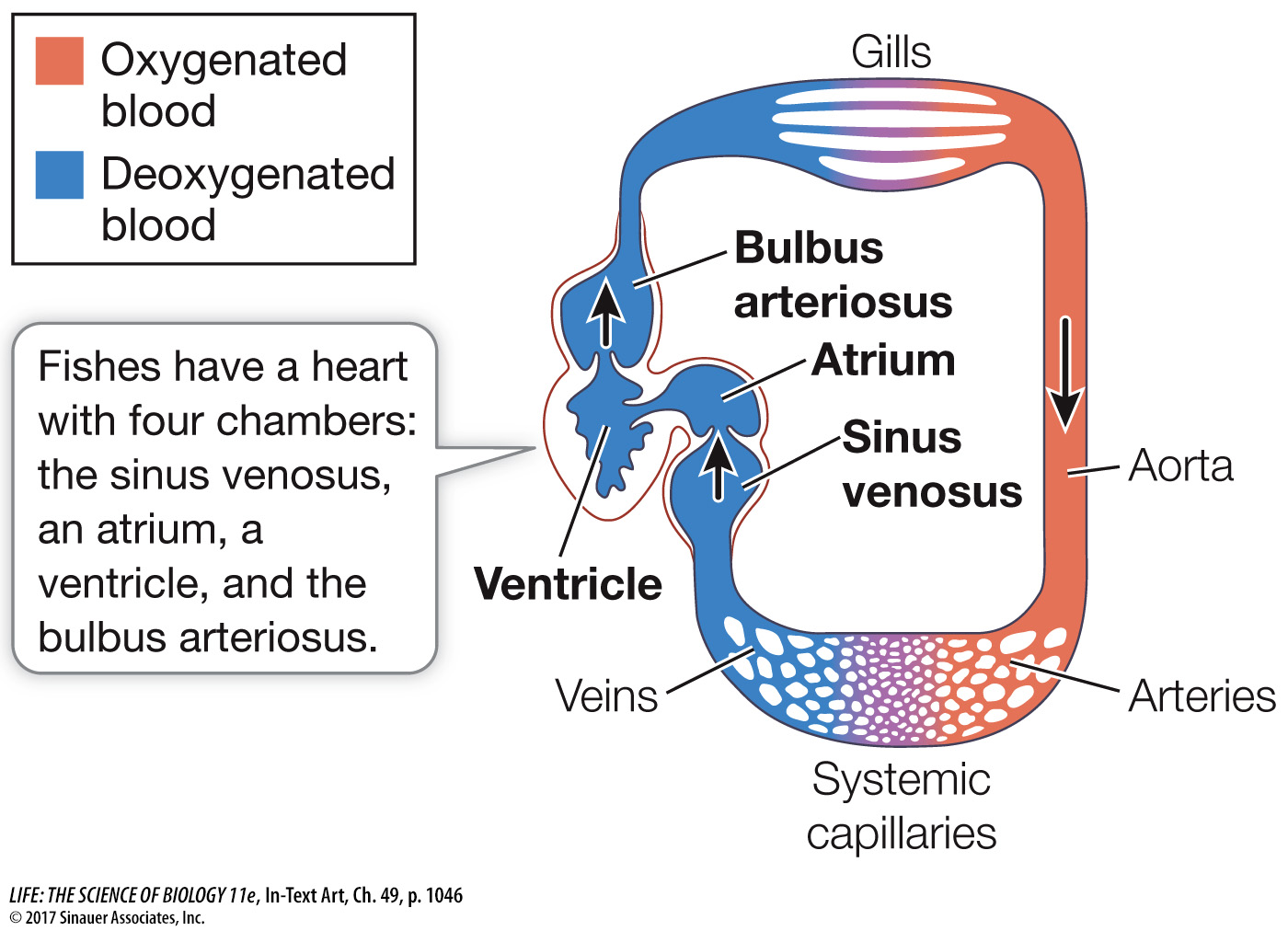

Circulation in fishes is a single circuit

The fish heart has four chambers that are connected in series. Blood returning from all parts of the body collects in a sinus venosus that feeds into the muscular atrium. The atrium pumps blood into the more muscular chamber, the ventricle. Contraction of the ventricle pushes blood into the last chamber, the bulbus arteriosus, a highly elastic chamber. The pressure imparted to the blood by the ventricle stretches the bulbus arteriosus, and its elastic recoil dampens the blood pressure oscillations generated by the beating of the heart. The arterial blood leaving the bulbus arteriosus under pressure flows through the gills, where respiratory gases are exchanged. Blood leaving the gills collects in a large dorsal artery, the aorta, which distributes blood to smaller arteries and arterioles leading to all the organs and tissues of the body. In the tissues, blood flows through beds of tiny capillaries, collects in venules and veins, and eventually returns to the sinus venosus of the heart. The unidirectional flow of blood in this circuit is enabled by one-

Most of the pressure imparted to the blood by the contraction of the ventricle is dissipated as a result of resistance to flow in the many narrow spaces in the gill lamellae (see Figure 48.5). Therefore blood leaving the gills and entering the aorta is under low pressure, limiting the capacity of the fish circulatory system to supply the tissues with oxygen and nutrients. Yet this limitation on arterial blood pressure does not seem to limit swimming performance. Some species, such as tuna and marlin, can swim at remarkably high rates of speed for long distances.

The evolutionary transition from breathing water to breathing air had important consequences for the vertebrate circulatory system. An example of how the system changed to serve a primitive lung can be seen in the African lungfishes.