The strength of a muscle contraction depends on how many fibers are contracting and at what rate

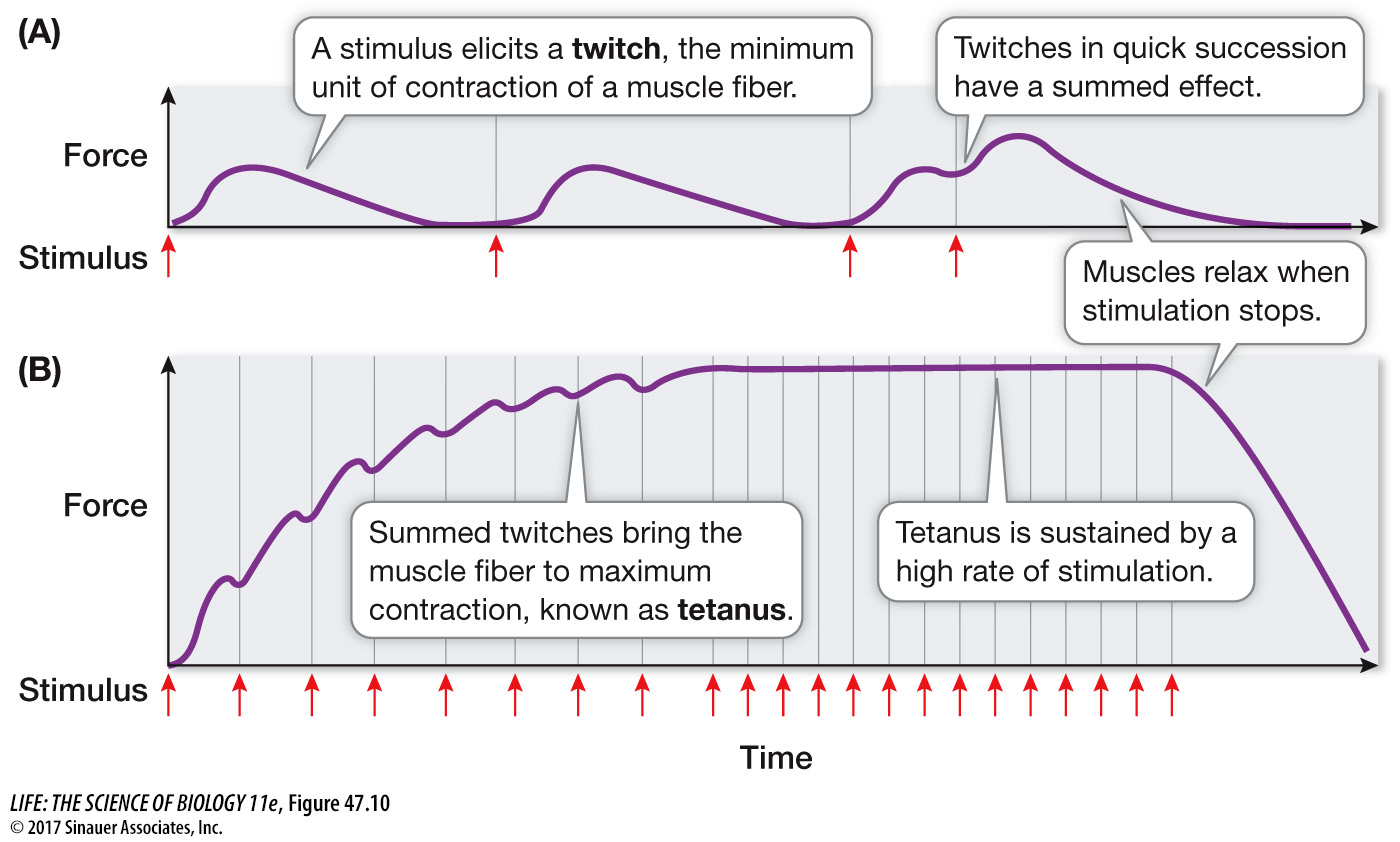

In skeletal muscle, the arrival of an action potential at a neuromuscular junction causes an action potential in a muscle fiber. The spread of that action potential through the muscle fiber’s T tubule system causes a minimum unit of contraction, called a twitch. A twitch can be measured in terms of the tension, or force, it generates (Figure 47.10A). A single action potential stimulates a single twitch, but the ultimate force generated by an action potential varies enormously depending on how many muscle fibers it reaches. The level of tension an entire muscle generates depends on two factors: the number of motor units activated, and the frequency at which the motor units fire.

In muscles responsible for fine movements, such as those of the fingers, a motor neuron may innervate only one or a few muscle fibers, but in a muscle that produces large forces, such as the biceps, a motor neuron innervates a large number of muscle fibers.

At the level of a muscle fiber, a single action potential stimulates a single twitch. If action potentials reaching the muscle fiber are adequately separated in time, each twitch is a discrete, all-

Twitches sum at high levels of stimulation because the calcium pumps in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (see Figure 47.5) are unable to clear the Ca2+ ions from the sarcoplasm between action potentials. Eventually a stimulation frequency can be reached that results in the continuous presence of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasm at high enough levels to cause continuous activation of the contractile machinery—

How long a muscle fiber can maintain a tetanic contraction depends on its supply of ATP. Eventually the contracting fiber will become fatigued and be unable to sustain the contraction. It may seem paradoxical that the lack of ATP causes fatigue, since the action of ATP is to break actin–

Many muscles of the body maintain a low level of tension even when the body is at rest. For example, the muscles of the neck, trunk, and limbs that maintain our posture against the pull of gravity are always working, even when we are standing or sitting still. Muscle tone comes from the activity of a small but changing number of motor units in a muscle; at any one time, some of the muscle’s fibers are contracting and others are relaxed. The nervous system is constantly readjusting muscle tone.