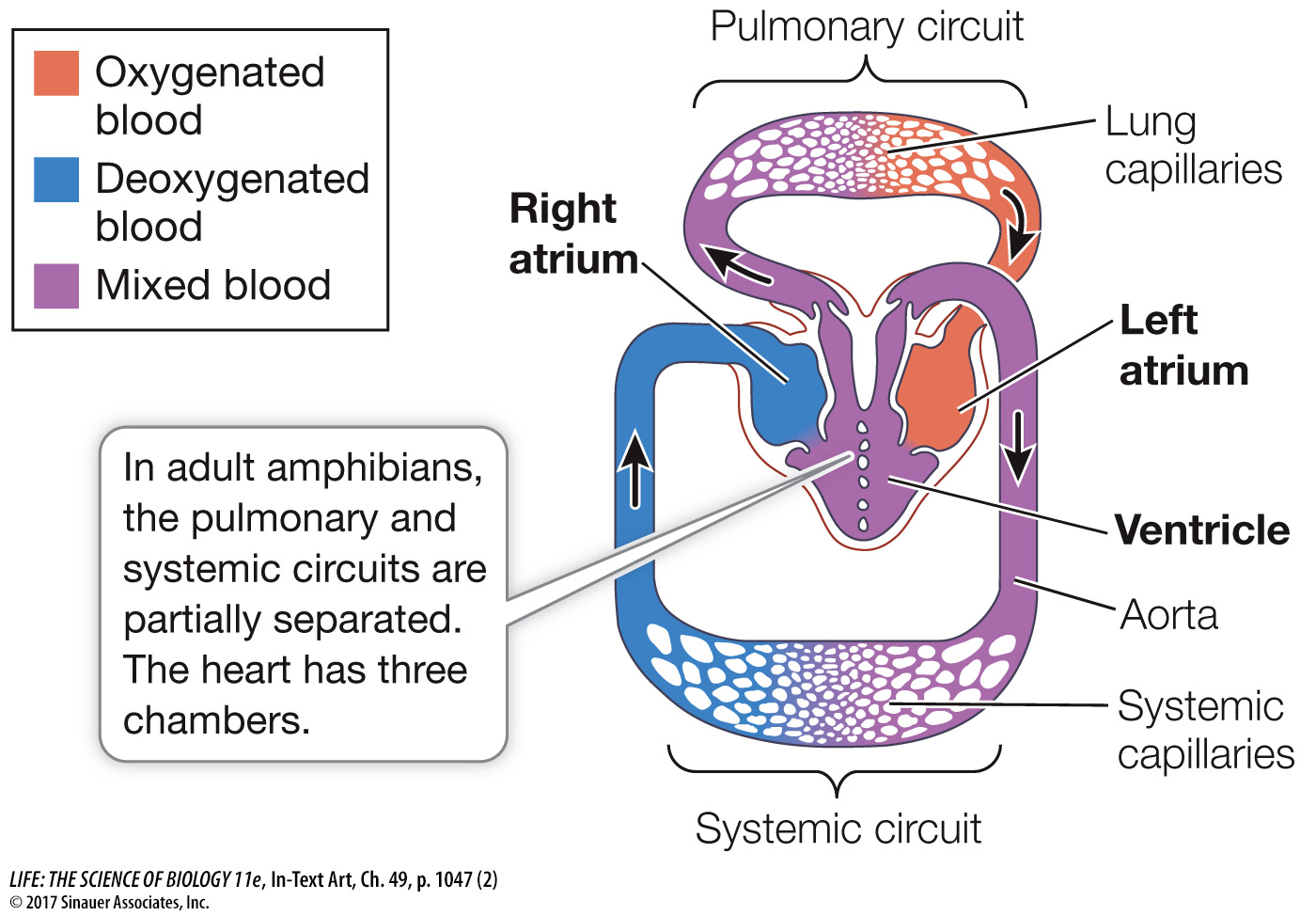

Amphibians have partial separation of systemic and pulmonary circulation

In adult amphibians, a single ventricle pumps blood to the lungs and the rest of the body, but two atria receive blood returning to the heart. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs, and the right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the body.

Because both atria deliver blood to the same ventricle, the oxygenated and deoxygenated blood could mix, in which case blood going to the tissues would not carry a full load of oxygen. Mixing is limited, however, because anatomical features of the ventricle direct the flow of deoxygenated blood from the right atrium primarily to the pulmonary circuit and the flow of oxygenated blood from the left atrium primarily to the aorta. Partial separation of pulmonary and systemic circulation has the advantage of allowing blood destined for the tissues to sidestep the large pressure drop that occurs in the gas exchange organ. Blood leaving the amphibian heart for the tissues moves directly to the aorta, and hence to the body, at a higher pressure than if it had first flowed through the lungs as it does in the fishes.

Amphibians have another adaptation for oxygenating their blood: they can pick up a considerable amount of oxygen in blood flowing through small blood vessels in their skin.