Population dynamics are controlled by the physical environment, biological interactions, and dispersal

Even though we know that populations fluctuate in space and time, determining the factors responsible for this variation can be challenging. Ecologists recognize three main factors that affect population dynamics and that act simultaneously to set limits for populations and species: the physical environment, biological interactions, and dispersal.

As you saw in Chapter 53, the distribution and abundance of species are highly dependent on the physical environment; factors such as climate, topography, and even human infrastructure set physiological limits for species. Thus it makes sense that the physical features of the environment strongly limit a population’s geographic extent and size through time. You saw this for Clematis, whose populations are restricted to dry, rocky limestone soils, resulting in a patchy distribution pattern.

Likewise, many types of biological interactions affect population dynamics. Interbreeding among individuals within populations affects their size and extent—in fact, many populations can be defined by the genetic similarity of the individuals within a given area (see Key Concept 20.4). For example, populations of wild endangered salmon, which look nearly identical to hatchery-raised salmon, can be assessed for population size using genetic techniques that allow differentiation among populations. In addition, because individuals within populations share similar resources, intraspecific competition (competition for shared resources by individuals of the same species) can be critical in controlling population size, as you will see in Key Concept 54.2. *Interspecific interactions (interactions among individuals of different species) are another important factor in controlling population dynamics.

*connect the concepts Interspecific interactions such as competition, predation, and positive interactions (i.e., mutualisms and commensalisms) often set the upper limits on the number of individuals within populations. See Chapter 55.

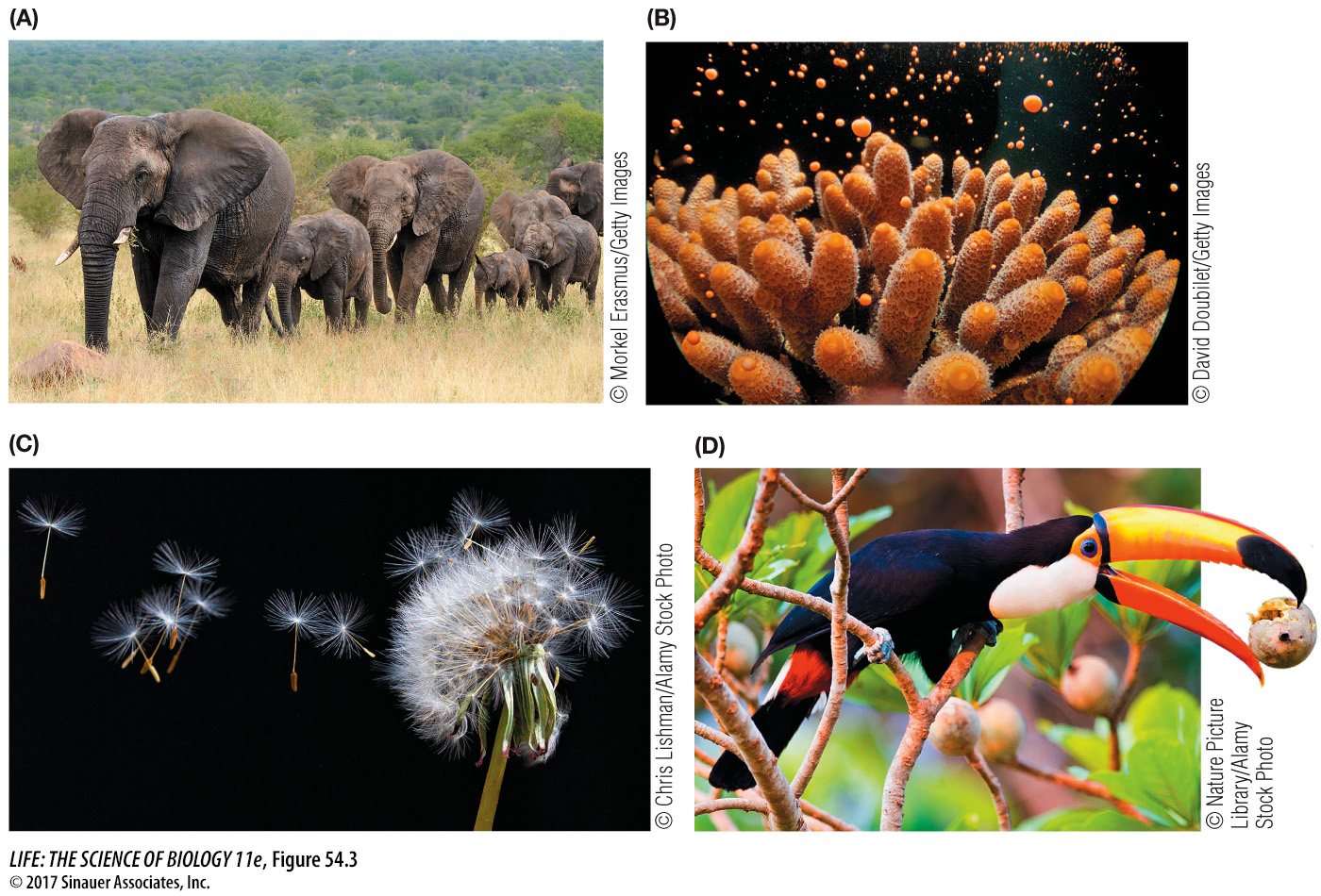

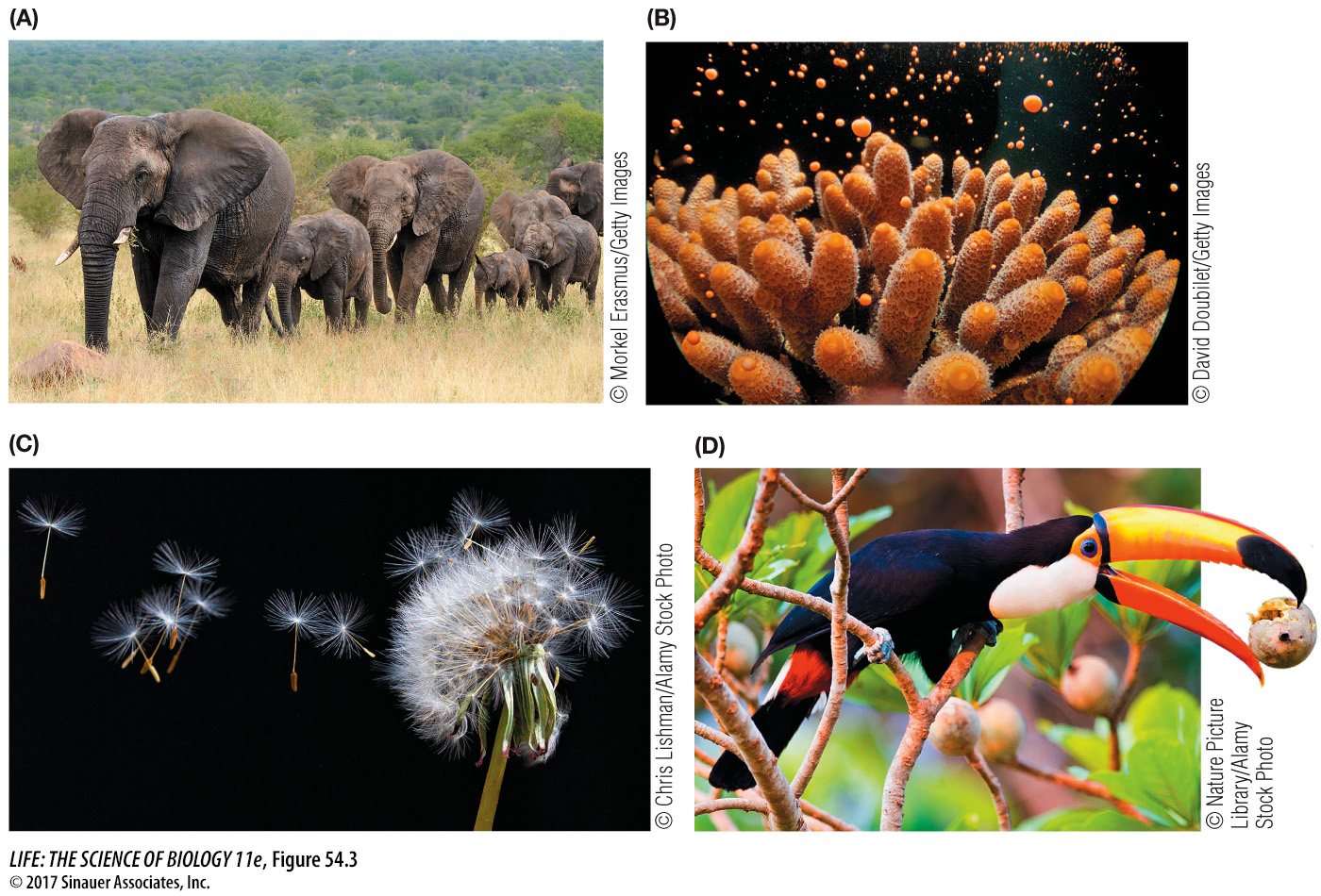

Finally, dispersal can be a critical factor controlling population dynamics. Dispersal comes in many forms. It can be active when movement is controlled by the individual, such as you might see with elephants; passive when movement is controlled by the physical environment, as in corals and dandelions; or facilitated by active agents, such as birds or bats dispersing seed-laden fruits (Figure 54.3). Dispersal is a mechanism that can reduce competition for resources, either with a parent or another individual within the population. In addition, dispersal allows individuals to escape a harsh physical environment. Thus dispersal serves as a mechanism to reduce the probability of local extinctions of populations by spreading the risk among multiple populations that are geographically separated (see Key Concept 54.4).

Figure 54.3 Different Dispersal Mechanisms of Organisms (A) Elephants actively disperse, (B, C) corals and dandelions disperse passively, and (D) seeds within fruits are typically dispersed by an active agent, in this case, a toco toucan.

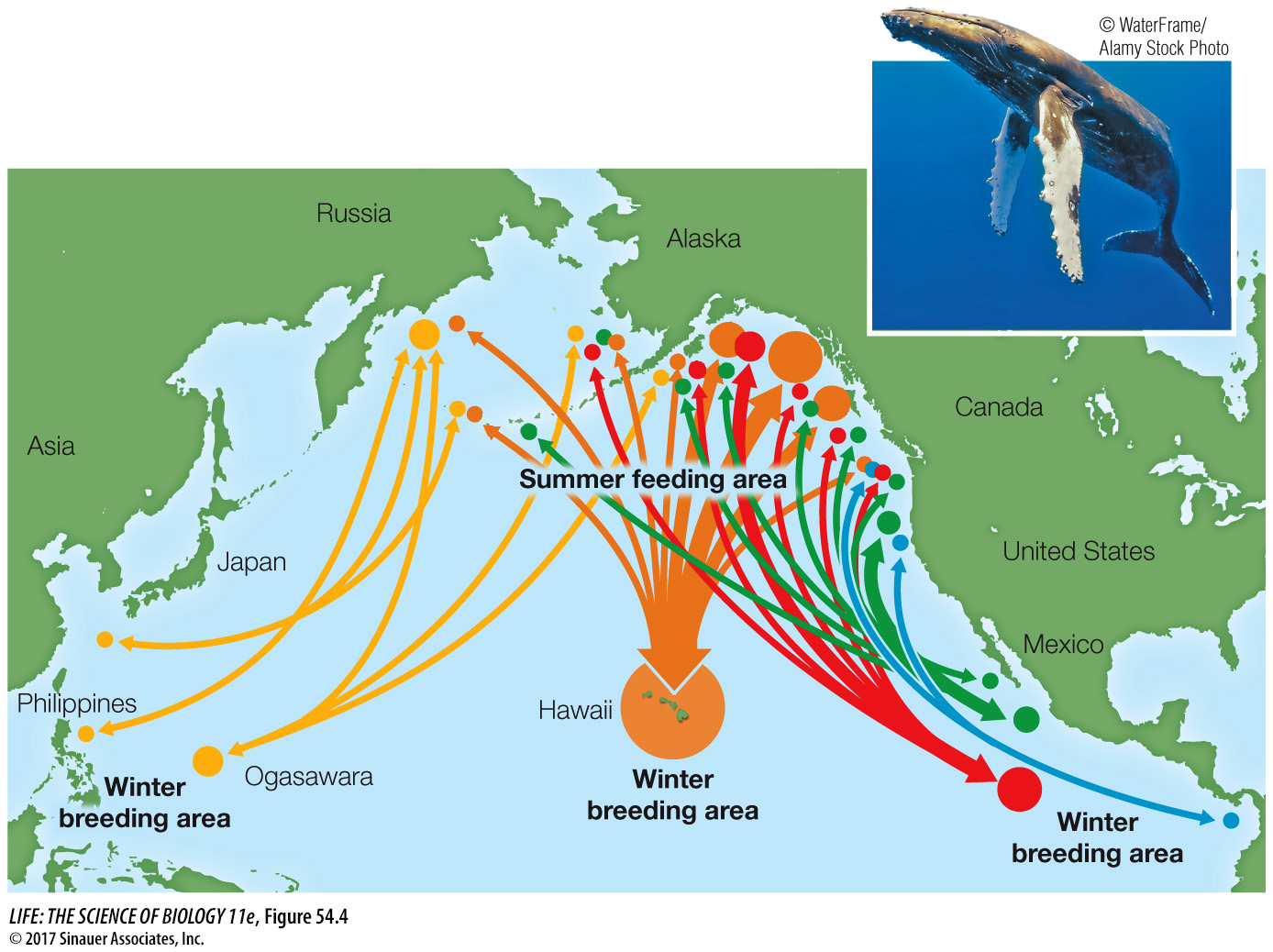

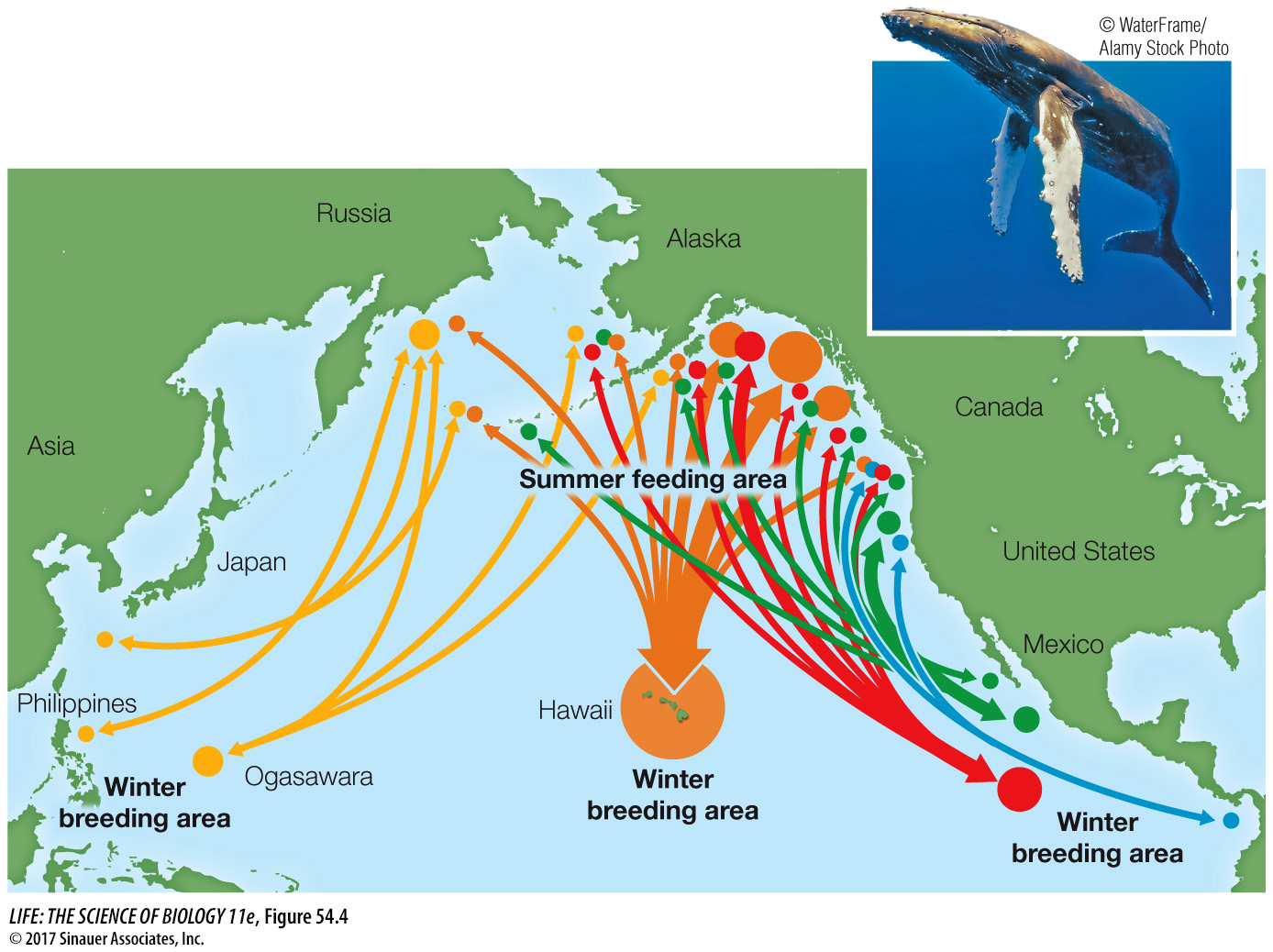

A specific type of dispersal is migration. Migration typically occurs in response to seasonal variation in resources, involves round-trip movement, and includes the whole population. For example, North Pacific populations of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) migrate more than 3,000 miles between their winter breeding grounds in the south (Mexico, Hawaii, and Japan) and their summer feeding grounds in the north (Northeast Pacific coast and Gulf of Alaska) (Figure 54.4). Scientists determine whale migration patterns and population numbers by taking photographs and collecting genetic material to follow and compare individuals in the feeding and breeding grounds. A 2006 survey of North Pacific humpback whales determined that close to 20,000 individuals in five separate populations make the migration every year. Remarkably, there were only 1,400 North Pacific humpback whales in 1966, when commercial whaling of these populations was banned.

Figure 54.4 Migration of North Pacific Humpback Whales North Pacific populations of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) migrate between their winter breeding grounds off Mexico, Hawaii, and Japan and their summer feeding grounds in the Gulf of Alaska and Northeast Pacific coast. A 2006 survey of North Pacific humpback whales determined that close to 20,000 individuals migrate in five separate populations (represented by different colored arrows).

As you can see, whale biologists use various techniques to estimate the population sizes of humpback whales. Let’s consider in more detail the variety of approaches ecologists use to measure population size.