Single gene mutations can alter behavioral phenotypes

Are you a morning person or a night person? Some people are early risers and function best in the morning, and others have their best work hours late at night. It is possible that this big difference in the behavior of individuals could be due to differences in a single gene. This story begins with fruit flies, Drosophila. Fruit flies, like virtually all organisms, have daily rhythms that continue even if all external time cues are taken away. But without external time cues, these rhythms do not span exactly 24 hours, which is why they are called circadian (circa, “about,” + dies, “ a day”). Investigators using chemicals to randomly mutate genes in Drosophila found one gene that controlled the duration, or period, of the circadian rhythms of the flies. This gene was named per for period, and variants of this gene caused short or long circadian periods. We now know that there are many more genes involved in circadian rhythms, and that these genes are highly conserved in organisms ranging from Drosophila to humans. One variant of the per gene in humans results in familial advanced phase sleep syndrome. The affected individuals have short circadian rhythms and tend to go to sleep and wake up earlier than others.

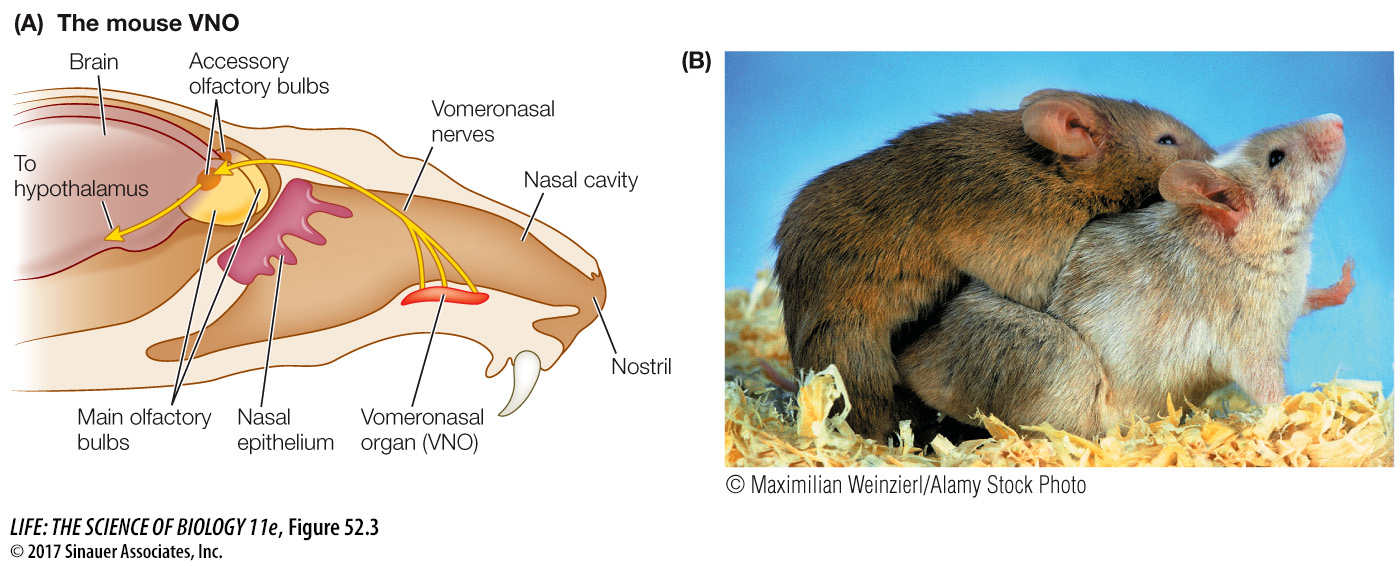

That single genes can influence even complex behaviors should not be surprising. Many behaviors depend on a particular signaling molecule or a particular receptor molecule, and a change in the gene for that signal or receptor could therefore dramatically change the behavior. For example, mutation in a gene for an olfactory receptor could result in the ability to sense a different odorant. Even changes in the expression pattern of a gene can alter a complex behavior. As we discussed at the beginning of Chapter 7, prairie voles are highly monogamous, and both sexes give much parental care to their young. Montane voles do not form pair bonds, are promiscuous, and provide a shorter period of maternal care than prairie voles. The difference between these two species lies in the expression of the receptors for the neuropeptides vasopressin (males) and oxytocin (females): there are far fewer receptors for these neuropeptides in the brains of montane voles. We’ll return to the social systems of voles in Key Concept 52.6.

1119