Terrestrial biomes reflect global patterns of temperature and precipitation

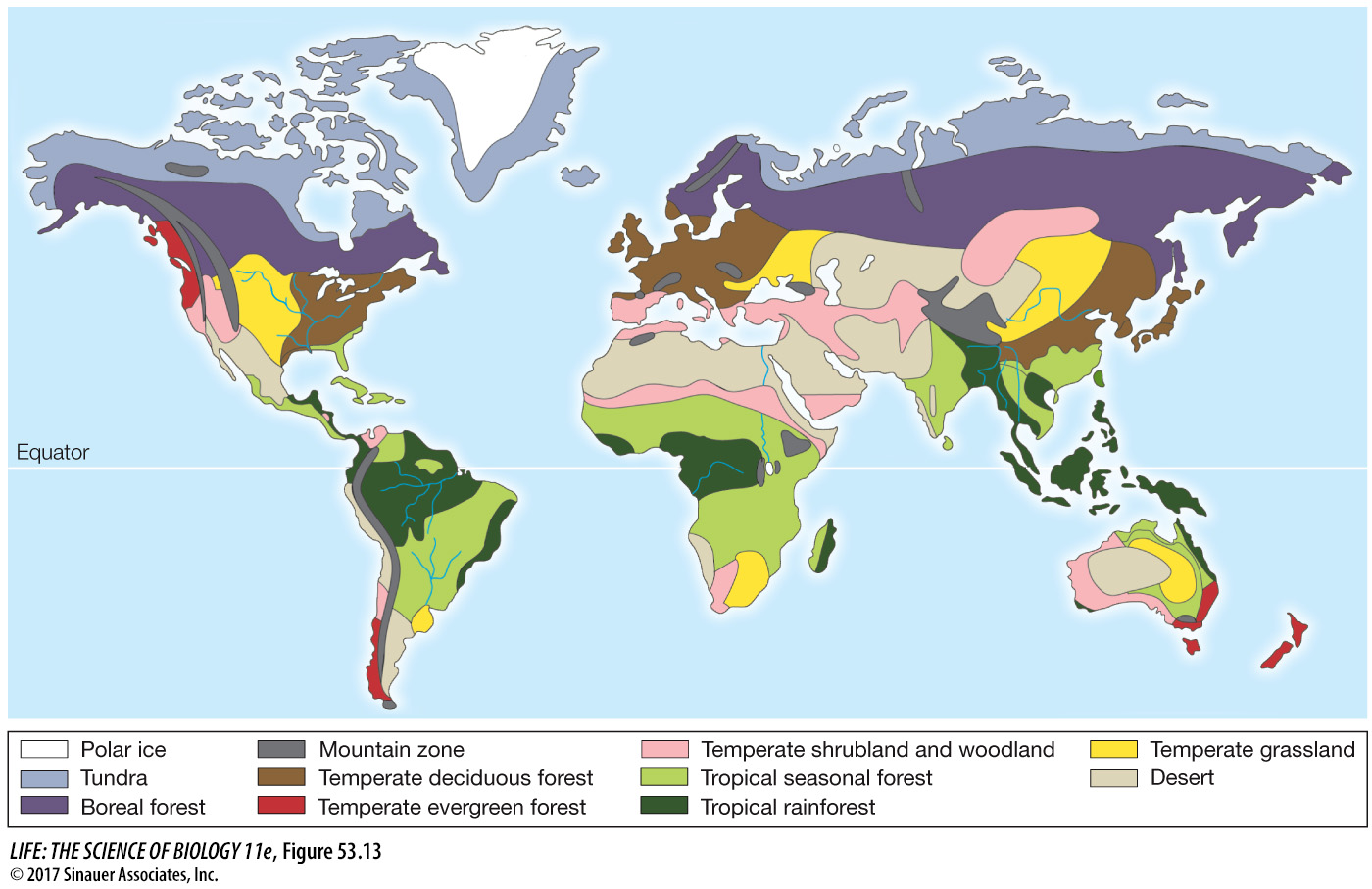

Biomes are groupings of ecologically similar organisms shaped by the environment in which they are found. The classification of biomes is most often and easily applied to terrestrial systems. Ecologists classify terrestrial biomes principally by the growth forms of their dominant plants, which reflect the evolution of those plants under annual patterns of temperature and precipitation.

The same classic types of biomes may be widely separated, occurring on different continents, depending in large part on the presence of suitable climatic conditions (Figure 53.13). For example, the desert biome occurs in such distant locations as Arizona in the North American Southwest and the Namib Desert in Africa; both locations are extremely dry and dominated by succulent plants such as cacti and by drought-

*connect the concepts Plants growing in a particular type of environment (e.g., the desert) may display similar growth forms (e.g., succulence). See Key Concept 38.3.

1153

Question

Q: Does the Northern or Southern Hemisphere have a greater number of biomes? What do you think might determine this difference?

The northern hemisphere has more biome types. This is likely a consequence of the northern hemisphere having much more land area than the southern hemisphere, creating the opportunity for a diversity of temperature and rainfall regimes.

Activity 53.1 Biomes

www.Life11e.com/

Activity 53.2 Aquatic Biomes

www.Life11e.com/

In the following pages we briefly describe seven terrestrial biomes (a subset of those shown in Figure 53.13). For each, a plot of the seasonal patterns of temperature and precipitation—

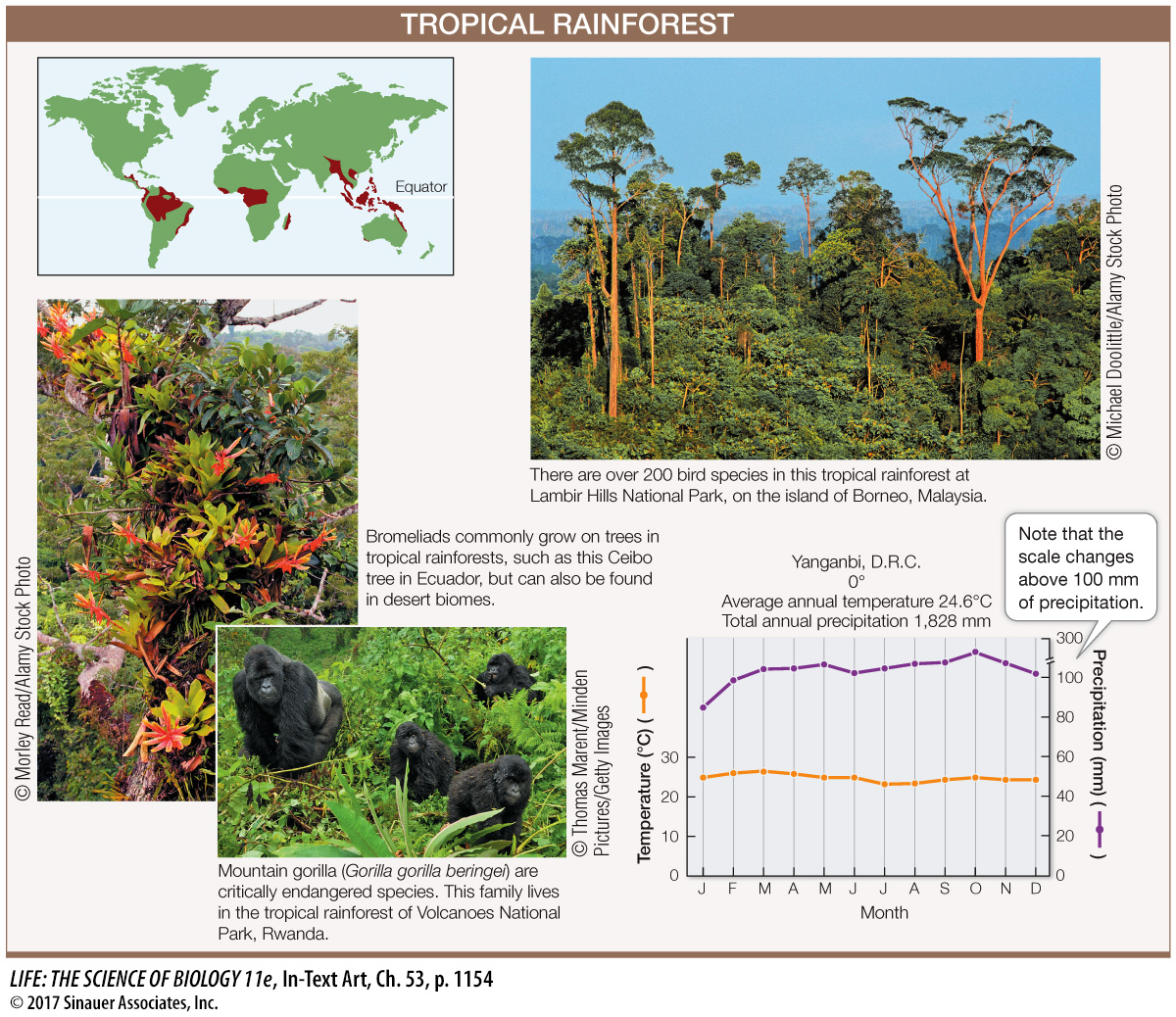

TROPICAL RAINFOREST The tropical rainforest biome is found in equatorial regions where rainfall and temperatures are high year round. With no season unsuitable for growth, it is the most productive and species-

Tropical rainforests provide humans with a range of products, including fruits, nuts, medicines, fuel, pulp, and furniture wood. Rainforests, however, are currently being cut down or converted to agriculture at a rate of almost 1 percent per year. In some cases, rainforests are recovering but the soils are often nutrient-

1154

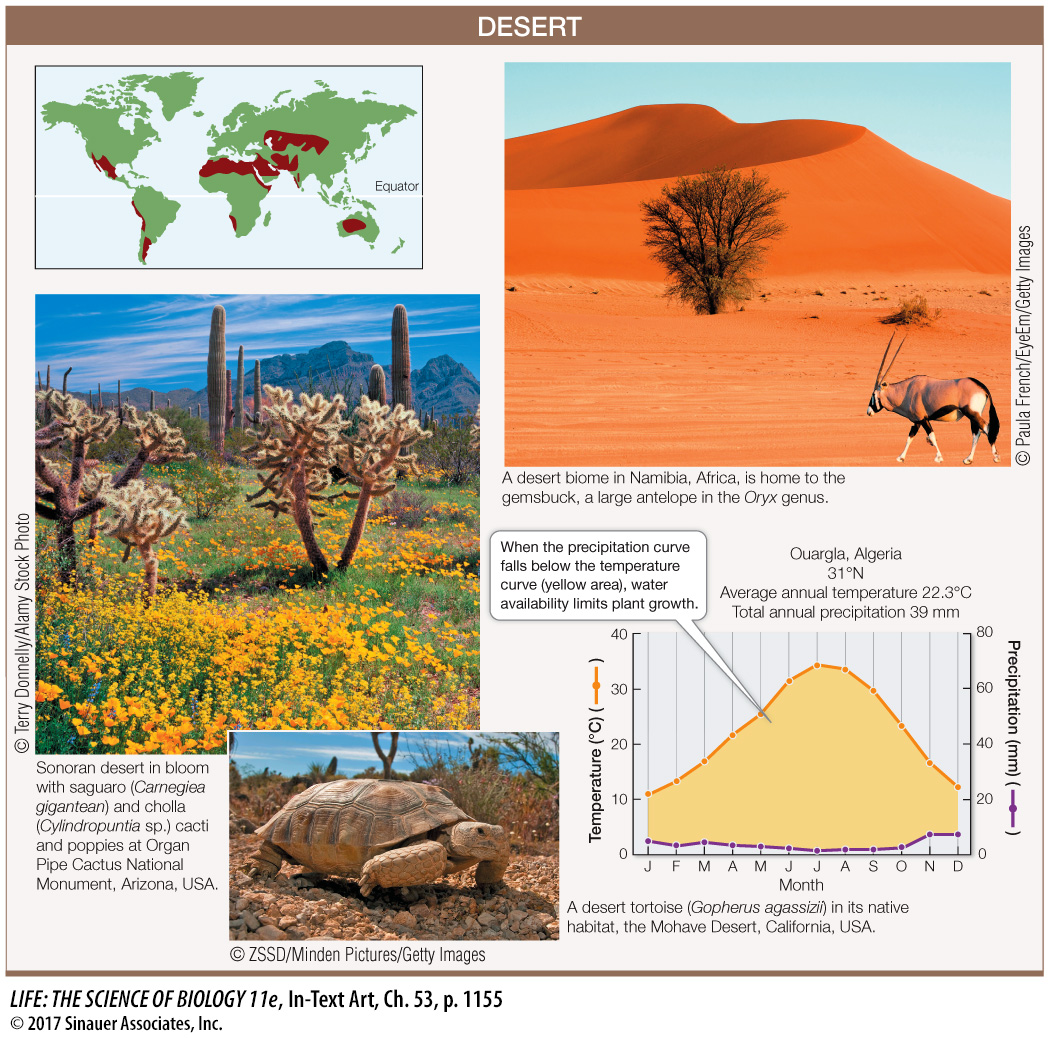

DESERT The desert biome is concentrated in two belts, centered around 30°N and 30°S latitude (where warm, dry air sinks under high atmospheric pressure; see Figures 53.4 and 53.5). The driest of these regions, where rains rarely fall, are far from the oceans, as in the center of Australia and the middle of the Sahara in Africa.

Desert plants have several structural and physiological adaptations that help them conserve water, as described in Key Concept 38.3. Small desert animals are inactive during the hottest part of the day, remaining in underground burrows. Desert mammals have physiological adaptations for conserving water, including a reduced number of sweat glands and kidneys that produce highly concentrated urine. Many desert animals require no water beyond what they can extract from the carbohydrates in their food.

Humans have used deserts for livestock grazing and agriculture for centuries. Deserts can be irrigated from deep wells or distant mountains, but such efforts typically fail as a result of salinization, the buildup of salts from the evaporation of irrigation water.

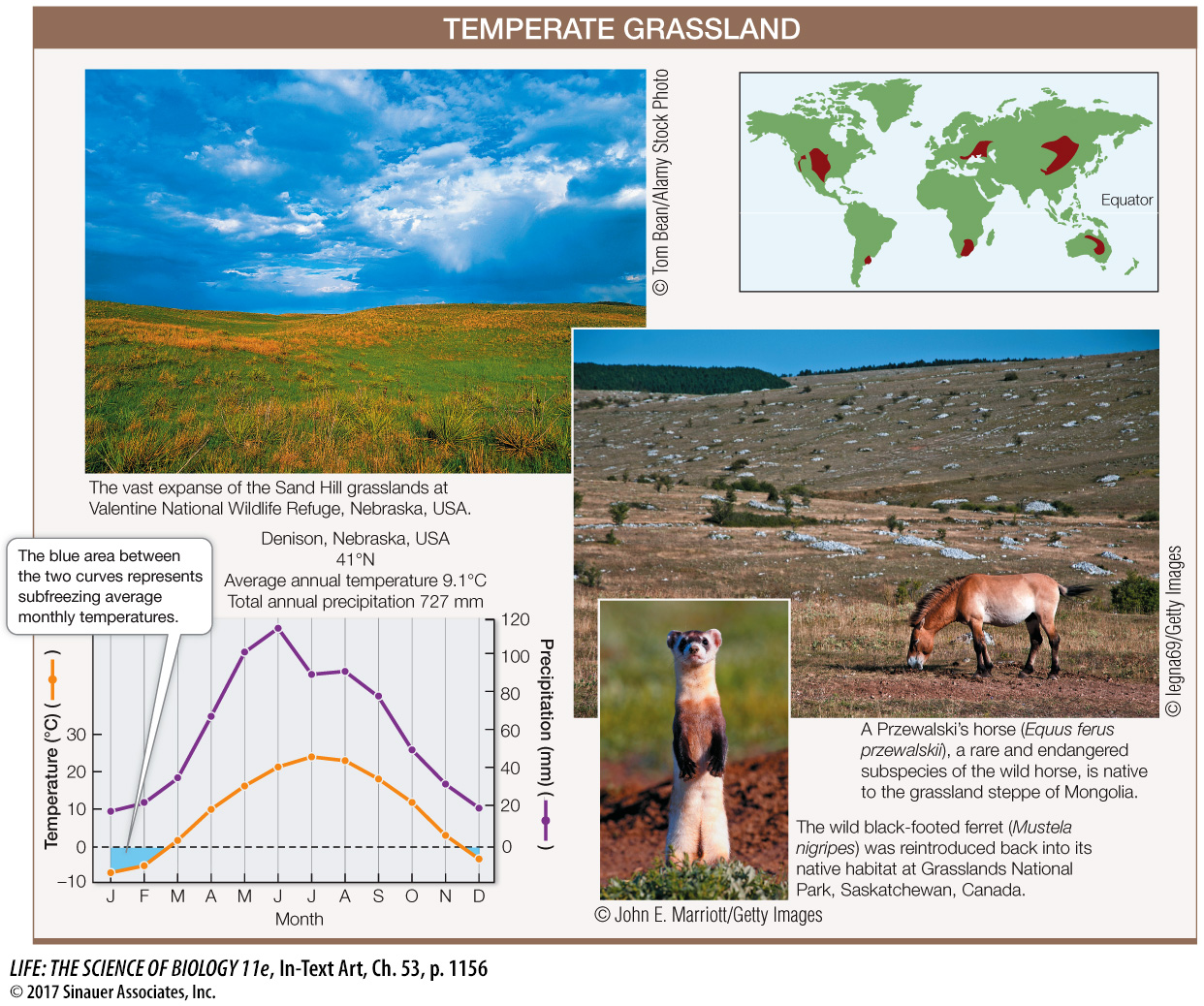

TEMPERATE GRASSLAND Temperate grasslands are found in many parts of the world, all of which are relatively dry for much of the year. Most grasslands, such as the pampas of Argentina, the veldt of South Africa, and the Great Plains of North America, have hot summers and relatively cold winters. In some grasslands, most of the precipitation falls in winter (as in California grasslands); in others, the majority falls in summer (as in the Great Plains and the Russian steppe).

Grassland vegetation is structurally simple but rich in species of perennial grasses and forbs (herbaceous plants). Grassland plants support herds of large grazing mammals and are adapted to grazing and to fire. They store much of their energy underground and resprout quickly after being burned or grazed. There are comparatively few trees in temperate grasslands because trees cannot survive the periodic fires or the dry conditions.

1155

The topsoil of grasslands is usually rich and deep, and thus exceptionally well suited to growing crops such as corn and wheat. As a consequence, most of the world’s temperate grasslands have been turned over to agriculture and no longer exist in their natural state.

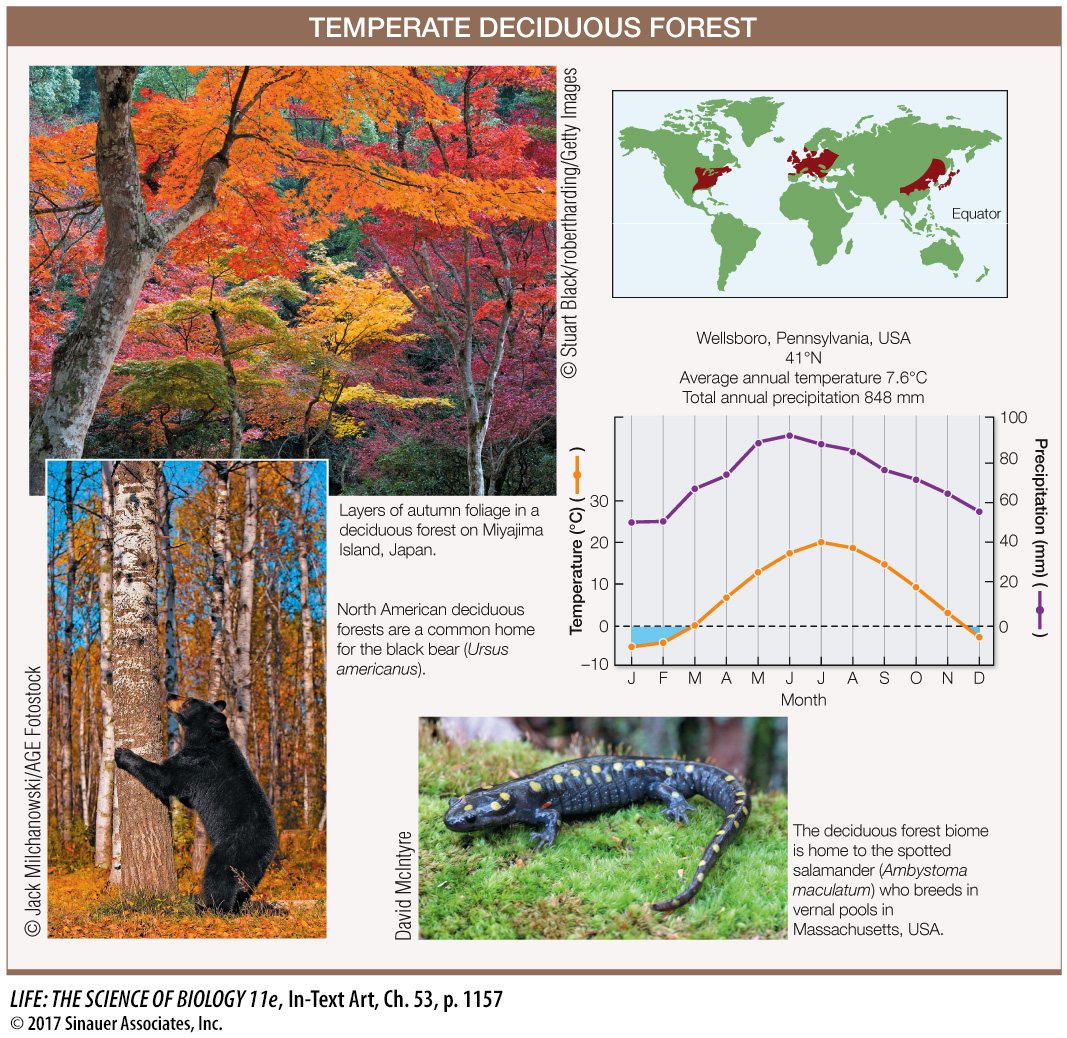

TEMPERATE DECIDUOUS FOREST The temperate deciduous forest biome is found in eastern North America, eastern Asia, and Europe. Temperatures in these regions fluctuate dramatically between summer and winter, although precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. The deciduous trees that dominate these forests lose their leaves during the cold winters and produce new leaves during the warm, moist summers.

The temperate deciduous forests have many more species than boreal forest ecosystems. Those with the highest species richness occur in the southern Appalachian Mountains of the United States and eastern China and Japan—

Although many animals are permanent residents of deciduous forests, some (including many birds) migrate to find food resources and escape the winter cold. Others that remain through the winter hibernate (see Key Concept 39.5), often in underground burrows. Many insects pass the winter in a state of diapause (suspended development), the onset of which is triggered by the decreasing hours of daylight—

1156

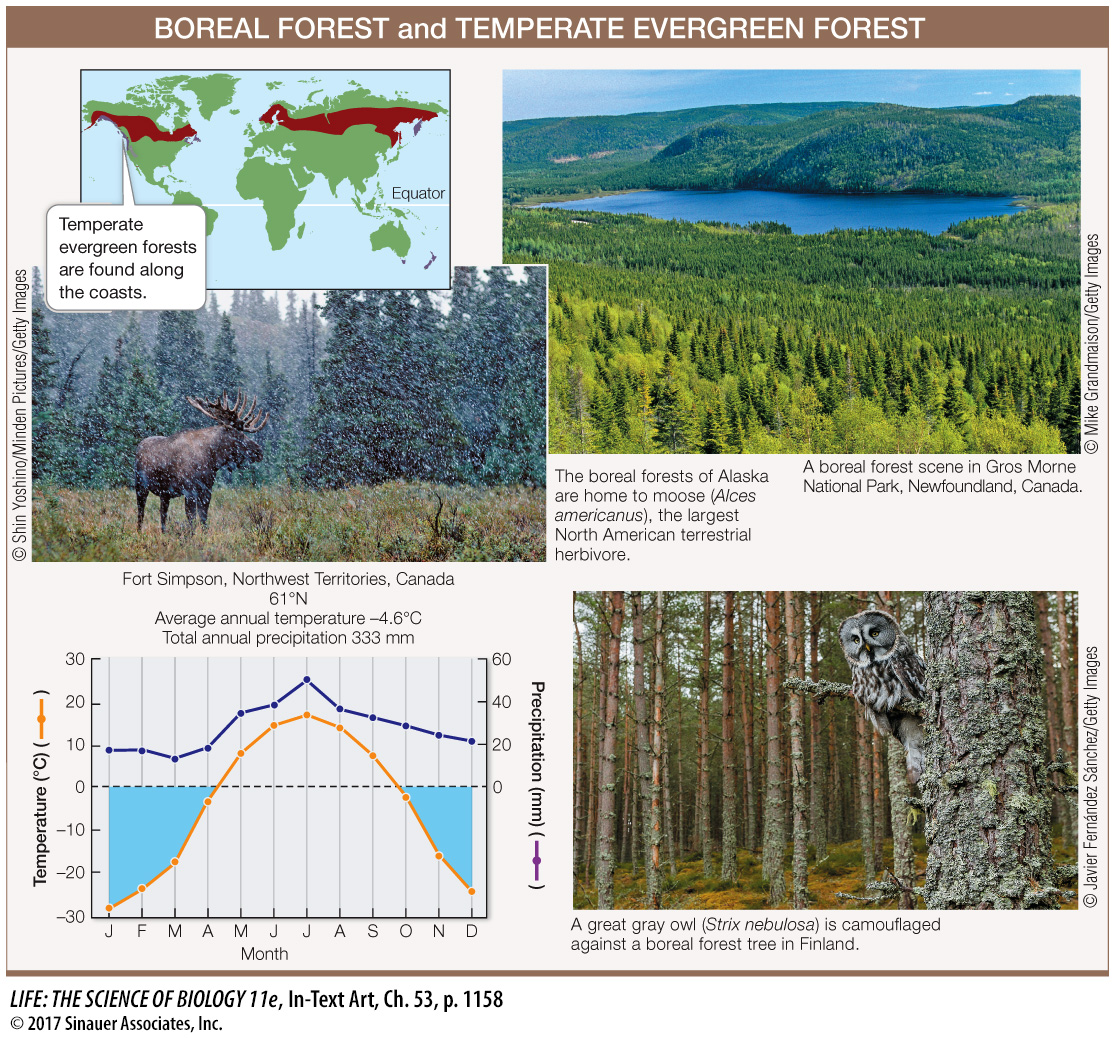

BOREAL FOREST AND TEMPERATE EVERGREEN FOREST The boreal forest biome (also known as taiga) occurs just above 50°N but below Arctic tundra, and at elevations below alpine tundra on temperate-

The dominant mammals of the boreal forest, such as moose and hares, eat leaves, but the seeds in conifer cones support a variety of rodents, birds, and insects. Many small mammals hibernate in winter, but voles, lemmings, and mice remain active under the snowpack, serving as food for predators such as foxes and owls.

The temperate evergreen forest biome occurs along the coasts of continents in both hemispheres at middle to high latitudes, where winters are mild and wet and summers are cool and dry. In the Northern Hemisphere, the dominant trees in temperate evergreen forests are conifers, some of which are the world’s most massive tree species (including the giant sequoia and coast redwood). In the Southern Hemisphere, the dominant trees are southern beeches (Nothofagus), some of which are evergreen.

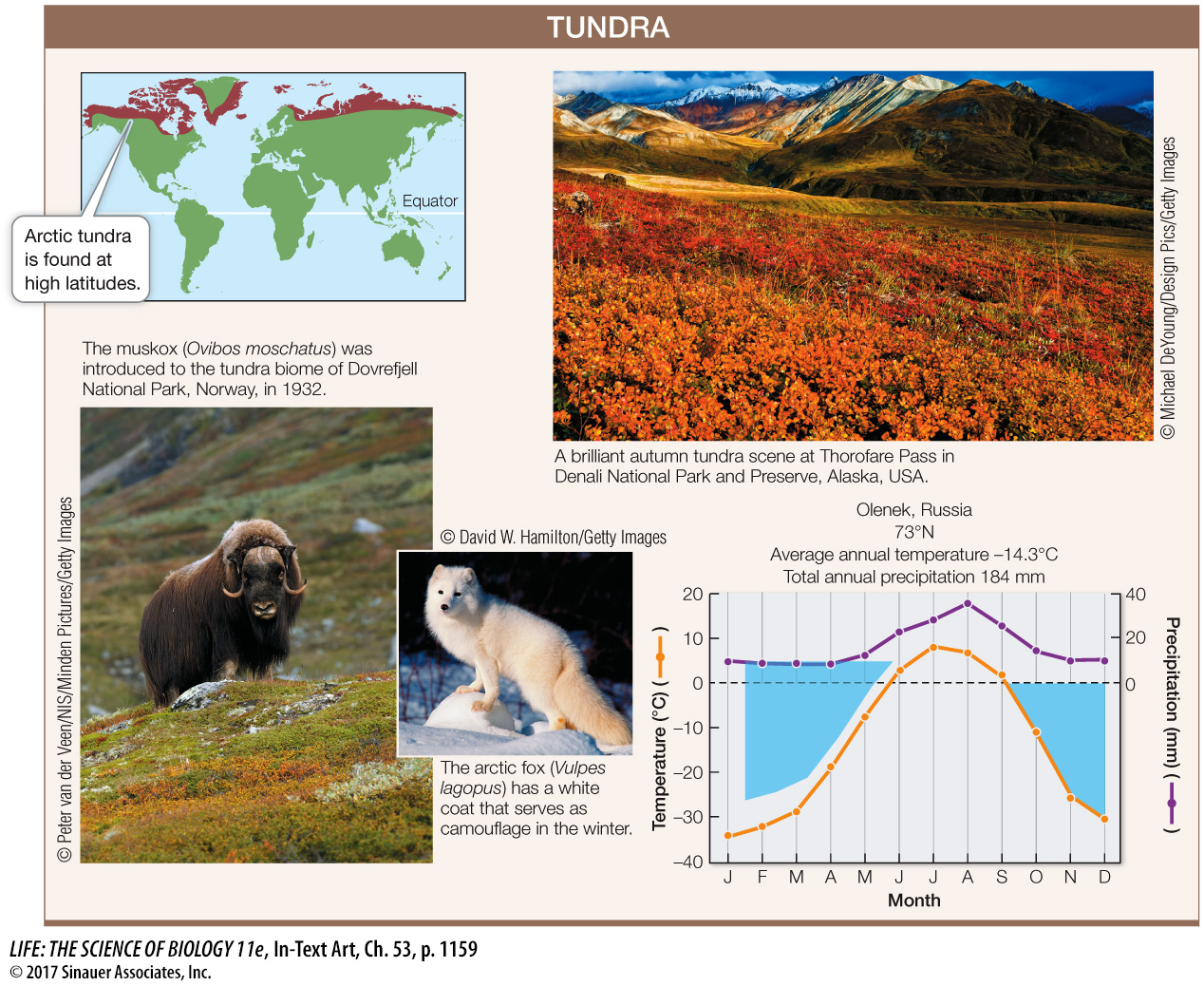

TUNDRA The tundra biome is found at high latitudes (above 65°) characterized by low temperatures and a short growing season. This biome is underlain by permafrost—

Tundra plants have several structural and physiological adaptations that help them conserve heat, as described in Key Concept 38.3. Most animals are either summer migrants or are dormant for much of the year. Resident birds and mammals, such as the willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) and Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), have thick fur or feathers that may change color with the seasons, from brown in summer to white in winter.

1157