The amount of energy transferred within food webs depends on trophic efficiency

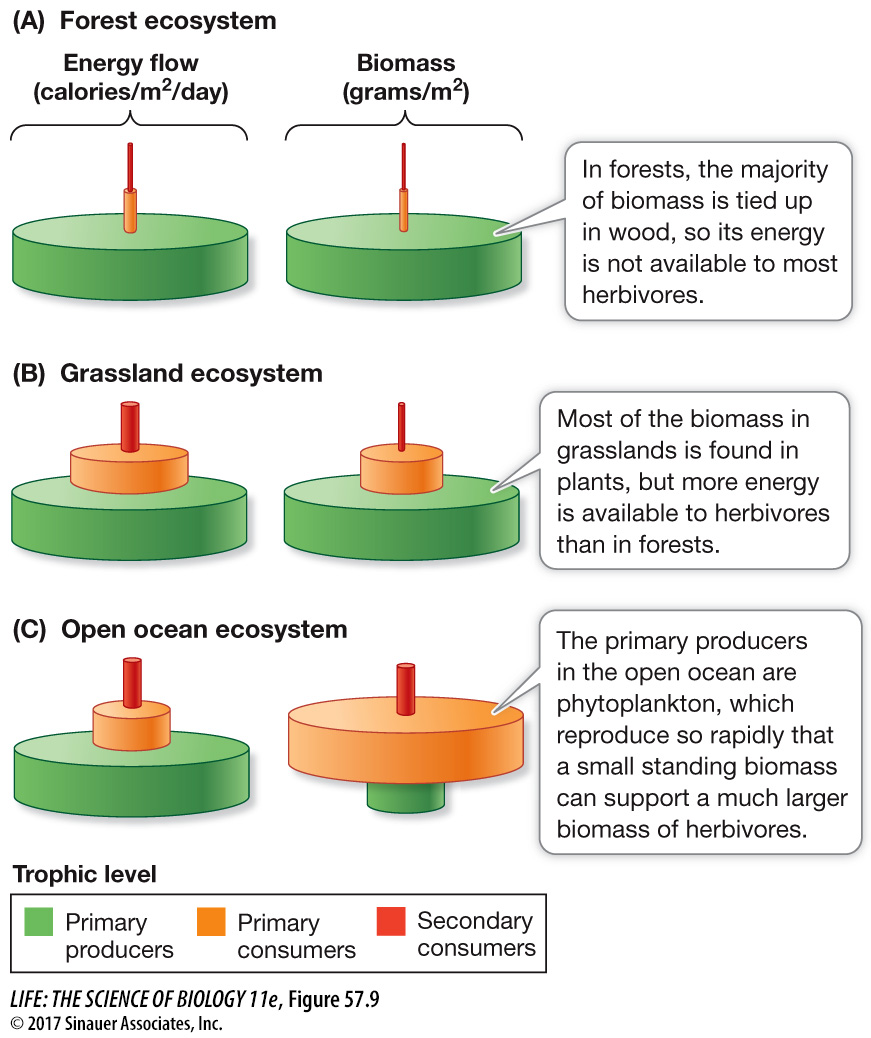

In addition to understanding how energy flows between individual consumers, we can also consider how it flows between trophic levels. Trophic efficiency is a measure of the amount of energy at one trophic level divided by the amount of energy at the trophic level immediately below it. Trophic efficiency varies among ecosystems as well as trophic levels. Pyramid diagrams such as those in Figure 57.9 illustrate the proportions of energy transferred from each trophic level to the next, making it possible to compare energy flow in different ecosystems. Pyramid diagrams can also be used to illustrate the amount of biomass found at each trophic level. As seen in Figure 57.9A and B, terrestrial ecosystems progressively lose energy from one trophic level to the next through trophic inefficiencies, especially between the primary producer and primary consumer levels. Note also that terrestrial ecosystems support less biomass at higher trophic levels than at lower trophic levels. Forest ecosystems have lower trophic efficiency than grasslands because much of the biomass in forests is in the form of wood, most of which is unavailable to primary consumers.

In aquatic systems, trophic efficiencies are much higher. Here pyramid diagrams also show a progressive loss of energy at higher trophic levels, as in terrestrial systems, but the corresponding biomass pyramids are inverted (see Figure 57.9C). Why might this be? The phytoplankton that are the primary producers in aquatic ecosystems grow and reproduce much more rapidly than do the zooplankton and small fishes that consume them, so their smaller biomass, with its rapid rate of primary production, can actually support a larger biomass of primary consumers. In part, this difference between terrestrial and aquatic systems explains why land is green but oceans are blue. Terrestrial ecosystems have primary production that far exceeds rates of herbivory, while the opposite is true for large portions of the ocean. Overall, estimates suggest that, on average, only 13 percent of terrestrial biomass is consumed by primary consumers, compared with 35 percent in aquatic ecosystems.