Blood flows back to the heart through veins

The pressure of the blood flowing from capillaries to venules is low and insufficient to propel blood back to the heart. The walls of veins are more expandable than the walls of arteries, and blood tends to accumulate in veins. As much as 60 percent of your total blood volume may be in your veins when you are resting. Because of their high capacity to stretch and store blood, veins are called capacitance vessels.

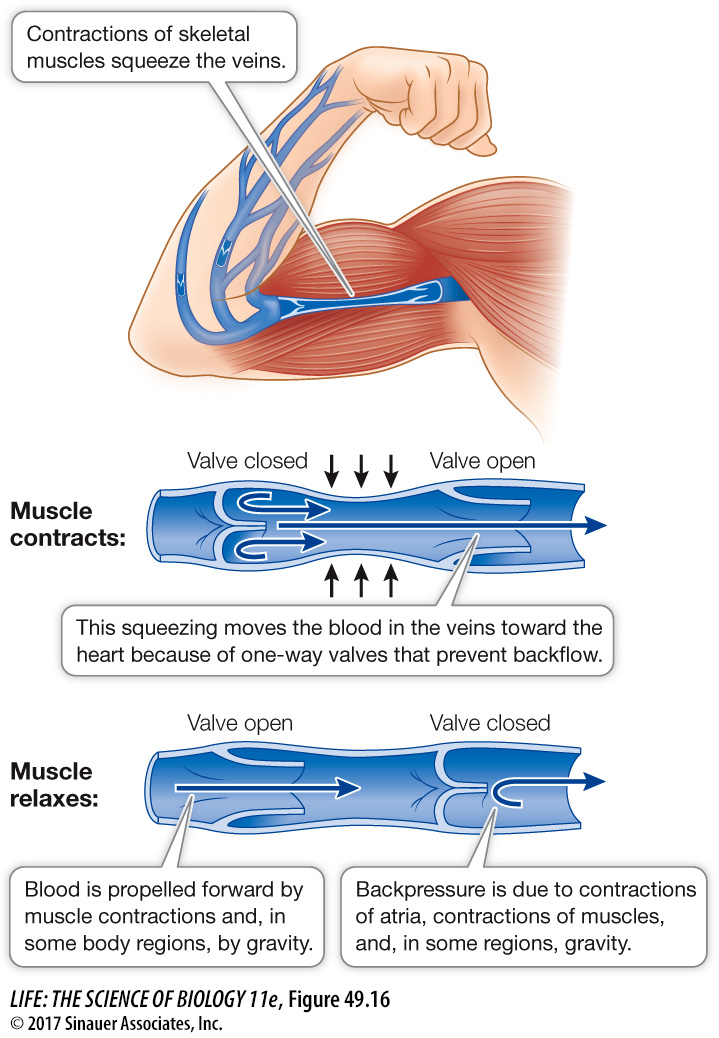

Blood flow through veins that are above the level of the heart is assisted by gravity. Below the level of the heart, however, venous return is against gravity. The most important force propelling blood from these regions is the squeezing of the veins by the contractions of surrounding skeletal muscles. As muscles contract, the veins are compressed and blood is squeezed through them. Blood flow may be temporarily obstructed during a prolonged muscle contraction, but when muscles relax, blood is free to move again. One-

In a resting person, gravity causes blood accumulation in the veins of the lower body and exerts backpressure on the capillary beds. This backpressure shifts the balance between blood hydrostatic pressure and osmotic pressure, causing increased loss of fluid to the intercellular spaces. That is why your feet swell during a long airline flight.

Because of the one-

The actions of breathing also help return venous blood to the heart. The muscles involved in inhalation create negative pressure that pulls air into the lungs (see Figure 48.11), and this negative pressure also pulls blood toward the chest, increasing venous return to the right atrium. In addition, some of the largest veins closest to the heart contain smooth muscle that contracts at the onset of exercise. Contraction of veins can rapidly increase venous return and stimulate the heart in accord with the Frank–