Territorial behavior carries significant costs

Territorial behavior is a good subject for cost–

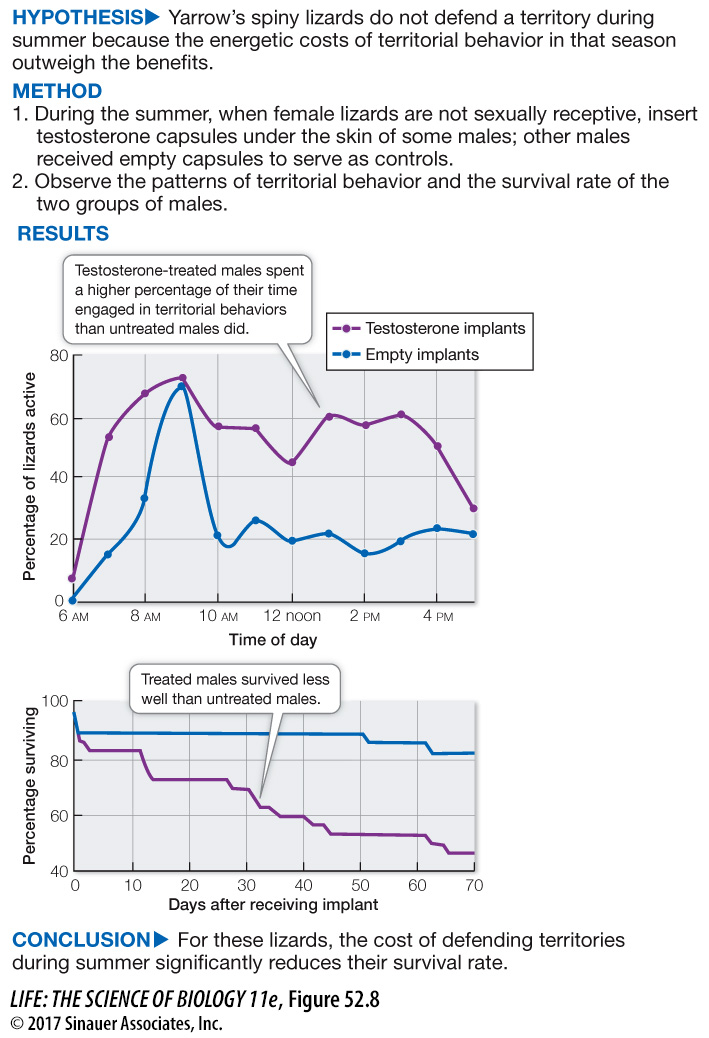

Territorial displays require considerable expenditure of energy, they make a male more vulnerable to predation, and they detract from the time he has for feeding or engaging in parental behavior. Michael Moore and Catherine Marler at Arizona State University performed an experiment to estimate the costs incurred by male Yarrow’s spiny lizards (Sceloporus jarrovii) when defending a territory. These lizards defend territories that include the home ranges of several females. Their territorial behavior is normally most intense during September and October when circulating testosterone levels of the males are high and the females are most receptive to mating. The researchers varied the intensity of the lizards’ territorial behavior by implanting testosterone capsules in some males in summer, when they are not normally highly territorial (Figure 52.8).

experiment

Figure 52.8 The Costs of Defending a Territory

Original Paper: Marler, C. A. and M. C. Moore. 1988. Evolutionary costs of aggression revealed by testosterone manipulations in free-

By using testosterone implants to increase territorial behavior, Michael Moore and Catherine Marler measured the costs to male Yarrow’s spiny lizards (Sceloporus jarrovii) of defending a territory during the summer, when they do not normally do so.

Testosterone-

Animation 52.1 The Costs of Defending a Territory

www.life11e.com/

The cost–

In some cases the resource that is defended is the female herself. Elephant seals spend most of their lives at sea, but females come to land at traditional beach sites to give birth to their pups. Male elephant seals arrive at these sites ahead of time and stake out territories through vigorous fighting (Figure 52.9B). When the females arrive on the beaches, they have to enter the territories of the males. As long as the male territory holder can fend off challengers, he will be able to mate with all the females using his piece of the beach.

One unusual form of male territorial behavior arises in situations in which neither food, nest sites, nor females are defended. A lek is an area where males gather for the purpose of engaging in intense displays of their territorial prowess aimed at impressing females and winning the opportunity to mate. Even though space is not limited, each male defends a small piece of real estate on which he performs a display (Figure 52.9C). Those territories closest to the center of the lek are the prime sites, and males compete intensely for those locations. The females visit the lek, observe the males, and generally mate with the males holding the prime sites. The benefit of this system to the female is that she is inseminated by a successful competitor, and therefore her offspring will carry the genes that contributed to his success. This is another example of sexual selection (see Key Concept 20.2). The costs of lekking to males are high, as they engage in continuous, intense territorial behavior that precludes eating, drinking, and sleeping until they are displaced. The benefit is the chance to maximize their fitness by mating with many females.