Olfaction is the sense of smell

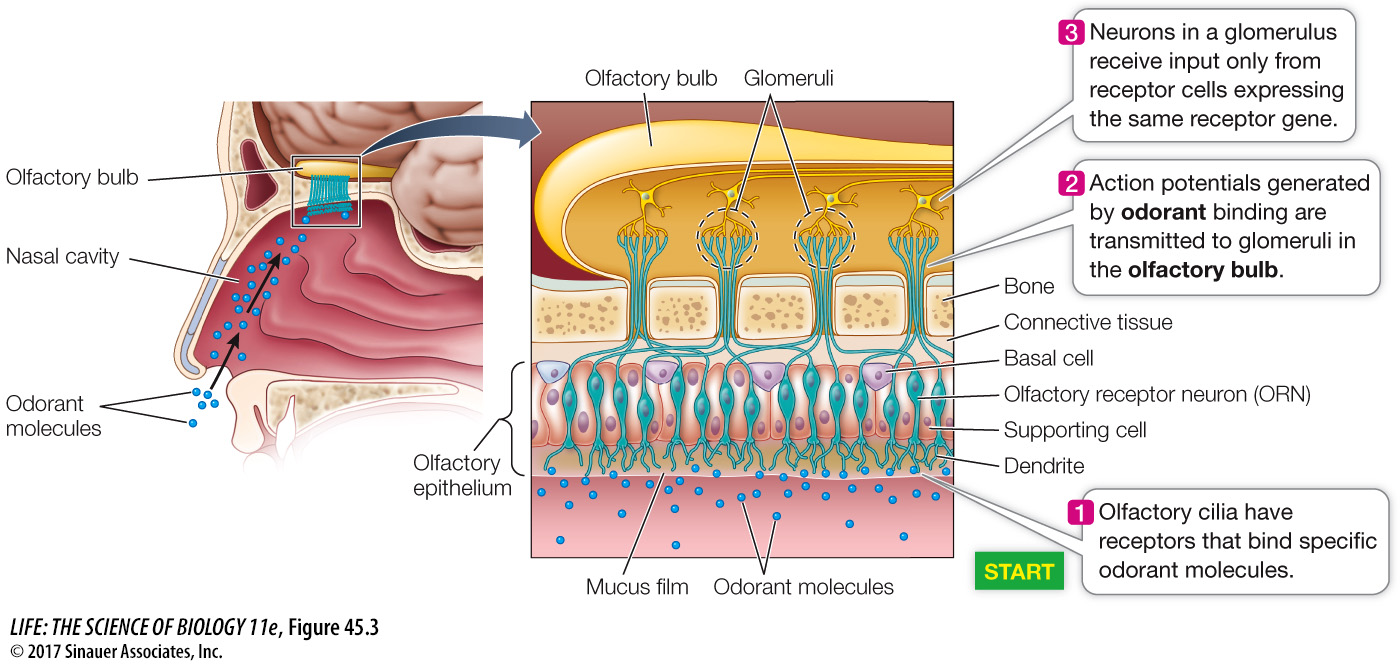

The sense of smell, olfaction, depends on chemoreceptors. In vertebrates the olfactory receptors are neurons embedded in a layer of epithelial tissue in the uppermost region of the nasal cavity (Figure 45.3). The dendrites of these neurons project as olfactory cilia on the surface of the nasal epithelium, and their axons extend through holes in the overlying bone into the olfactory bulb (the olfactory integration area of the brain). A protective layer of mucus covers the nasal cavity epithelium. Molecules from the environment must diffuse through this mucus to reach the receptor proteins on the olfactory cilia. When you have a cold, the amount of mucus in your nose increases, and the epithelium swells. With this in mind, you can easily understand why respiratory infections can cause you to lose your sense of smell.

An odorant is a molecule in the environment that binds to and activates an olfactory receptor protein on the cilia of olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs). Different olfactory receptor proteins bind specific subsets of odorant molecules. An odorant molecule binding to its receptor on an ORN activates a *G protein. The G protein then activates an enzyme that causes an increase of a second messenger (cAMP in vertebrates) in the cytoplasm. The second messenger binds to and opens cation channels in the ORN’s cell membrane, causing an influx of Na+ into the ORN—

965

*connect the concepts Key Concept 7.2 describes how G protein-

The olfactory world has an enormous number of odors and a correspondingly large number of olfactory receptor proteins. In the 1990s Linda Buck and Richard Axel discovered a family of about 1,000 genes in mice (about 3 percent of the mouse genome) that code for olfactory receptor proteins. Each receptor protein that is expressed is found in a limited number of ORNs in the olfactory epithelium, and each ORN expresses just one receptor type. The investigators matched specific gene products with the odorants they detect. For their discoveries of the molecular nature of the olfactory system, Buck and Axel received a Nobel Prize in 2004.

Olfactory sensitivity enables discrimination of many more odorants than there are olfactory receptors. An odorant molecule can be quite complex, and different regions of that molecule may bind to different receptor proteins. The next stage of processing olfactory information is in the olfactory bulb, where axons from ORNs expressing the same receptor protein cluster together on olfactory bulb neurons, forming structures called glomeruli (see Figure 45.3). A complex odorant molecule can activate a unique combination of glomeruli in the olfactory bulb, so an olfactory system with hundreds of different receptor proteins can discriminate an astronomically large number of smells. The more odorant molecules that bind to ORNs, the greater the frequency of action potentials and thus the greater the intensity of the perceived smell.

Humans have a sensitive olfactory system, but in comparison with most mammals we depend far more on vision than on olfaction. The nasal epithelium of a typical dog is 15–