Humans exert a powerful influence on biogeographic patterns

1163

The theory of island biogeography has provided surprising insight into the role human’s play in regional biogeographic patterns. As you saw in Key Concepts 53.3 and 53.4, Earth’s biomes are becoming smaller and more fragmented by local-

The fragmentation of the Amazon rainforest led Thomas Lovejoy and his colleagues to initiate, in 1979, one of the largest and longest-

investigating life

The Largest Experiment on Earth

experiment

Original Paper: Ferraz, G. et al. 2003. Rates of species loss from Amazonian forest fragments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 100: 14069–

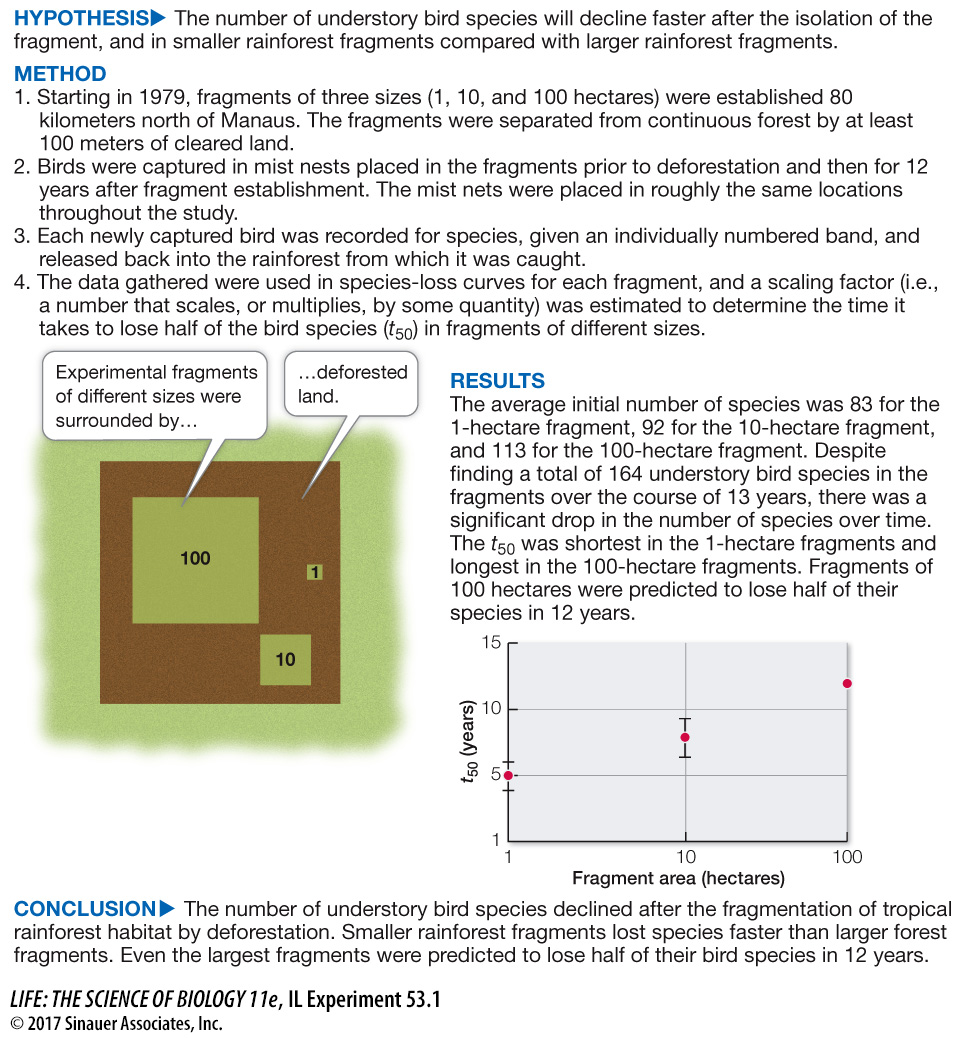

Thomas Lovejoy and his colleagues asked what was the minimum area needed to maintain species diversity in the rainforest fragments created by logging near Manaus, Brazil. They conducted an experiment, starting in 1979, that took advantage of an existing Brazilian law that required landowners who cut rainforest to leave half of it untouched. In 2003, Ferraz and colleagues reported on one particular aspect of the experiment: the number of forest understory birds living in different-

Animation 53.4 Edge Effects

www.Life11e.com/

work with the data

The data in the graph shown in the experiment can be used to calculate a scaling factor for the time it takes to lose half of the bird species within a fragment. The scaling factor shows that to increase the t50 (i.e., the time it takes fragments to lose half their species) by 10-

QUESTIONS

Question 1

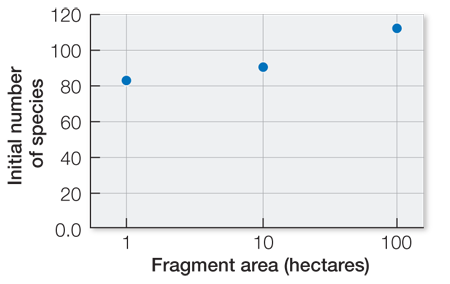

Graph the initial numbers of bird species by the size of the fragment area. Do these fragments follow the species–

Yes, there is a positive relationship between number of bird species and size of the fragment area.

Question 2

Suppose you are consulting for the Brazilian government on the conservation of rainforests near Manaus. Assuming that the t50 for 1 hectare is 5 years, what is the minimum size that a rainforest fragment in the Manaus area needs to be to ensure that half of the bird species remain 50 years after the deforestation event that isolated them? How about a century after deforestation?

The scaling factor shows that to increase the t50 (i.e., the time it takes fragments to lose half their species) by 10-

Question 3

Suppose it takes 100 years for rainforests to fully recover after a deforestation event in the Manaus region. Given that the average size of a rainforest fragment in this area is no bigger than 1,000 hectares, will the number of species decline by half before the recovery of rainforest occurs around the largest fragments?

Yes, because the average area would need to be 10,000 hectares to ensure that half the species would remain after 100 years.

A similar work with the data exercise may be assigned in LaunchPad.