Vertebrates are osmoregulators and ionic regulators

All aquatic vertebrates, with two exceptions, regulate the osmolarity of their extracellular fluids at around 300 mosm/L. In doing so, they are selective in which ions they conserve and which ions they excrete; thus they are ionic regulators and osmoregulators. One exception is the hagfish, a primitive jawless fish and a very ancient vertebrate group (see Figure 32.11). Hagfishes are osmoconformers as well as ionic conformers for most of the ions found in seawater. The other exception is members of the class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes, the sharks and rays). The cartilaginous fishes retain in their extracellular fluid two organic solutes, urea and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), that are products of protein metabolism. As a result, their extracellular fluid is slightly hypertonic to the seawater and they gain water by osmosis.

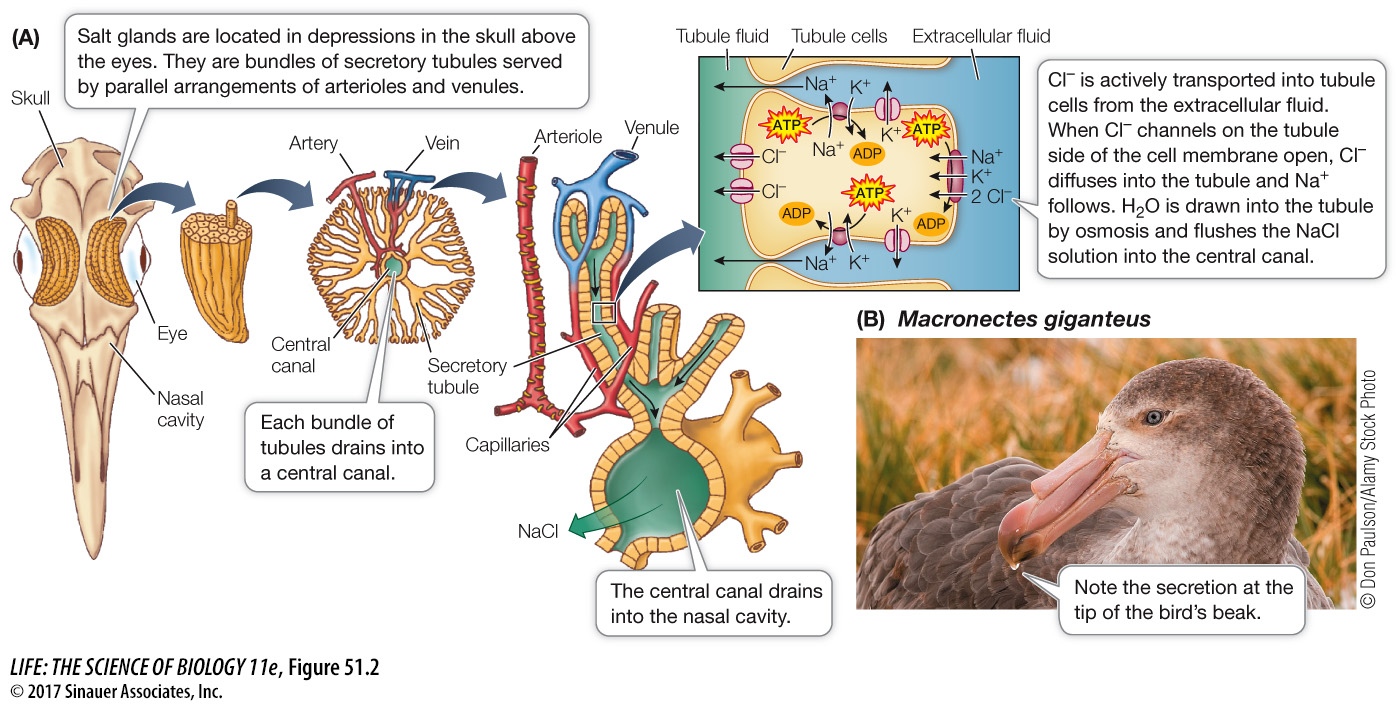

Terrestrial vertebrates obtain their salts mostly from food, and they regulate the ionic composition of their extracellular fluids by conserving some ions and excreting others. For example, herbivores have to conserve Na+ because most plants have low concentrations of Na+. In contrast, birds that feed on marine animals must excrete the excess sodium they ingest with their food. Such birds, which include penguins and gulls, excrete excess salt through nasal salt glands. These glands use secondary active transport of Cl– ions (with Na+ and some water following passively) into a series of canals and ducts to produce a concentrated solution of NaCl that empties into the nasal cavity (Figure 51.2). These birds can be seen frequently sneezing or shaking their heads to get rid of the salty droplets excreted from their nasal salt glands.