Language abilities are localized in the left cerebral hemisphere

No aspect of brain function is as integrally related to human consciousness and intellect as language. Therefore brain mechanisms that underlie the acquisition and use of language are extremely interesting to neuroscientists. A curious observation about language ability is that it resides in one cerebral hemisphere—

Fascinating research on this subject was conducted by Roger Sperry and his colleagues at the California Institute of Technology. The two cerebral hemispheres are connected by a tract of white matter called the corpus callosum. In one severe form of epilepsy, bursts of action potentials causing seizures travel between hemispheres via the corpus callosum. Cutting the tract eliminates the problem, and patients function well following surgery. However, these “split-

996

After the surgery, if an object is shown in the right visual field and the left eye is closed (see Figure 46.10), the patient can describe it verbally and in writing. If the object is shown in the left visual field and the right eye is closed, the patient cannot describe it either verbally or in writing, but can use his or her left hand to point to a picture of the object. Without the connecting tissue between the two hemispheres, knowledge or experience of the right hemisphere can no longer be expressed in language.

Individuals who have suffered damage to the left hemisphere frequently suffer from some form of aphasia, a deficit in the ability to use or understand words. Studies of such individuals have identified several language areas in the left hemisphere.

Broca’s area, located in the frontal lobe just in front of the primary motor cortex, is essential for speech. Damage to Broca’s area results in halting, slow, poorly articulated speech or even complete loss of speech, but the patient can still read and understand language.

Wernicke’s area, located in the temporal lobe close to its border with the occipital lobe, is more involved with sensory than with motor aspects of language. Damage to Wernicke’s area can cause a person to lose the ability to speak sensibly while retaining the abilities to form the sounds of normal speech and to imitate its cadence. Such a patient cannot understand spoken or written language.

The angular gyrus, located near Wernicke’s area, is involved in integrating spoken and written language.

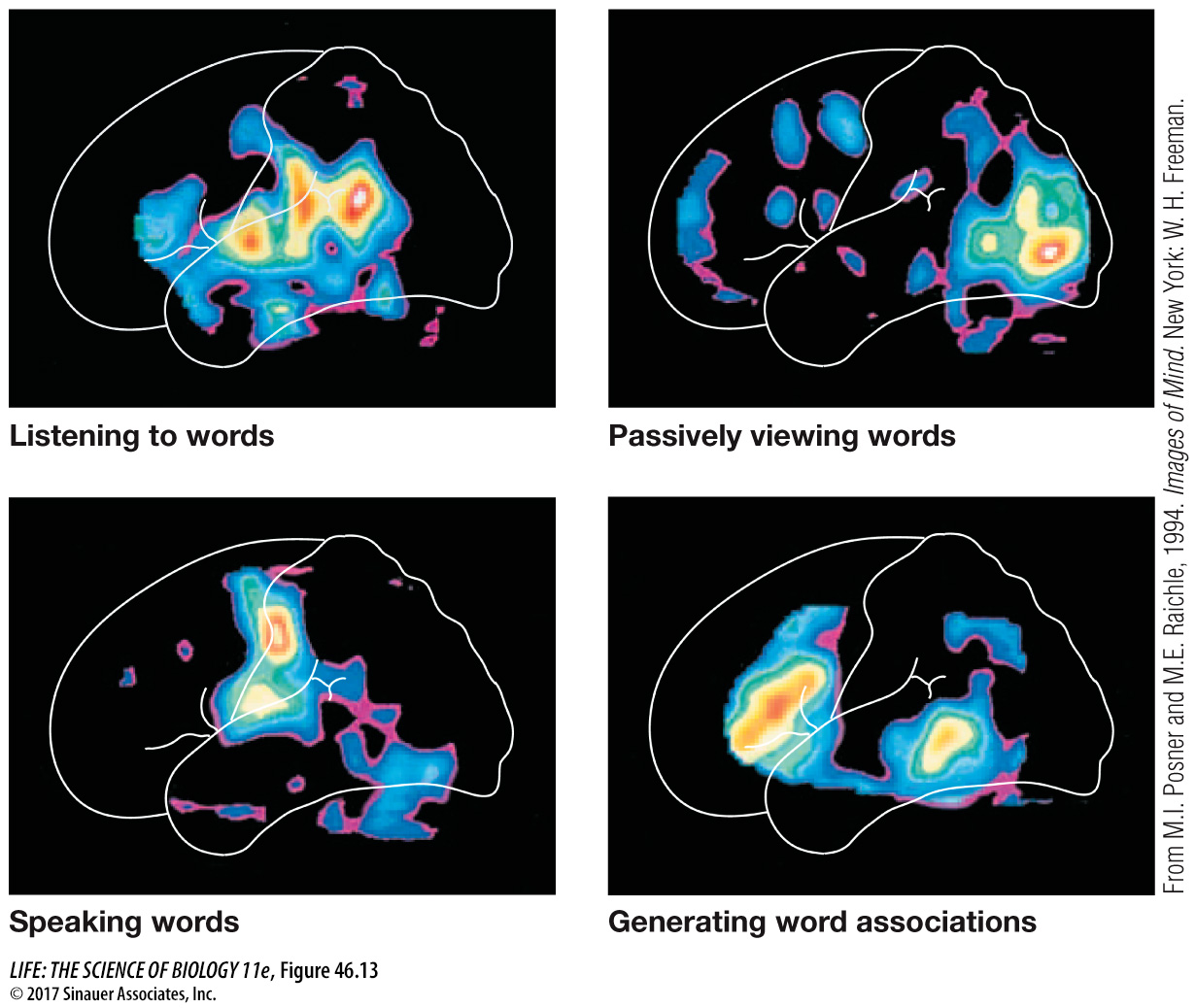

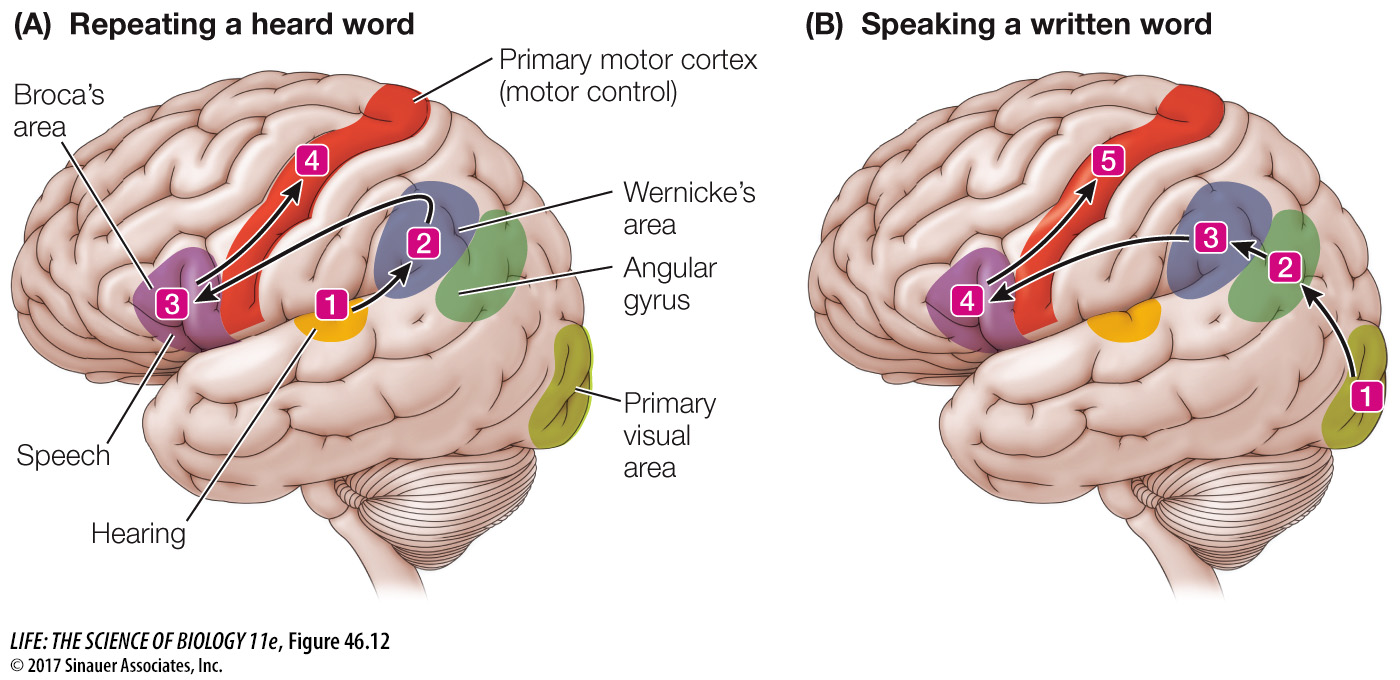

Normal language ability depends on the flow of information among various areas of the left cerebral cortex. Input from spoken language travels from the auditory cortex to Wernicke’s area (Figure 46.12A). Input from written language travels from the visual cortex to the angular gyrus to Wernicke’s area (Figure 46.12B). Commands to speak are formulated in Wernicke’s area and travel to Broca’s area and from there to the primary motor cortex. Damage to any one of those areas or the pathways between them can result in aphasia. Using modern methods of brain imaging such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or positron emission tomography (PET), it is possible to see the metabolic activity in different brain areas when the brain is using language (Figure 46.13).

Activity 46.3 Language Areas of the Cortex

www.life11e.com/