Some behaviors can be acquired only at certain times

Responsiveness to simple releasers is sufficient for certain behaviors such as begging behavior in gull chicks, but more complex information that cannot be genetically programmed is required for other behaviors. An example is parent–

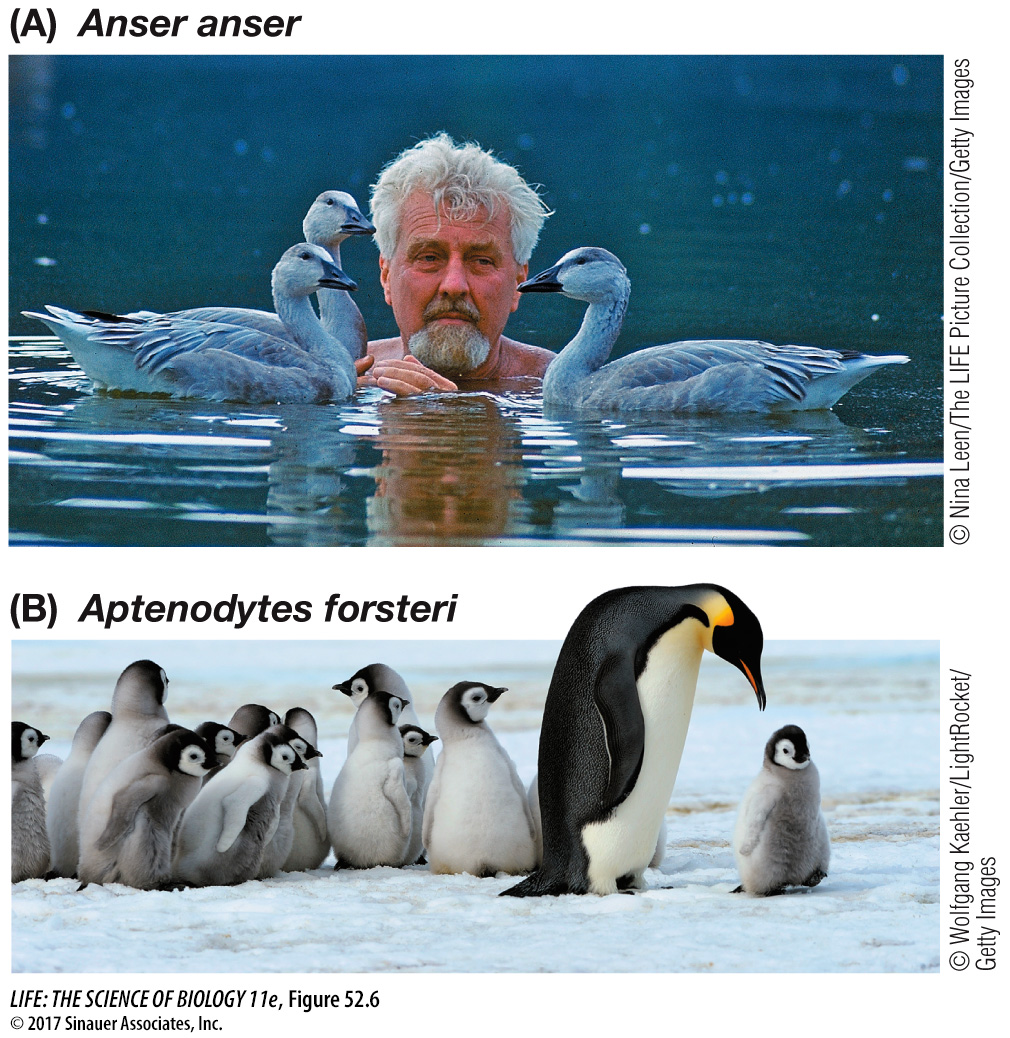

Konrad Lorenz demonstrated that young greylag geese (Anser anser) imprint on their parents between 12 and 16 hours after hatching. By positioning himself to be present during this critical period, Lorenz succeeded in imprinting goslings on himself. The imprinted goslings followed him around as if he were their parent (Figure 52.6A). In a subsequent experiment his assistants wore boots with different patterns on them. The goslings imprinted on the boots, and even in a situation that mixed different groups of goslings, they always sorted themselves out by following their “parental” boots.

Imprinting requires only a brief exposure, but its effects are strong and long-

The critical or sensitive period for imprinting may be determined by a brief hormonal state. For example, if a mother goat does not nuzzle and lick her newborn within 10 minutes after its birth, she will not recognize it as her own offspring later. For goats, the sensitive period is associated with peaking levels of the hormone oxytocin in the mother’s circulatory system at the time she gives birth and at the same time she is sensing the olfactory cues emanating from her newborn kid. A female goat rendered incapable of smelling before giving birth is unable to differentiate between her own kid and other kids after giving birth.