Protected areas preserve habitat and curtail biodiversity loss

The establishment of protected areas, in which habitat loss or degradation is restricted or prohibited, is probably the most important component of efforts to conserve and manage biodiversity. Protected areas allow populations of multiple species to maintain themselves in the preserved habitat and may also serve as nurseries from which individuals can disperse into unprotected areas, replenishing populations that might otherwise become extinct. Without proper habitat, the long-term preservation of biodiversity will be nearly impossible.

Deciding which areas to protect usually involves a complex array of decisions by stakeholders. From an ecological perspective, two criteria need to be met: (1) the candidate habitat must support viable populations of the species it is meant to protect, and (2) the original ecosystem functions and services of the candidate habitat must be mostly intact.

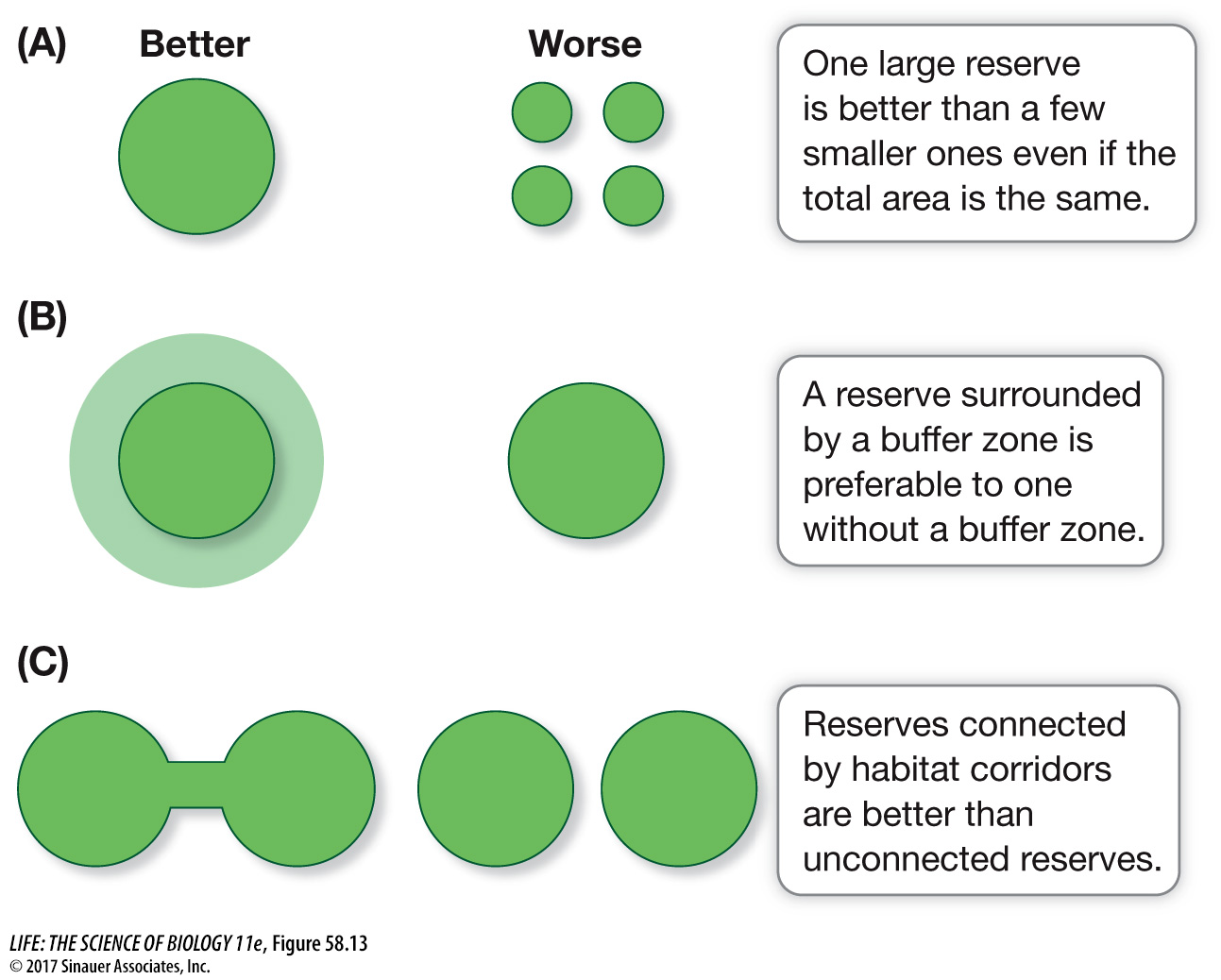

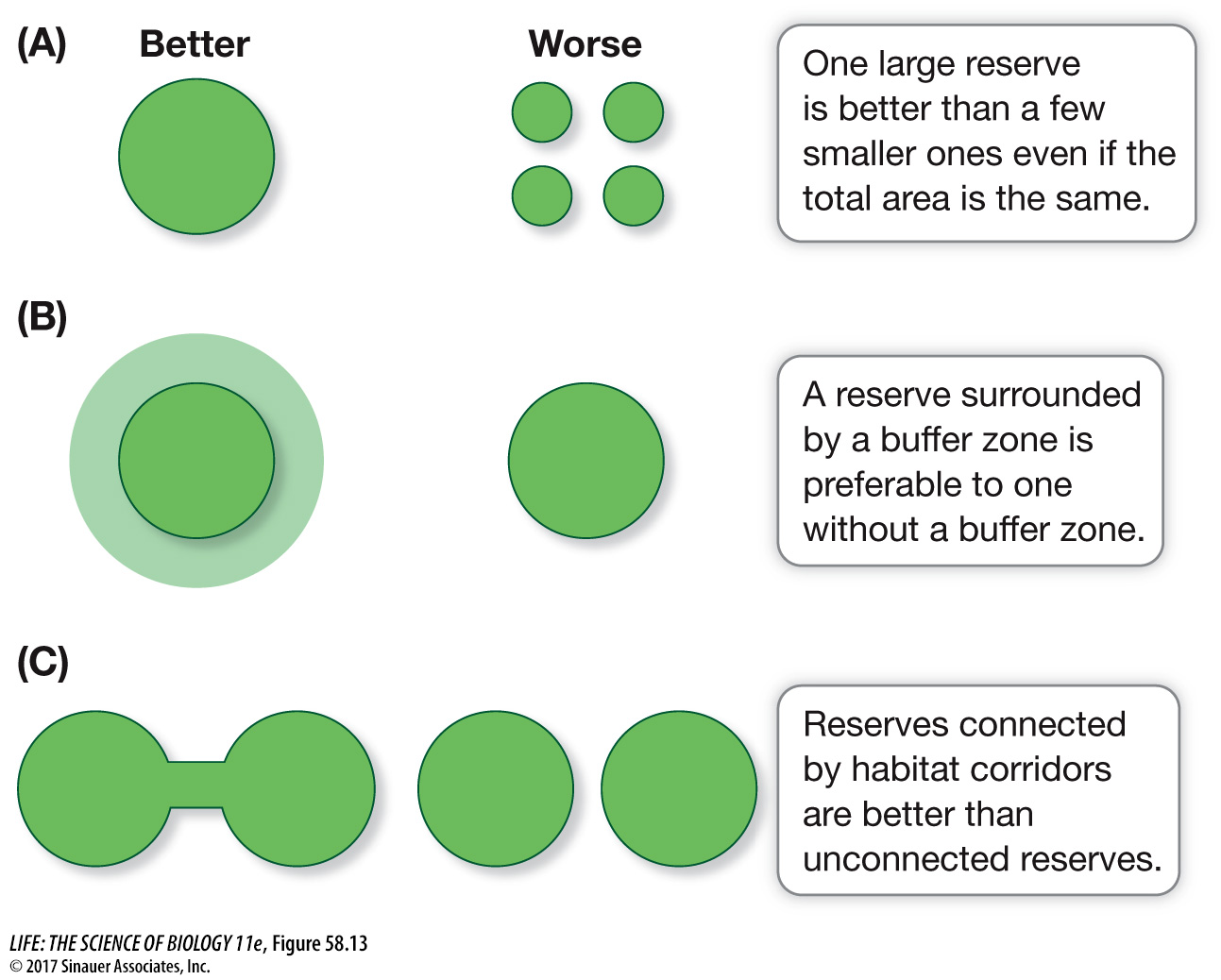

DESIGNING PROTECTED AREAS The first element in nature-preserve design involves identifying a large area that is relatively undisturbed and can serve as the core of the protected area (Figure 58.13A). This core natural area should allow populations of endangered species to maintain themselves and potentially serve as source individuals for populations outside the core area. This typically means that the core area should be large and compact with as little edge habitat as possible, to reduce edge effects.

Figure 58.13 Nature Reserve Designs Based on Ecological Principles Some spatial configurations are better than others when designing reserves for fostering biodiversity.

The second element in designing a protected area involves buffer zones around the core area (Figure 58.13B). Buffer zones have some features required by the species of concern but involve less stringent controls on land use. For example, buffer zones allow some resource extraction (e.g., timber, food, or medicines) or recreation while maintaining some of the original habitat.

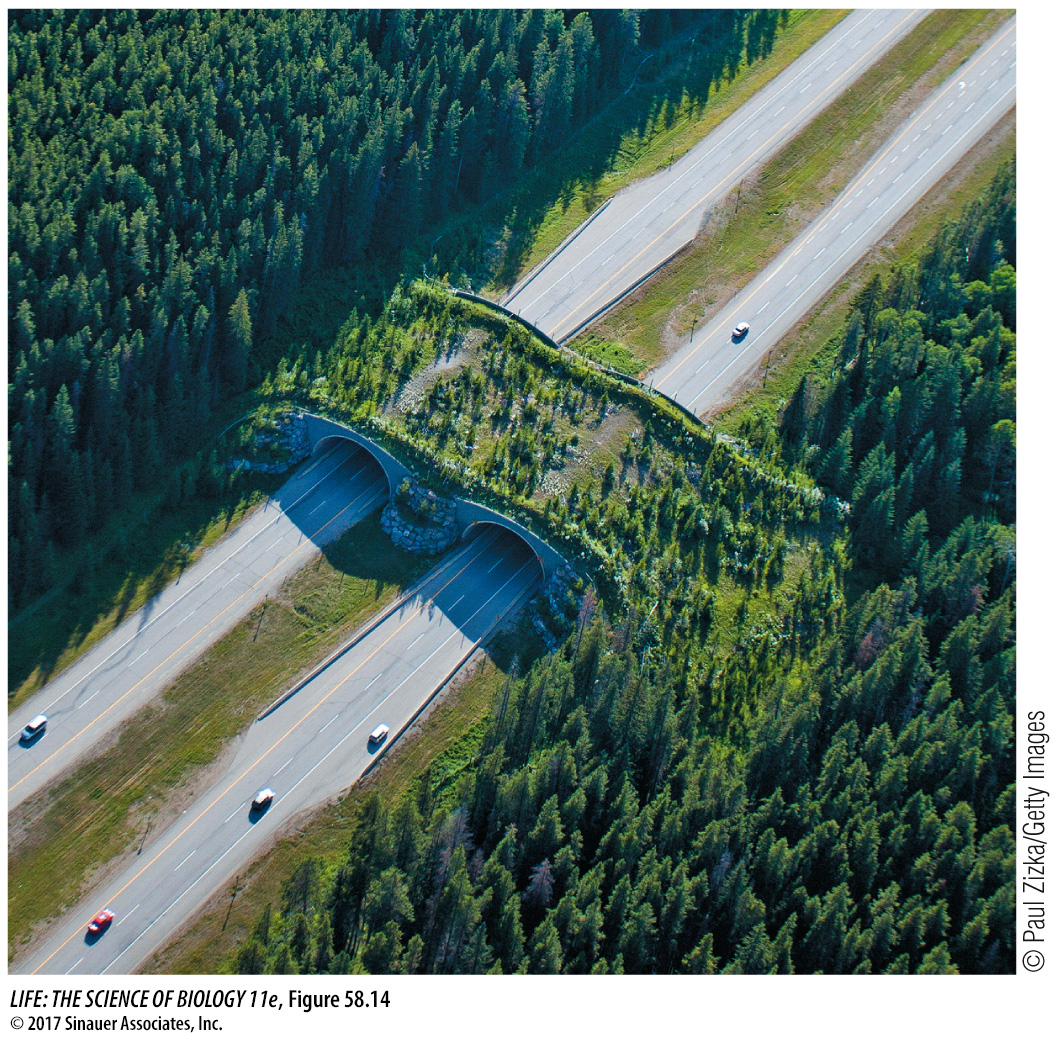

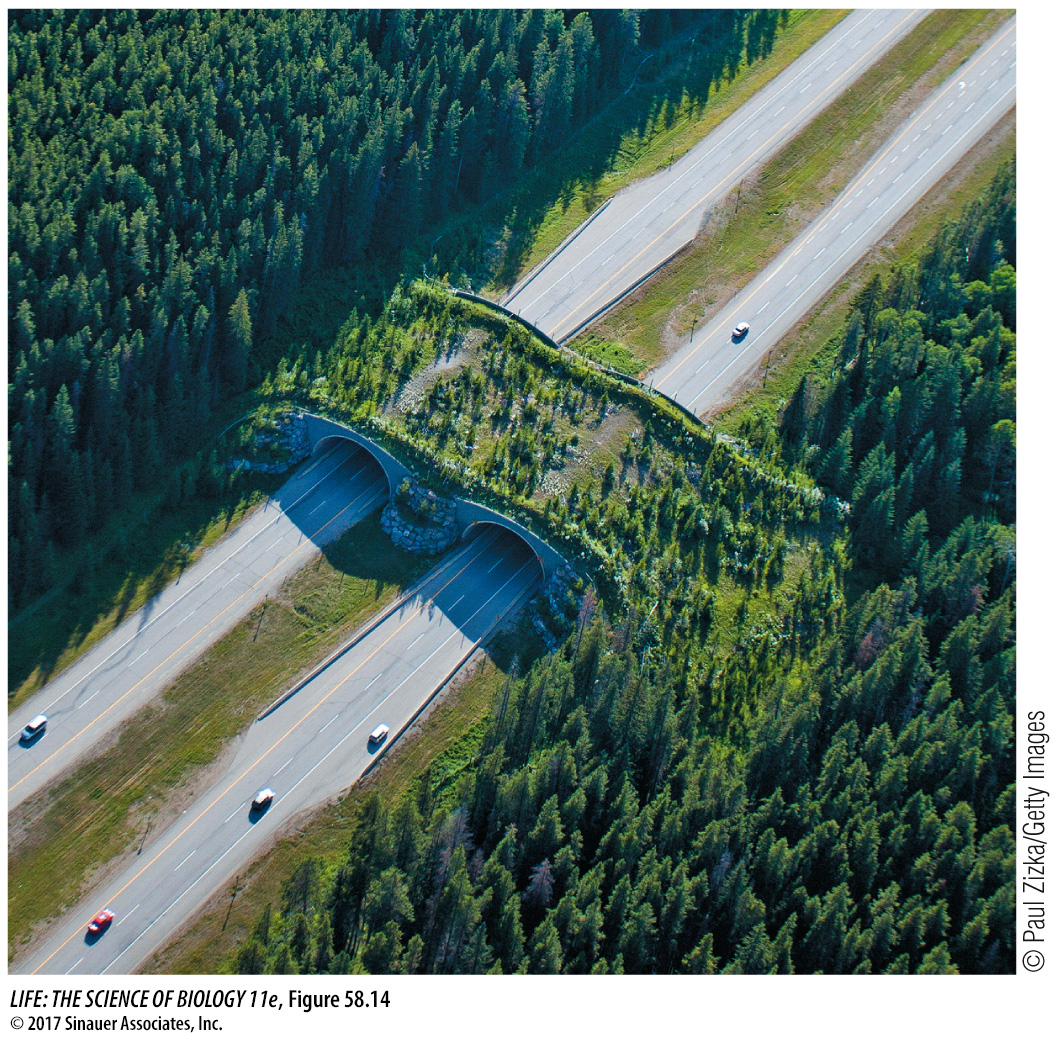

The third element in nature-preserve design involves habitat connectivity (Figure 58.13C), which keeps populations from becoming isolated from the greater metapopulation and thus subject to extinction (see Key Concept 54.4). Traveling from one protected habitat to another requires habitat corridors, or patches that connect blocks of suitable habitat. Insight into the importance of corridors has led to new regional conservation initiatives, among the most notable of which is the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. This joint Canada–United States nonprofit organization has as its goal the sustainable preservation of the mountain ecosystem extending from Yellowstone National Park in the United States to Yukon, Canada. This stretch of land, the largest intact ecosystem of its kind on the planet, contains high-quality habitat for many of North America’s most imperiled animals, including grizzly bears, gray wolves, lynx, and native fish. The initiative works with landowners to find sustainable ways of preserving high-quality, well-connected wildlife habitat in the region. For example, Banff National Park has 40 human-made corridors for wildlife that cross an 83-kilometer stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway (Figure 58.14). Managing the entire region in this way will not only provide passageways to habitat for these species, but will also provide room for their populations to shift in response to global climate change.

Figure 58.14 Habitat Corridors: Passageways to Recovery Grizzly bears and other wildlife can use this overpass to travel safely over the Trans-Canada Highway and gain access to more protected area in Banff National Park, Canada.

COUPLED HUMAN–NATURAL SYSTEMS Establishing protected areas is an essential component of efforts to maintain biodiversity, but this action alone is insufficient to stem global biodiversity loss. The extensive landscapes in which people live and extract resources should be integrated into biodiversity conservation efforts. Even urban and suburban areas can contribute to the conservation of species and habitats. The practice of encouraging biodiversity and sustainability in systems where humans and nature are intricately linked is known as coupled human–natural system ecology.

Research into coupled human–natural systems builds on the disciplines of ecology, physical sciences, social sciences, and economics. It is based on the principle that most ecosystem services are provided locally, and that people are motivated to work to protect their local interests. In practice, encouraging linkages between humans and nature comes in many forms. For example, the National Wildlife Federation has established a successful program in which people petition to have their backyards certified as wildlife-friendly. Criteria for certification include planting shrubs that provide food for birds and refraining from applying pesticides. In the case of coastal developments exposed to flooding hazards during extreme storms or sea level rise, humans are encouraging the protection and restoration of coastal wetlands and dunes, so-called green infrastructure, which provide important ecosystem services such as coastal protection, biodiversity, and recreation. Peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), once endangered by pesticide use, are thriving in urban settings where tall buildings mimic the cliffs that peregrines naturally nest on, and non-native pigeons are a main prey item. Green roofs, which are roofs covered with soil and native vegetation, are a way of creating parks and habitat, cooling buildings, and dealing with storm-water runoff, all important ecosystem services to humans. France passed a law in 2015 that requires all new buildings constructed in commercial areas to be partially covered by green roofs or solar panels.

Even some industrial sites can support biodiversity. The Turkey Point power plant in southern Florida uses large amounts of water to cool its generating units. To cool the heated water before discharging it, the Florida Power & Light Company dug a system of 38 canals that covers 2,428 hectares. These cooling canals are separated by low-lying berms that support a variety of native and non-native plants. Red mangroves grow along the edges of the canals. Today they support a thriving population of American crocodiles, a highly endangered species. Crocodiles living in the canals yield about 10 percent of all young crocodiles born in the United States.