Tubular guts have an opening at each end

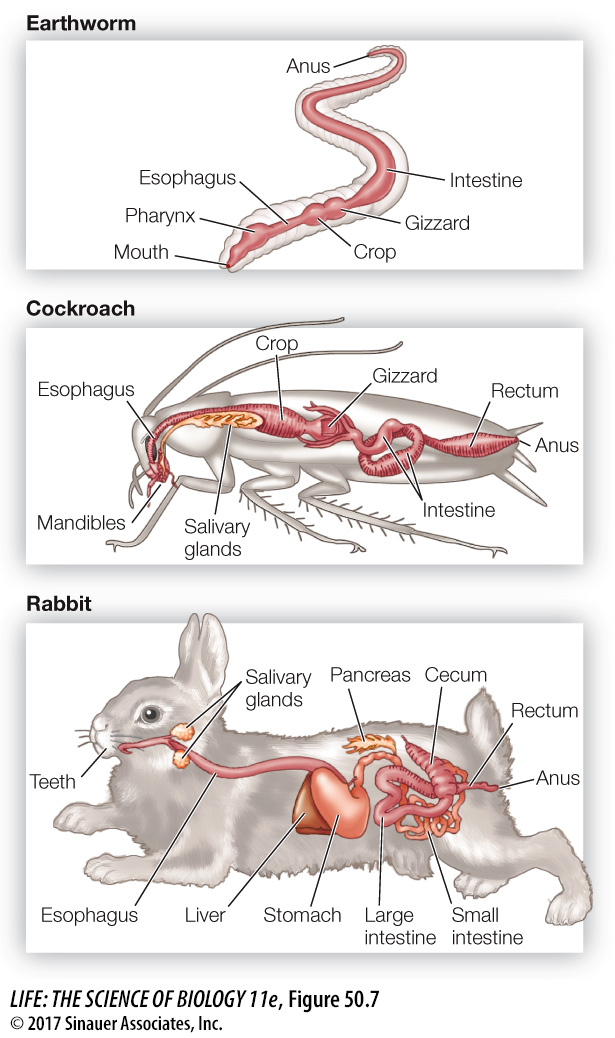

Animals classified as bilaterians (see Key Concept 30.1) have a tubular digestive system called a gastrointestinal system or more simply gut. The gut begins with a mouth that takes in food. The food is moved through the length of the gut as it is sequentially disassembled or digested, and the smallest units of the digested food are absorbed across the gut wall. Solid digestive wastes are eliminated through an anus. Different regions in the tubular gut are specialized for particular functions (Figure 50.7). These functions must be coordinated so they occur in the proper sequence, and they must be regulated so they occur slowly enough to allow complete digestion but quickly enough to supply the energy needs of the animal.

In the mouth cavity, food may be physically fragmented by teeth (in many vertebrates), by a radula (in snails), or by mandibles (in many arthropods). In most birds, food is ground by small stones in an early, muscular portion of the gut called the gizzard. Some animals, such as snakes, simply ingest whole prey with little or no fragmentation. Teeth in these species are angled backward to keep the prey moving in only one direction while being slowly swallowed. Stomachs and crops are storage chambers that enable animals to ingest relatively large amounts of food when it is available, and then digest it gradually. In these storage chambers, food may be further fragmented and mixed, and in most vertebrates it is an important site of digestion. Food delivered into the next section of the gut, the intestine, is in small particles, well mixed, and usually partially digested.

Most digestion occurs in the intestine, and nutrients, water, and ions are absorbed across its walls. Glands secrete digestive enzymes into the intestine, and other enzymes are produced and secreted by cells lining the intestine. The final segment of the intestine recovers water and ions and stores undigested wastes, or feces, so they can be released to the environment at an appropriate time or place. A muscular rectum near the anus assists in expelling feces.

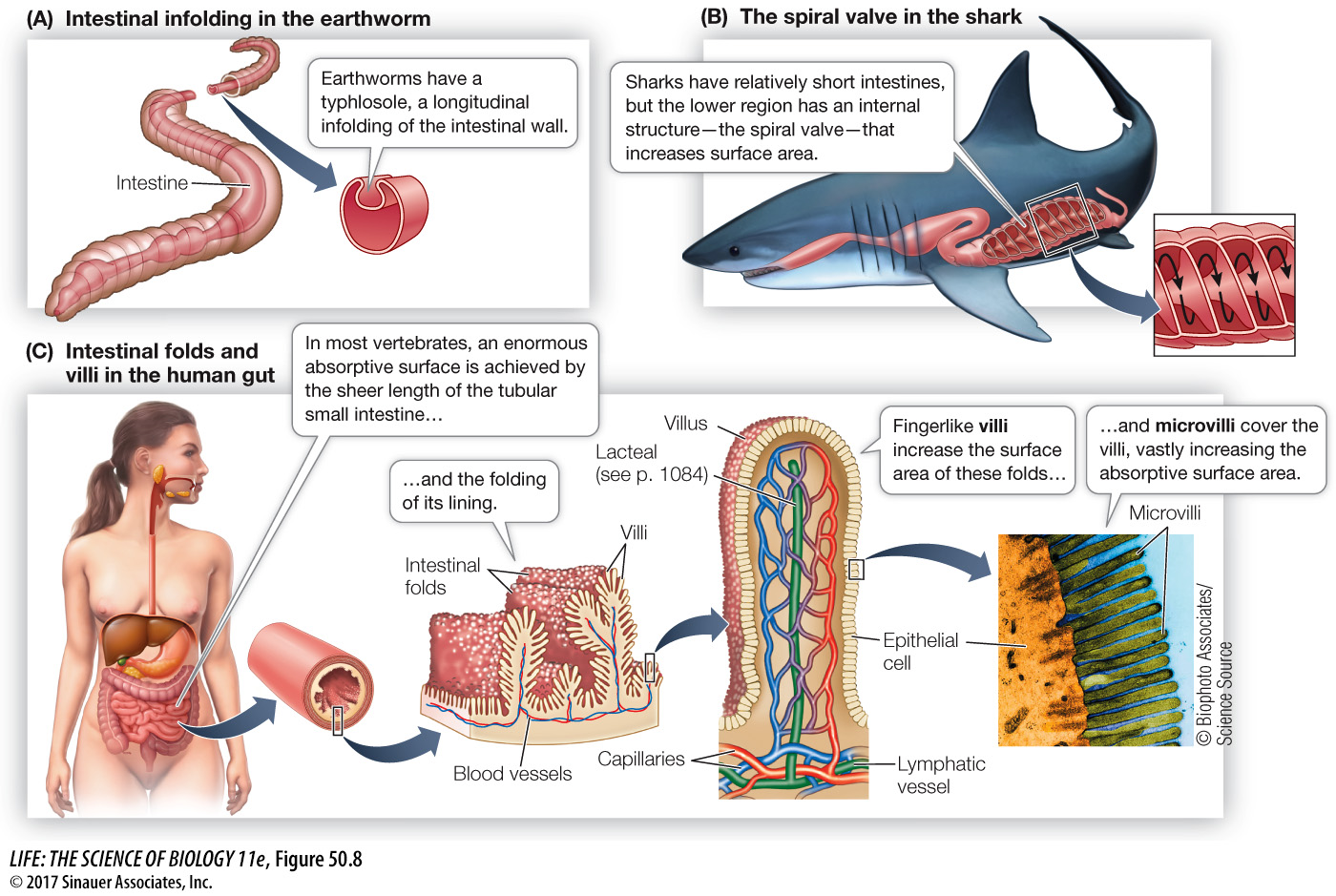

In many animals, the parts of the gut that absorb nutrients have greater surface areas than would be expected of a simple tube. The simplest way to increase the surface area of a tube without changing its diameter is to produce an infolding. Such an infolding of the gut, called a typhlosole, is seen in earthworms (Figure 50.8A). Sharks, which have large stomachs but short intestines, have a unique adaptation called a spiral valve (Figure 50.8B). The lower region of the intestine is enlarged and has an internal structure that forces the food to pass through it in a spiral fashion (like going down a spiral staircase). The walls of the spiral present a large surface area for absorption of nutrients. This spiral passage, however, will not accommodate large chunks of food or undigestible matter, so food remains in the stomach for a long time to be broken down, and some larger, undigestible items do not leave the stomach except by regurgitation.

1077

In humans, as in most other vertebrates, the wall of the intestine is highly folded, with the individual folds bearing legions of tiny fingerlike projections called villi (Figure 50.8C). The cells that line the surfaces of the villi, in turn, have microscopic projections called microvilli. The microvilli give the intestine an enormous internal surface area for absorbing nutrients.