George Frideric Handel, Messiah (1742)

Handel’s oratorio Messiah, his most famous work, is also one of the most famous in the whole of Western music. It is the only composition of its time that has been performed continuously — and frequently — since its first appearance. Today it is sung at Christmas and Easter in hundreds of churches around the world, as well as at symphony concerts and “Messiah sings,” where people get together just to sing along with the Hallelujah Chorus and the other well-

Unlike most oratorios, Messiah does not have actual characters depicting a biblical story in recitative and arias, although its text is taken from the Bible. In a more typical Handel oratorio, such as Samson, for example, Samson sings an aria about his blindness and argues with Delilah in recitative, while choruses represent the People of Israel and the Philistines. Instead, Messiah works with a group of anonymous narrators, relating episodes from the life of Jesus in recitative. The narration is interrupted by anonymous commentators who react to each of the episodes by singing recitatives and arias.

All this is rather like an opera in concert form; but in addition, the chorus has a large and varied role to play. On one occasion, it sings the words of a group of angels who actually speak in the Bible. Sometimes it comments on the story, like the soloists. And often the choristers raise their voices to praise the Lord in Handel’s uniquely magnificent manner.

The first two numbers in Messiah we examine cover the favorite Christmas story in which an angel announces Christ’s birth to the shepherds in the fields. Included are a recitative in four brief sections and a chorus.

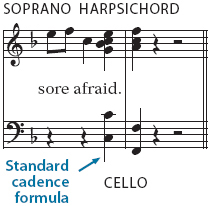

Recitative Part 1 (secco) Sung by a boy soprano narrator accompanied by continuo (cello and organ), this recitative has the natural, proselike flow typical of all recitatives. Words that would be naturally stressed in ordinary speech are brought out by longer durations, higher pitches, and pauses: “shepherds,” “field,” “flock,” and “night.” As is typical in recitative, but unlike aria, no words are repeated.

Part 2 (accompanied) Accompanied recitative is used for special effects in operas and oratorios — here the miraculous appearance of the angel. The slowly pulsing high-

Part 3 (secco) Notice that the angel speaks in a more urgent style than the narrator. And in Part 4 (accompanied), the excited, faster pulsations in the high strings depict the beating wings, perhaps, of the great crowd of angels. When Handel gets to what they will be saying, he brings the music to a triumphant high point, once again over the standard recitative cadence.

Chorus, “Glory to God” “Glory to God! Glory to God in the highest!” sing the angels — the high voices of the choir, in a bright marchlike rhythm. They are accompanied by the orchestra, with the trumpets prominent. The low voices alone add “and peace on earth,” much more slowly. Fast string runs following “Glory to God” and slower reiterated chords following “and peace on earth” recall the fast and slow string passages in the two preceding accompanied recitatives.

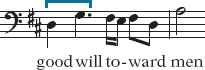

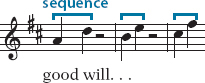

After these phrases are sung and played again, leading to another key, the full chorus sings the phrase “good will toward men” in a fugal style. The important words are good will, and their two-

The whole chorus is quite concise, even dramatic; the angels do not stay long. At the very end, the orchestra gets quieter and quieter — a rare effect in Baroque music, here indicating the disappearance of the shepherds’ vision.

LISTEN

Handel, Messiah, Recitative “There were shepherds” and Chorus “Glory to God”

| Bold italic type indicates accented words or syllables. Italics indicate phrases of text that are repeated. | ||

| RECITATIVE PART 1 (secco) | ||

| 0:01 | There were shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. | |

| PART 2 (accompanied) | ||

| 0:22 | And lo! the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them; and they were sore afraid. | Standard cadence |

| PART 3 (secco) | ||

| 0:42 | And the angel said unto them: Fear not, for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. | Standard cadence |

| For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. | Standard cadence | |

| PART 4 (accompanied) | ||

| 1:39 | And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God, and saying: | Standard cadence |

| CHORUS | ||

| 1:51 | Glory to God, glory to God, in the highest, and peace on earth, | |

| 2:30 | good will toward men good will | |

| 2:48 | Glory to God | |

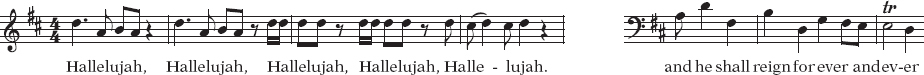

Hallelujah Chorus This famous chorus brings Act II of Messiah to a resounding close. Like “Glory to God,” “Hallelujah” makes marvelous use of monophony (“King of Kings”), homophony (the opening “Hallelujah”), and polyphony (“And he shall reign for ever and ever”); it is almost a textbook demonstration of musical textures. Compare “and peace on earth,” “Glory to God,” and “good will toward men” in the earlier chorus.

In a passage beloved by chorus singers, Handel sets “The Kingdom of this world is become” on a low descending scale, piano, swelling suddenly into a similar scale in a higher register, forte, for “the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ” — a perfect representation of one thing becoming another thing, similar but newly radiant. Later the sopranos (cheered on by the trumpets) solemnly utter the words “King of Kings” on higher and higher long notes as the other voices keep repeating their answer, “for ever, Hallelujah!”

George II of England, attending the first London performance of Messiah, was so moved by this chorus that he stood up in his box — prompting everyone else to stand — honoring the King of Kings, no doubt, but also reminding everyone of his own majesty, which was being acclaimed by the typical Baroque festive orchestra. Audiences still stand during the Hallelujah Chorus.

LISTEN

Handel, Messiah, Hallelujah Chorus

| Italics indicate phrases of text that are repeated. | |

| 0:06 | Hallelujah, Hallelujah! |

| 0:23 | For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth. Hallelujah! |

| For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth. | |

| 1:09 | The Kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ. |

| 1:26 | And He shall reign for ever and ever, and he shall reign for ever and ever. |

| 1:48 | KING OF KINGS for ever and ever, Hallelujah! |

| AND LORD OF LORDS for ever and ever, Hallelujah! | |