Environmental conditions are critical to community membership

As you might expect, all species in a regional species pool do not end up becoming members of every community in that region. A species may make it to a community but fail to become a member because of unsuitable environmental conditions there. You might think of the influence of the environment as an “abiotic filter” that restricts species that are physiologically incapable of surviving in a given community. The lakes in the Mount St. Helens area, for example, have environmental attributes that accommodate fish, amphibians, and aquatic insects but not trees.

The physical environment can be a significant barrier to introduced non-native species. Consider, for example, marine organisms that are often introduced into foreign ports via ballast water (seawater that is pumped into and out of ballast tanks to stabilize large cargo-carrying ships). Ballast water picked up outside one port and then dumped in another can potentially release organisms (from bacteria to planktonic larvae to fish) that can colonize nearshore communities. While most ballast-water organisms do not survive the thermal, salinity, or light regimes of their new environment, a small percentage are not physiological constrained by such conditions and may gain a foothold, especially if they are introduced multiple times.

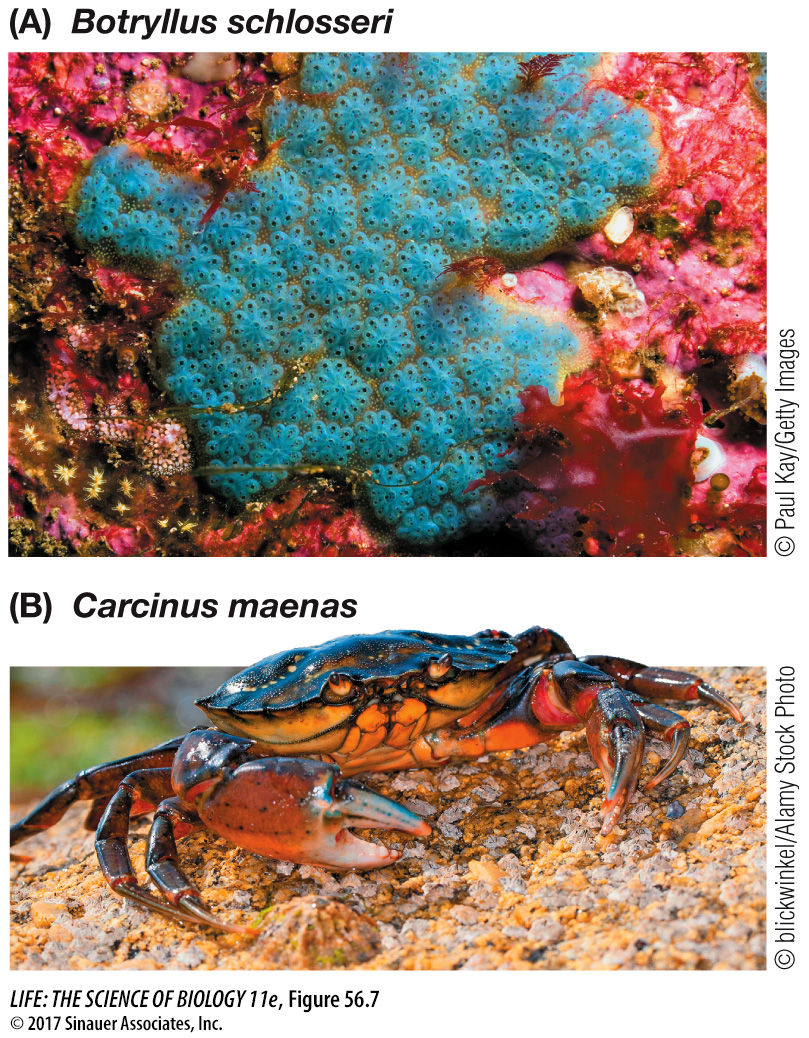

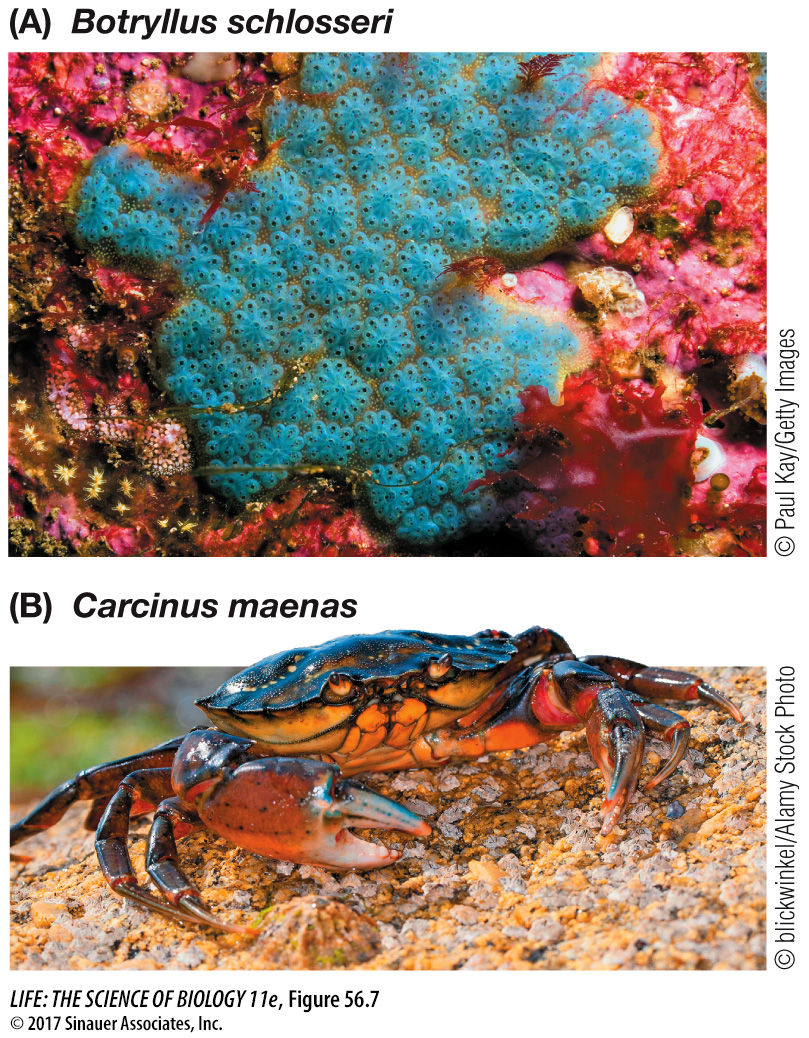

Community membership can shift with changing environmental conditions. For example, growing evidence indicates that climate change—in particular, rising temperatures—may improve conditions for some non-native species, increasing their ability to thrive. Jay Stachowicz and his colleagues found that the recruitment and growth of invasive marine invertebrates known as ascidians (sea squirts) in New England were dependent on warm winter and summer water temperatures (Figure 56.7A). Warmer temperatures gave the non-native organisms an earlier start in spring and increased the magnitude of their growth relative to that of native sea squirts. A similar story can be told for the European green crab (Carcinus maenas), whose recruitment to estuarine communities along the Pacific Northwest coast is dependent on warm water temperatures during El Niño conditions (Figure 56.7B).

Figure 56.7 Species Invasions Can Depend on Environmental Conditions (A) Invasive sea squirts in New England depend on warmer water temperatures to grow and outcompete native sea squirts. (B) The recruitment of European green crabs to Pacific Northwest estuaries depends on warm water conditions such as those during El Niño.

The final requirement for species membership is the ability to coexist with other species. Let’s consider the mediating effects of species interactions on the inclusion (or exclusion) of species in communities.