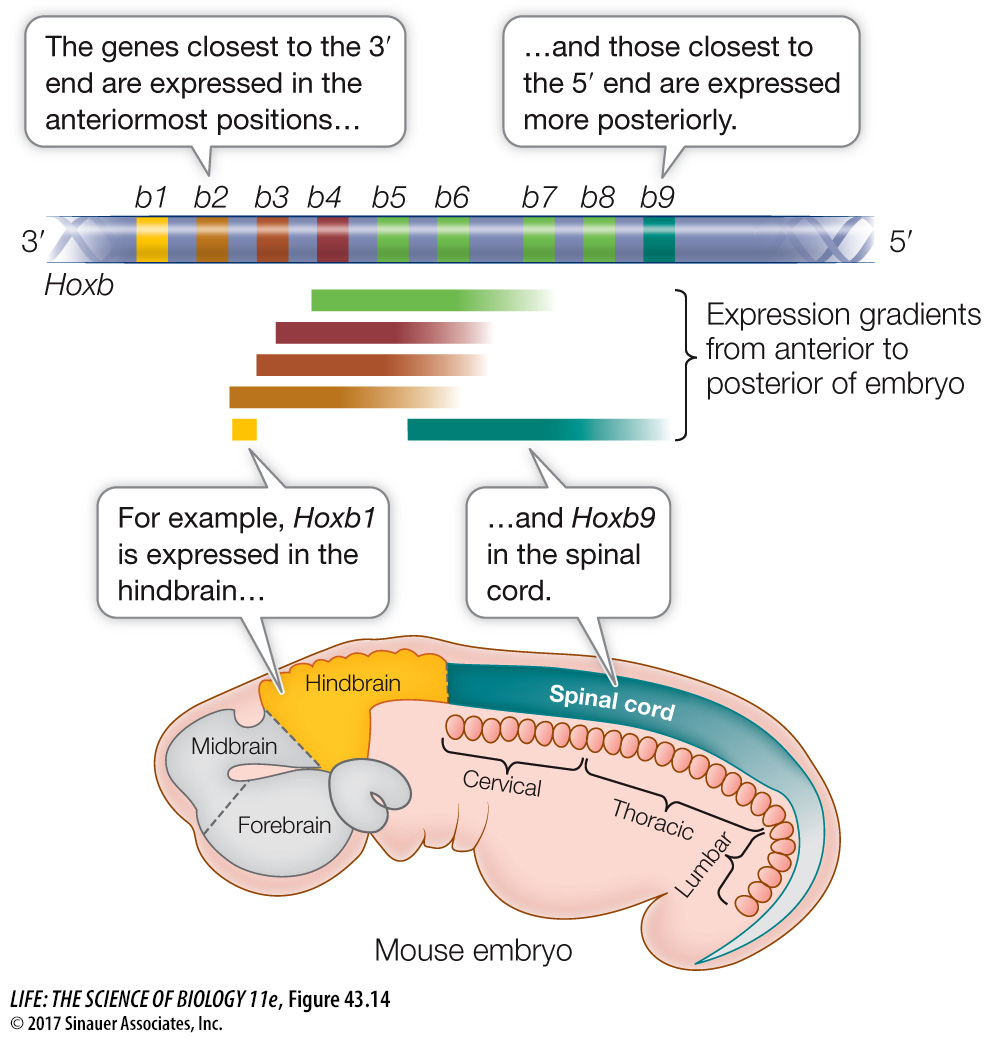

In mammals, four Hox gene complexes reside on different chromosomes in clusters of about ten genes each. Remarkably, the temporal and spatial expression of these genes generally follows the same pattern as their linear order on their chromosome. That is, the Hox genes closest to the 3′ end of each gene complex are expressed first and in the anterior of the embryo. The Hox genes at the 5′ end of the gene complex are expressed later and in a more posterior part of the embryo. As a result, different segments of the embryo receive different combinations of Hox gene products, which serve as transcription factors (Figure 43.14; see also Figure 19.15).

932

Whereas Hox genes give cells information about their position on the anterior–

After body segmentation develops, the formation of organs and organ systems progresses rapidly. The development of an organ involves extensive inductive interactions. An example is the ability of the chordamesoderm to induce overlying ectoderm to become neural ectoderm, and form the neural tube (see Figure 43.12). These inductive interactions are a current focus of study for developmental biologists.