Species interactions are not always clear-

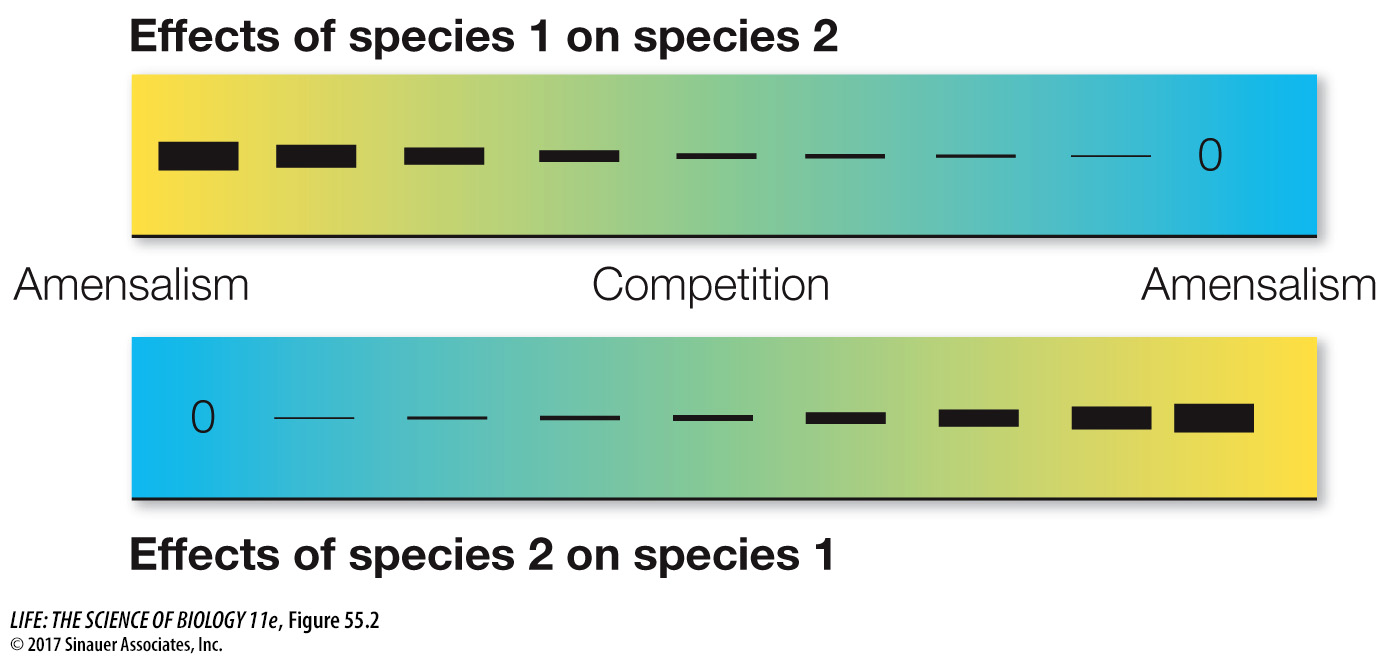

Although ecologists find it useful to classify interactions among species into a few basic categories, the boundaries between groupings are not always clear. In reality, the interaction categories described in this section are part of a continuum in how strongly each species affects the other (Figure 55.2). The continuum is a consequence of the variable strength in species interactions and their asymmetrical nature. For example, competition between the native Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) and the non-

Question

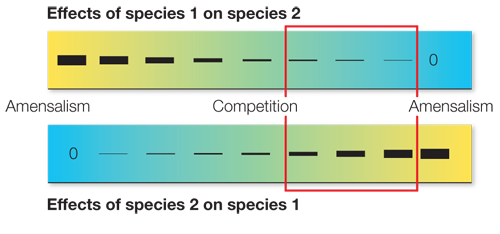

Q: Suppose the Eurasian red squirrel described in the text is species 1 and the eastern gray squirrel is species 2. Indicate which pairs of interactions between species 1 and 2 would best represent their relationship.

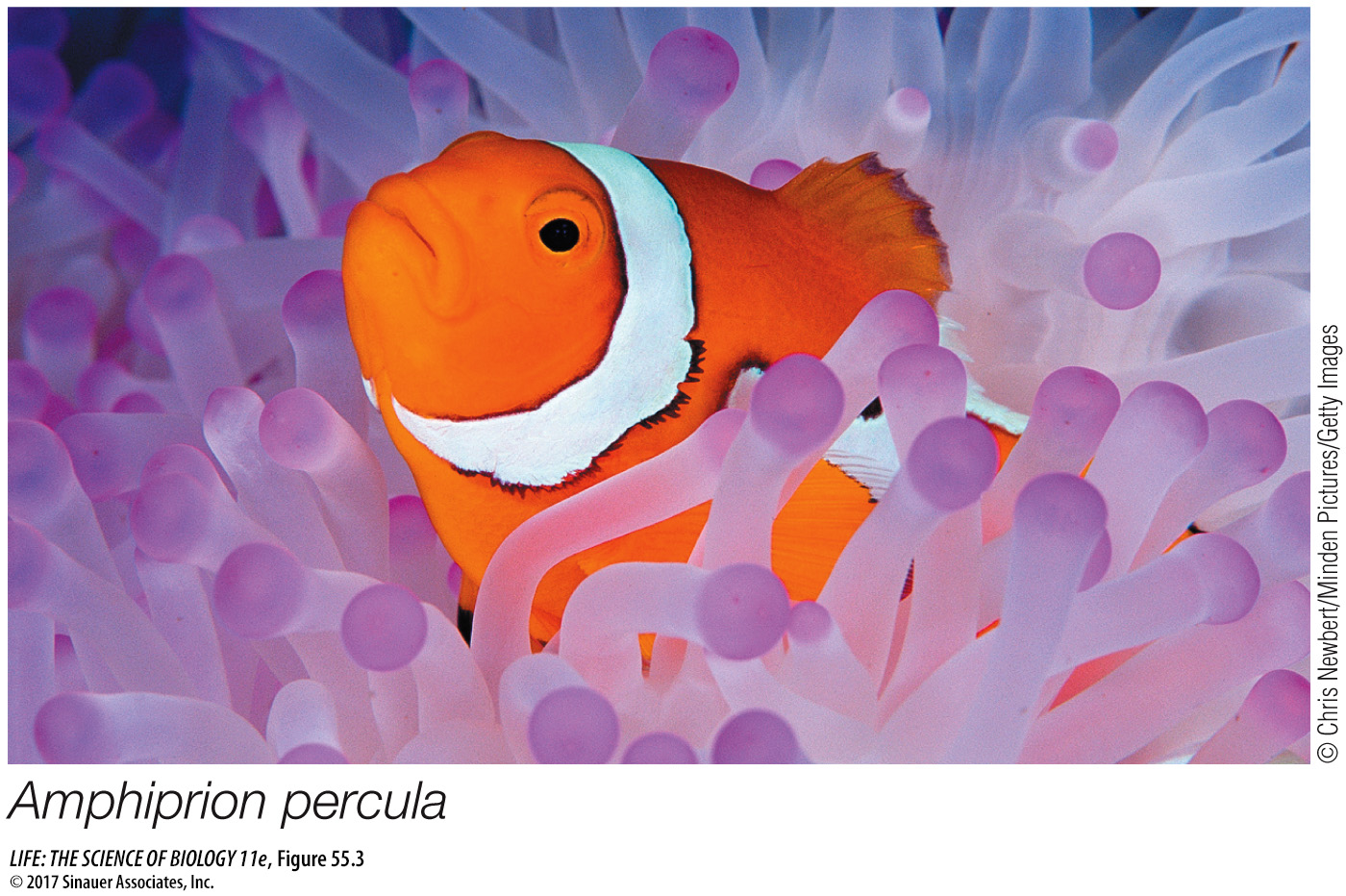

Species interactions can be difficult to classify because of the different ways in which interactions affect particular species. For example, sea anemones in the Pacific Ocean sting and eat small fish, but a select few fish species (mostly in the genus Amphiprion) live within the tentacles of sea anemones and are unaffected by their stings. Safe from its predators, an anemonefish moves freely among the stinging tentacles to scavenge the leavings of the anemone (Figure 55.3).

Anemonefish must acclimate to the anemone’s venom, and the anemone, in turn, must acclimate to the fish. The acclimation process appears to involve a change in the mucus coat of the fish; wiping off the mucus of an acclimated fish results in immediate stinging, whereas anemones do not sting fish with intact mucus. The benefits of this relationship to the anemonefish are clear: it escapes its own predators by hiding behind the anemone’s stinging tentacles, and it has no need to forage widely for food. But does the anemone benefit from the association? By defecating while in residence, the anemonefish may provide nitrogen-