Habitat loss and degradation endanger species

Most scientists agree that, up to this point in human history, habitat loss (reduction in habitat quantity) and habitat degradation (reduction in habitat quality) have been the major culprits in biodiversity loss. Our human footprint is large—

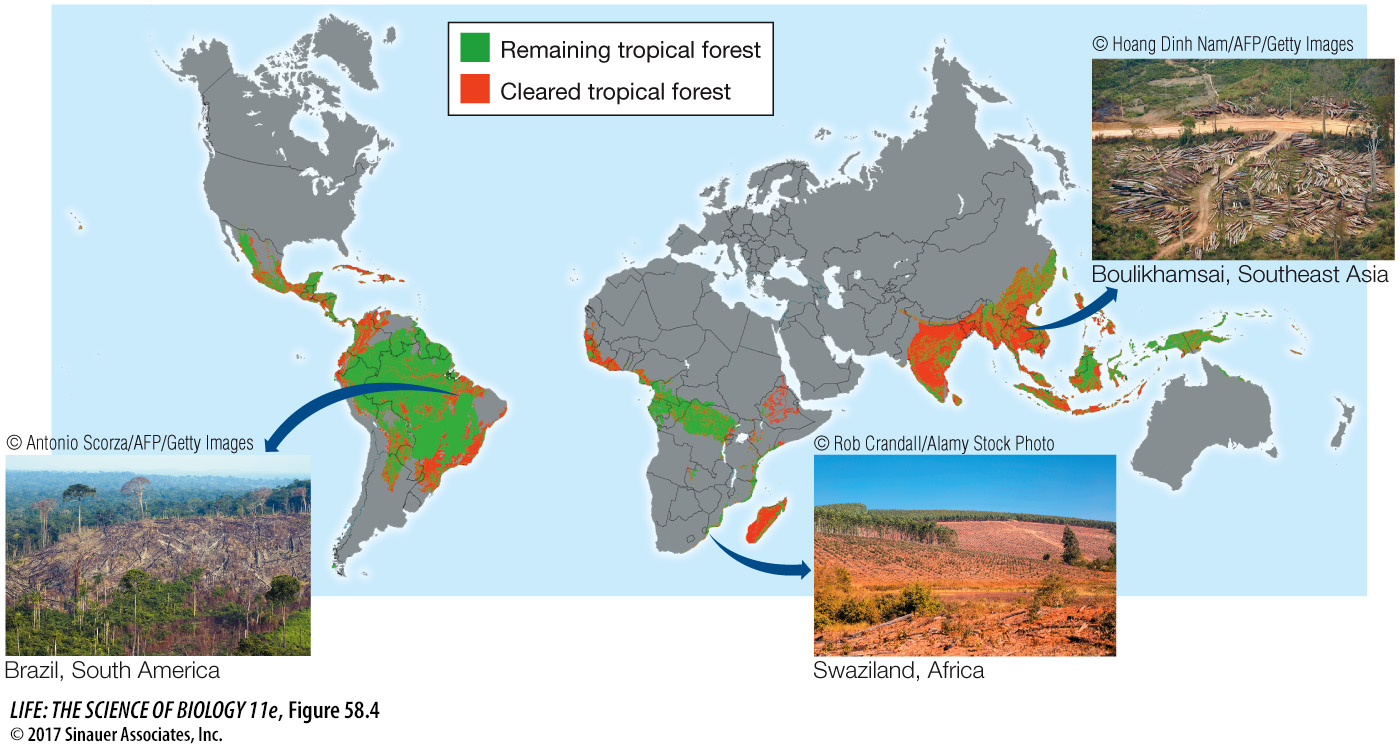

As humans increasingly dominate the planet, the transformations they are causing affect whole biomes and the species dependent on them. For example, the current rate of loss of tropical rainforest—

1254

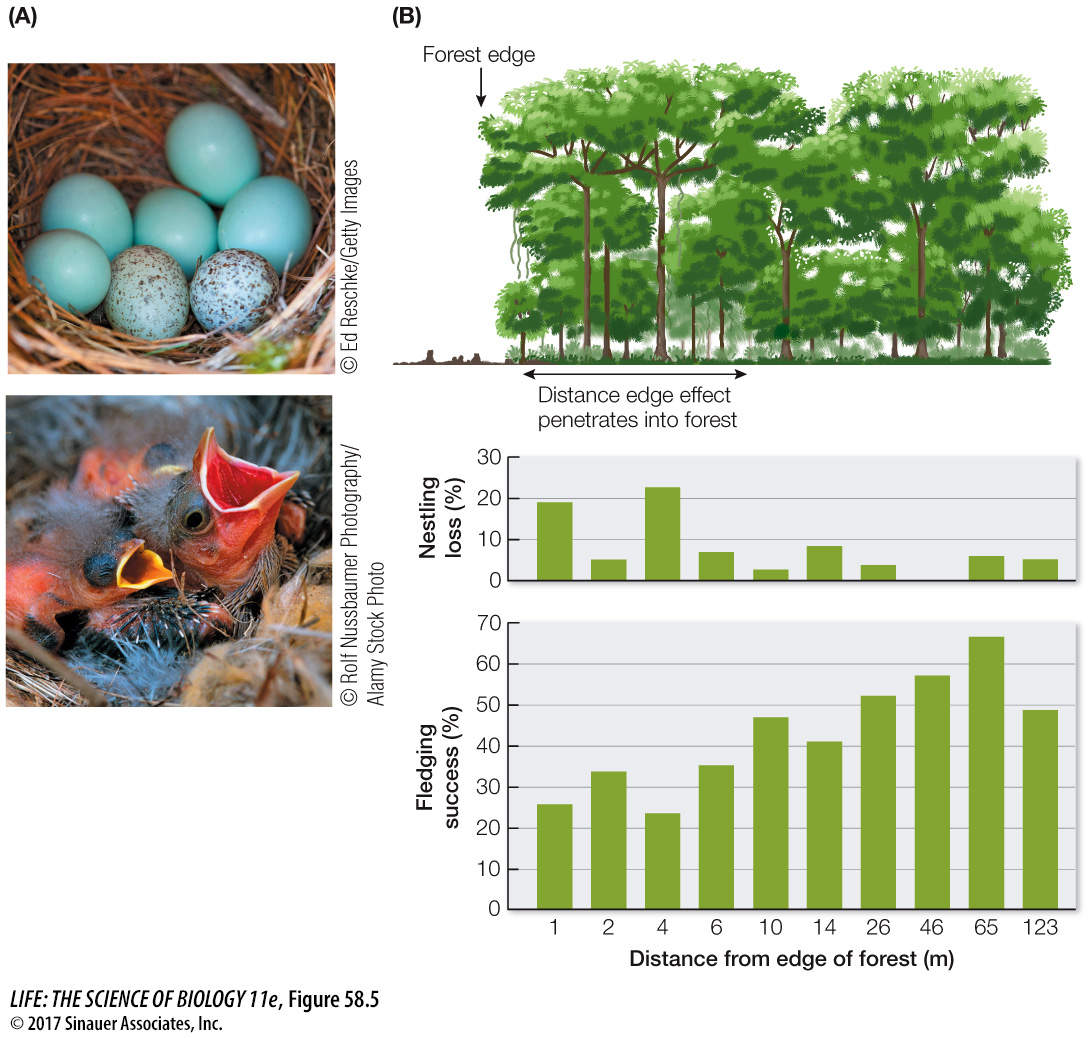

Physical destruction of habitat, as when tropical rainforests are cut down or wetlands are drained and converted to agricultural use, has significant effects on the distributions and abundances of species. Reductions in suitable habitat have contributed to the extinction of thousands of species. As the remaining habitat gets divided into smaller and smaller fragments, it can become further degraded by edge effects (as you saw in Investigating Life: The Largest Experiment on Earth in Chapter 53 and Animation 53.4, Edge Effects). Recall that as habitat fragments become smaller, proportionally more land is exposed to edge effects (see Key Concept 53.5). The physical conditions at the edges of habitats often are more similar to those of the new habitat than to the original habitat, and this can be physically stressful for species acclimated to the original habitat. In addition, species from surrounding habitats can colonize the edges, where they may compete with or prey on the species living in the fragment.

One effect of forest fragmentation in much of North America has been an increase in the abundance of the brown-

Pollution is another cause of habitat loss and degradation. The negative effects of acid rain (see Key Concept 57.4), for example, have greatly affected lake and forest ecosystems. Among the most troublesome toxic pollutants in ecosystems today are heavy metal waste products of mining and manufacturing, and synthetic organic chemicals (pesticides) released into the environment to control pests. Multiple studies have implicated a variety of pesticides in the decline of amphibian species, particularly in areas with intense agriculture such as California and the midwestern United States.

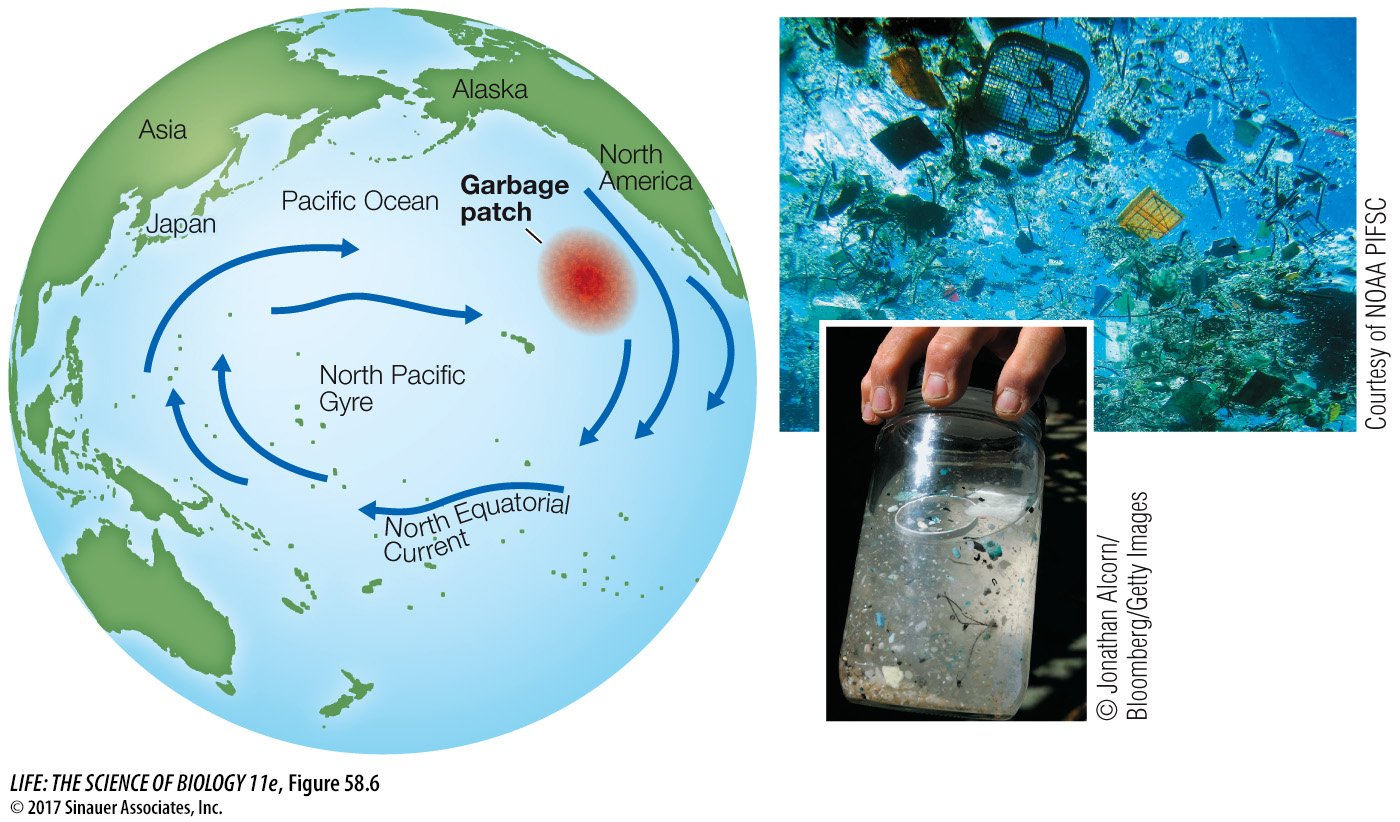

A relatively hidden form of pollution comes from nondegradable plastic garbage in open ocean habitats (Figure 58.6). One garbage patch in the middle of the Pacific Ocean is estimated to be the size of Texas. Plastic is broken up into smaller pieces and when ingested by marine birds, mammals, or fish can be a choking hazard or disrupt endocrine functions such as reproduction, neural development, and immune function. Plastic or abandoned fishing nets can also entangle marine organisms, including marine mammals, resulting in death.