Chapter Introduction

960

45

key concepts

45.1

Sensory Receptor Cells Convert Stimuli into Action Potentials

45.2

Chemoreceptors Respond to Specific Molecules

45.3

Mechanoreceptors Respond to Physical Forces

45.4

Photoreceptors Respond to Light

Sensory Systems

investigating life

Seeing in the Dark

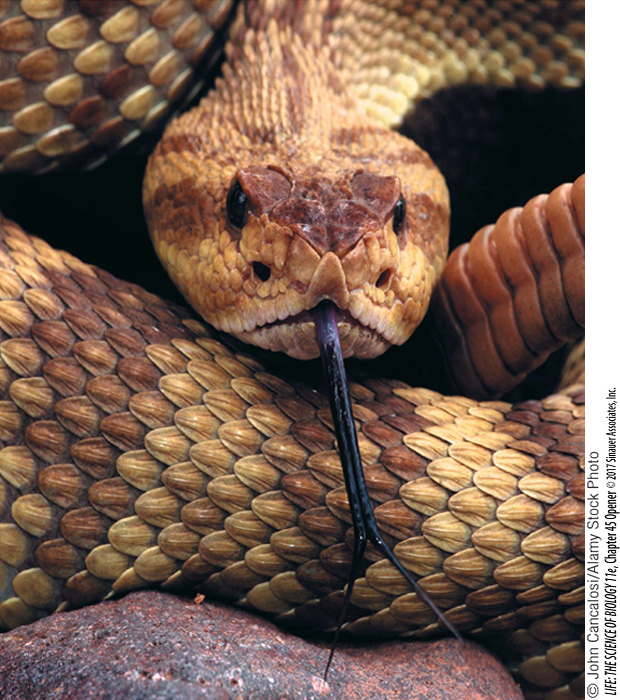

A rattlesnake can see to strike a running rodent in complete darkness. How can this be, when “seeing” means using the eyes to detect light waves, and “complete darkness” means no light? It is possible because these definitions are based on human capabilities. What we call “light” is actually only a small portion (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet) of the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation. Other animals see wavelengths humans cannot. Some insects, for example, perceive patterns on flowers that reflect ultraviolet wavelengths invisible to humans (see Figure 28.15). Similarly, rattlesnakes “see” infrared wavelengths that we cannot (although at high enough levels of intensity, humans feel infrared wavelengths as heat).

It is not the snake’s eyes that perceive infrared light. Pit vipers, rattlesnakes, and their relatives have pit organs located between the nostril and the eye on each side of the skull that contain high densities of infrared-

Our definition of silence is as human-

“Reality” is what our eyes see, our ears hear, our noses smell, and what we touch and taste. Humans sense only a limited range of the information available. Animals with different ranges of sensitivity process different sources of information and perceive the world quite differently than we do. A challenge for neurobiologists is to understand how neurons are adapted to detect different types of information in the environment.

How do pit vipers “see” in the dark?