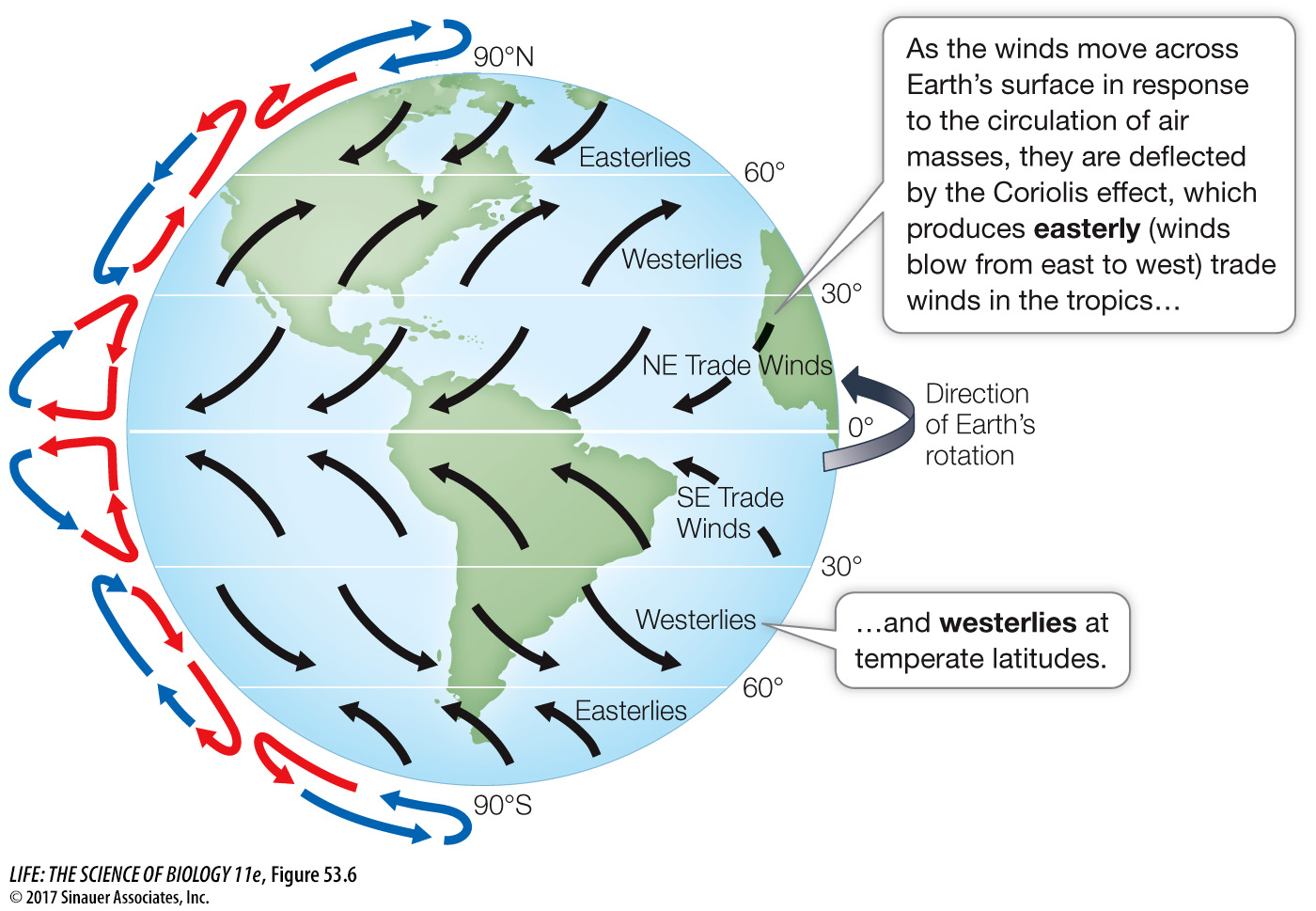

Earth spins on an axis, producing prevailing winds and ocean currents

You have seen that Earth’s spherical shape creates predictable patterns of temperature and precipitation, but Earth’s rotation, which moves east to west, is responsible for generating global wind and ocean currents. Because Earth is a sphere, the velocity of its rotation around its axis is fastest at the equator, where its diameter is greatest, and is slowest close to the poles. This difference creates the Coriolis effect, which is the deflection of air or water as a result of differences in Earth’s rotational speed at different latitudes. For example, air traveling toward the equator (driven by the circulation patterns described above and in Figure 53.5) moves at a slower speed than that of the planet beneath it and is thus deflected to the west. Conversely, air traveling toward either pole is moving faster than that of the surface beneath it and is deflected to the east. This interaction of Earth’s rotation and north–

1147

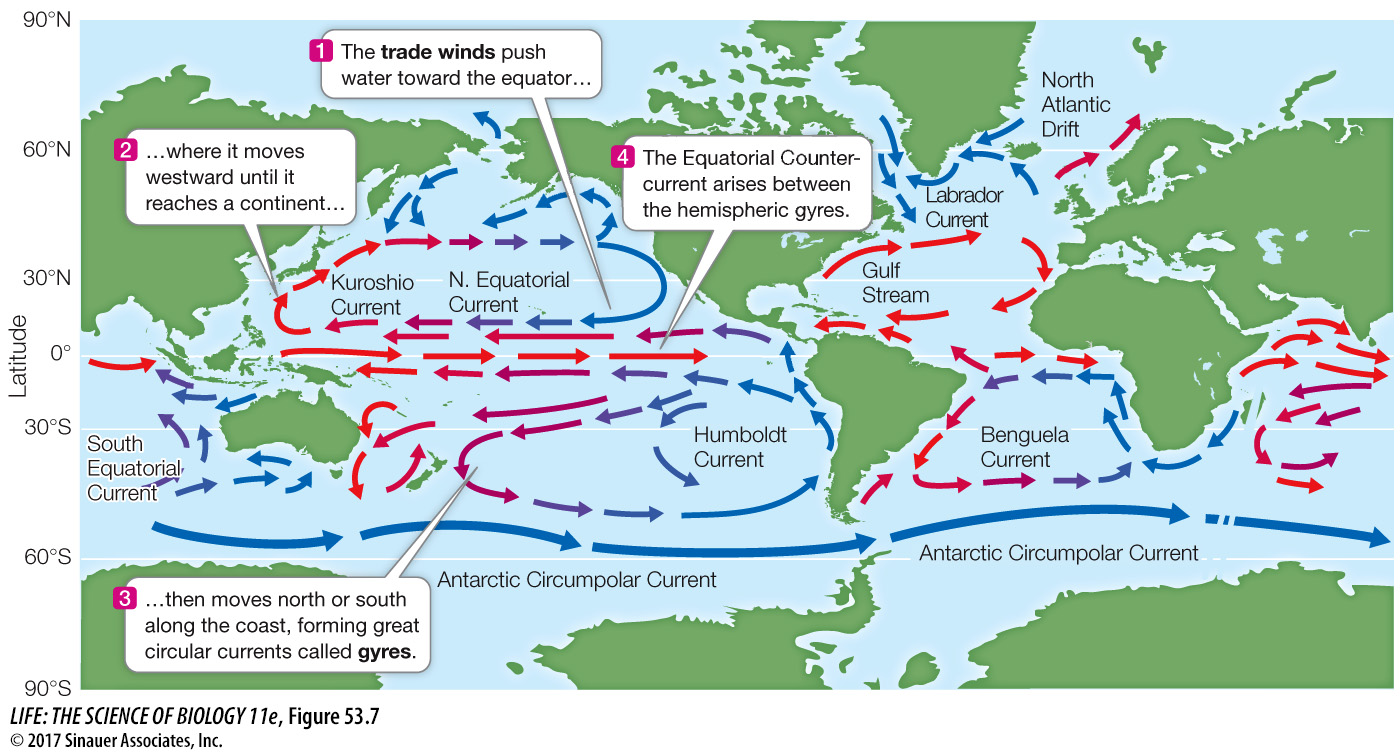

How, then, are the circulation patterns of ocean currents generated? Ocean currents are driven by prevailing winds, which move water by means of frictional drag. The trade winds, for example, cause currents to converge at the equator and move westward until they encounter a continent (Figure 53.7). At that point, the strong Equatorial Countercurrent brings some of the water back eastward. The remaining water divides, some moving northward and some southward along continental shores. These patterns of water movement set up rotating circulation patterns called gyres (Greek gyros, “spiral”), which rotate clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

Because ocean currents transport heat, they have a tremendous effect on Earth’s climates. The poleward movement of warm water from the tropics transfers large amounts of heat to high latitudes. The Gulf Stream, for example, carries warm water from the tropical Atlantic Ocean (including the Gulf of Mexico) north across the Atlantic to northern Europe, making Europe’s climate considerably milder than that of corresponding latitudes in North America. Similarly, currents flowing toward the equator from high latitudes bring cool, wet winters to some western coastal regions that are otherwise warm and dry.