Gustation is the sense of taste

In humans and other vertebrates, the sense of taste, gustation, depends on clusters of chemoreceptors called taste buds. The taste buds of terrestrial vertebrates are confined to the mouth cavity, but some fish have taste buds in the skin that enhance their ability to sense their environment. Some fish living in murky water are very sensitive to small amounts of amino acids in the water and can find food without the use of vision. The duck-

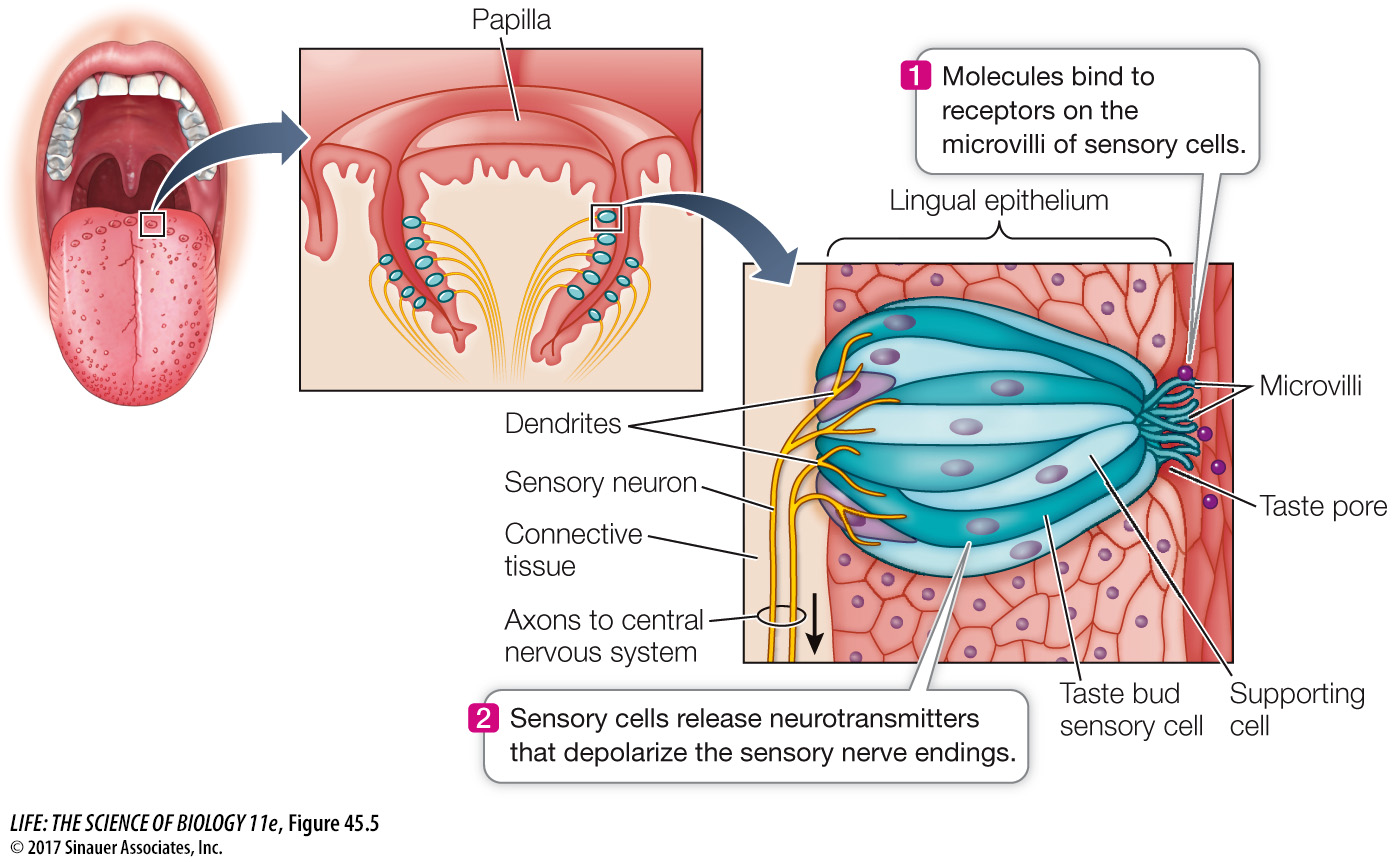

The human tongue has 5,000–

The tongue does a lot of hard work, so its epithelium, along with cells of its taste buds, are shed and replaced at a rapid rate. Individual taste bud cells last about 10 days before they are replaced, but the sensory neurons associated with them live on, constantly forming new synapses as new taste buds form.

Gustation begins with the membrane receptor proteins of the microvilli of the taste bud sensory cells (see Figure 45.5). Humans perceive five taste classes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. However, taste buds can distinguish among a variety of sweet-

Various selective pressures led to the evolution of diversity in gustatory receptors. Receptors for bitter tastes may have evolved as protective mechanisms enabling animals to detect toxic plant compounds such as quinine, caffeine, and nicotine. Because many such toxic compounds evolved in plants as protections against herbivorous predators, having a variety of receptors in those herbivores is a product of the continuous “arms race” between predators and prey (see Key Concept 55.1). Also, a large number of molecules in food could indicate nutritional value, so a variety of receptors is of value. The diversity of sweet receptors helps explain why it has been possible to invent many chemically distinct artificial sweeteners.

Regardless of the mechanism of taste transduction by the receptors of the taste buds, all these cells release neurotransmitter onto sensory neurons. These neurons then generate action potentials that are conducted to the CNS, where they are interpreted as specific taste sensations. The full complexity of the chemosensitivity that enables us to enjoy the subtle flavors of food comes from the combined activation of gustatory and olfactory receptors, which is why you may lose your sense of taste when you have a cold.