Ethologists focused on the behavior of animals in their natural environment

An alternative approach to the study of animal behavior arose at the same time as behaviorism and focused on the various behaviors of animals in their natural environment. This field of study became known as ethology (Greek ethos, “character,” + logos, “study”). Ethologists were interested in a wide variety of species, their evolutionary relationships, and the ways in which their behaviors were adapted to their environments. The leaders of the ethology movement were Karl von Frisch, who discovered the dance language of honey bees; Konrad Lorenz, who discovered that the strong bond between parent and offspring develops during a “critical period” following birth; and Niko Tinbergen, who studied inborn patterns of behavior commonly known as instincts. These three scientists shared the Nobel Prize in 1973 for “their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behavior patterns.” Their work laid the foundation for modern research on animal behavior.

1117

Ethologists were mainly interested in species-

are performed without learning.

are stereotypic (that is, they are performed the same way each time).

cannot be modified by learning.

The ethologists called such behaviors fixed action patterns.

Ethologists performed deprivation experiments to demonstrate the genetic determination of a behavior. They raised animals in an environment devoid of opportunities to learn their species-

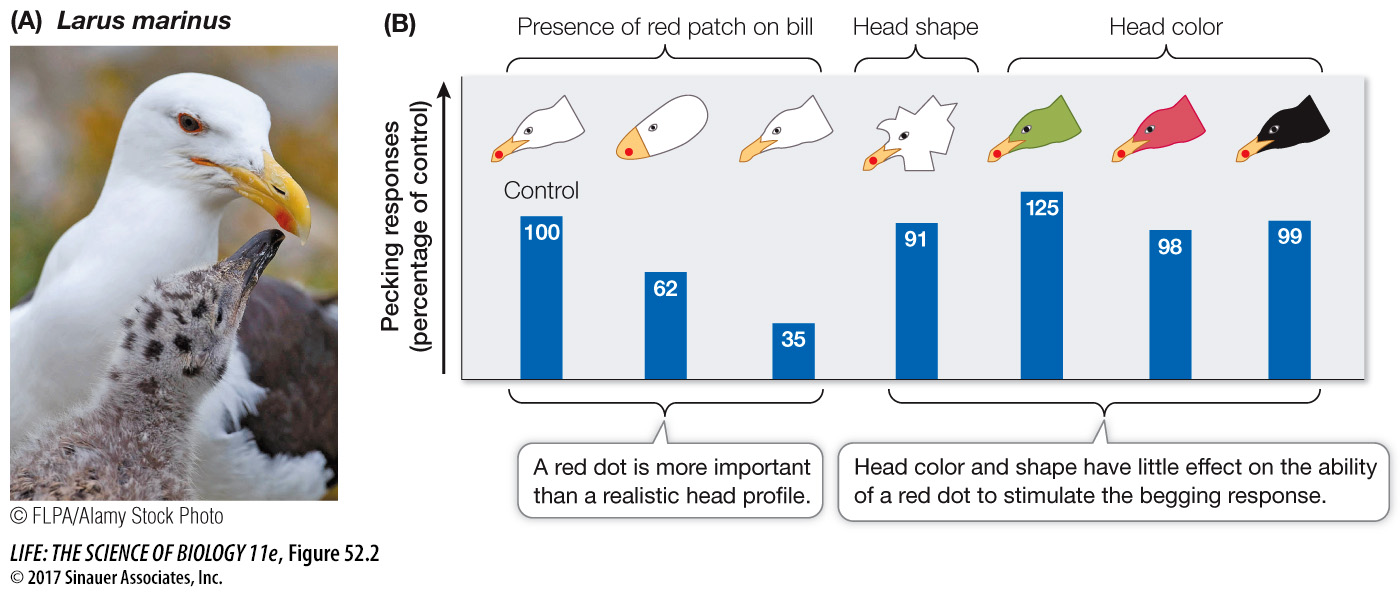

Fixed action patterns are usually responses to specific stimuli. The ethologists carefully characterized such stimuli, which they called releasers. In general, releasers are simple subsets of the information available in the environment. For example, Tinbergen studied the begging behavior of gull chicks. Adult gulls have a red dot on their lower bill. When a parent returns to the nest to feed its chicks, the chicks peck on the red dot, which stimulates the parent to regurgitate food (Figure 52.2A). Experimenters investigated what stimulated the chicks to peck their parents’ bills. Models of gull heads of different shapes and colors were tested (Figure 52.2B), as were models of a beak without a head. The results showed that the red dot was necessary for the release of chick pecking behavior. In fact, a pencil with a red eraser elicited a more robust pecking response than an accurate model of a gull head without a red dot.

Question

Q: Why do you think sign stimuli are rather simple components of all of the sensory information available?

It is unlikely that specific recognition of a complex stimulus could be genetically programmed.