Fitness can include more than your own offspring

As humans, we readily understand the concept of extended family—

An individual’s fitness is increased by having offspring because those offspring carry the parent’s genes into the next generation. Fitness gained by producing offspring is referred to as direct fitness. However, an individual’s genes are carried into the next generation by more than his or her own offspring. In diploid organisms, two offspring of the same parents share, on average, 50 percent of the same alleles, and an individual is likely to share 25 percent of its alleles with its siblings’ offspring (nieces or nephews). Therefore, by helping parents and other relatives raise their offspring, an individual increases the transmission of those shared alleles to the next generation. Inclusive fitness is the individual’s direct fitness plus its indirect fitness: the reproductive success of the individual’s relatives, to the extent that those relatives share the individual’s alleles.

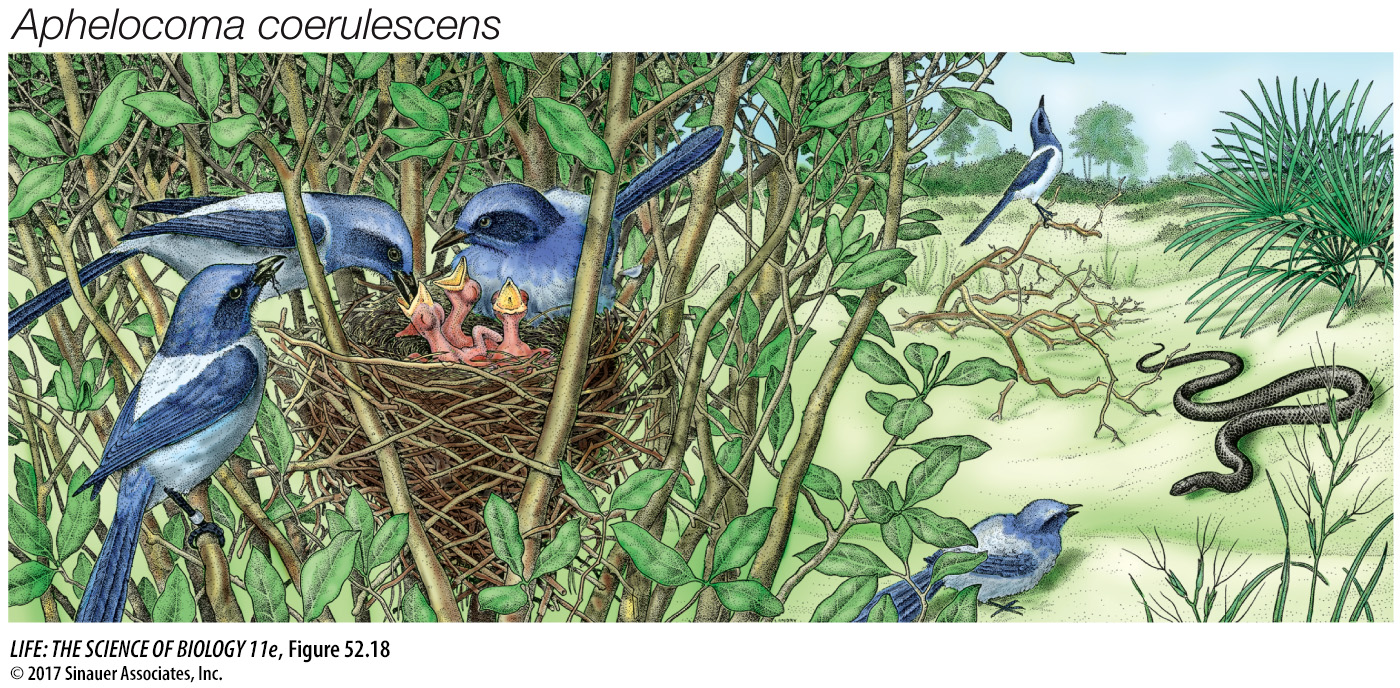

The maximization of inclusive fitness is the mechanism driving kin selection, selection for behaviors that increase the reproductive success of relatives even when they come at a cost to the performer. One example is “helping at the nest” behavior, which was studied extensively in Florida scrub-

The helpers are prior offspring of the mating pair and are usually 1–

3 years old. Young birds that attempt to breed have almost zero reproductive success.

Mating pairs with helpers have approximately three times the reproductive success of those without helpers.

These results support the conclusion that helper scrub-

1136

The concept of kin selection was formalized by W. D. Hamilton in what has become known as Hamilton’s rule. He argued that, for an apparent altruistic behavior to be adaptive, the fitness benefit of that act to the recipient times the degree of relatedness between the performer and the recipient has to be greater than the cost to the performer. This relationship was clearly stated years before by the eminent geneticist J. B. S. Haldane, who said during an argument about altruism that he would not be willing to risk his life to save his brother, but for two brothers or eight cousins, he would consider it.