Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Don Giovanni (1787)

“On Monday the 29th the Italian opera company gave the eagerly awaited opera by Maestro Mozard, Don Giovanni, or The Stone Guest. Connoisseurs and musicians say that Prague had never heard the like. Herr Mozard conducted in person; when he entered the orchestra he was received by three-

Prague newspaper, 1787

Mozart wrote Don Giovanni in 1787 for Prague, the second-

Background Don Giovanni is the Italian name for Don Juan, the legendary Spanish libertine. The tale of his endless escapades and conquests is meant to stir up incredulous laughter, usually with a bawdy undertone. Certainly a subject of this kind belongs to opera buffa.

But in his compulsive, completely selfish pursuit of women, Don Giovanni ignores the rules of society, morality, and God. Hence the serious undertone of the story. He commits crimes and mortal sins — and not only against the women he seduces. He kills the father of one of his victims, the Commandant, who surprises Giovanni struggling with his daughter.

This action finally brings Don Giovanni down. Once, when he is hiding from his pursuers in a graveyard — and joking blasphemously — he is reproached by the marble statue that has been erected over the Commandant’s tomb. (Yes, the statue speaks.) He arrogantly invites the statue home for dinner. The statue comes, and when Giovanni refuses to mend his ways drags him off to its home, which is hell. The somber music associated with the statue was planted ahead of time by Mozart in the orchestral overture to Don Giovanni, before the curtain rises.

Thanks to Mozart’s music, our righteous satisfaction at Don Giovanni’s end is mixed with a good deal of sympathy for his verve and high spirits, his bravery, and his determination to live by his own rules, not those of society, even if this dooms him. The other characters in the opera, too, awaken ambivalent feelings. They amuse us and move us at the same time.

Act I, scene iii A chorus of peasants is celebrating the marriage of Masetto and Zerlina. Don Giovanni enters with his manservant Leporello and immediately spots Zerlina. He promises Masetto various favors, and then tells him to leave — and tells Leporello to take him away by force if need be.

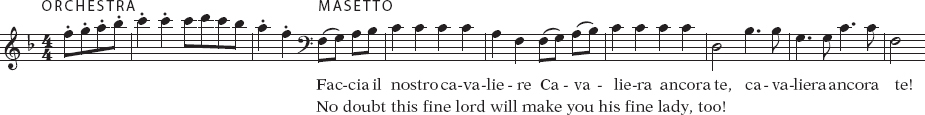

Aria, “Ho capito” This opera buffa aria, sung by Masetto, shows how vividly (and rapidly!) Mozart could define character in music. Singing almost entirely in very short phrases, Masetto almost insolently tells Don Giovanni that he will leave only because he has to; great lords can always bully peasants. Then he rails at Zerlina in furious, fast asides. She has always been his ruin! He sings a very sarcastic little tune, mocking Don Giovanni’s promise that he is going to make her into a fine lady:

Toward the end of the aria he forgets Don Giovanni and the opening music he used to address him, and thinks only of Zerlina, repeating his furious words to her and their sarcastic tune. He gets more and more worked up as he sings repeated cadences, so characteristic of the Classical style. A variation of the tune, played by the orchestra, ends this tiny aria in an angry rush.

The total effect is of a simple man (judging from the music he sings) who nonetheless feels deeply and is ready to express his anger. There is also a clear undercurrent of class conflict: Masetto the peasant versus Don Giovanni the aristocrat. Mozart was no political radical, but he himself had rebelled against court authority; and the previous opera he had written, The Marriage of Figaro, was based on a notorious French play that had been banned because of its anti-

Recitative Next comes an amusing secco recitative, sung with just continuo accompaniment, as in Baroque opera (see page 137). The dialogue moves forward quickly, as the words are sung in speechlike, conversational rhythms. Giovanni invites Zerlina up to his villa, promising to marry her and make her into a fine lady, just as Masetto had ironically predicted.

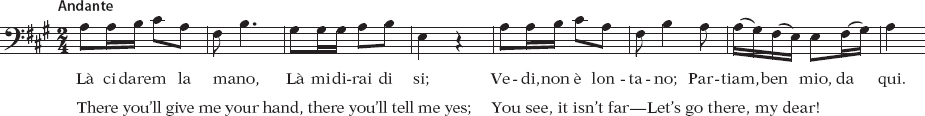

Duet, “Là ci darem la mano” Operas depend on memorable tunes, as well as on musical drama. The best opera composers write melodies that are not only beautiful in themselves but also further the drama at the same time. Such a one is the most famous tune in Don Giovanni, in the following duet (an ensemble for two singers) between Don Giovanni and Zerlina.

Section 1 (Andante) The words of this section fall into three stanzas, which the music accommodates in an A A′ B A″ coda form. Don Giovanni sings the first stanza to a simple, unforgettable tune (A) that combines seductiveness with a delicate sense of banter:

When Zerlina sings the same tune to the second stanza (A′), we know she is playing along, even though she hesitates (notice her tiny rhythmic changes and her reluctance to finish the tune as quickly as Giovanni — she stretches it out for two more measures).

In stanza 3 (B), Don Giovanni presses more and more ardently, while Zerlina keeps drawing back. Her reiterated “non son più forte” (“I’m weakening”) makes her sound very sorry for herself, but also coy. But when the main tune comes back (A″), repeating words from earlier, Giovanni and Zerlina share it phrase by phrase. Their words are closer together than before, and the stage director will place them physically closer together, too.

“17 MAY 1788. To the Opera. Don Giovanni. Mozart’s music is agreeable and very varied.”

Diary of a Viennese opera buff, Count Zinzendorf

Section 2 (Allegro) Zerlina falls into Don Giovanni’s arms, echoing his “andiam” (“let us go”). The “innocent love” they now mean to celebrate is depicted by a little rustic melody (Zerlina is a peasant girl, remember) in a faster tempo. But a not-

How neatly and charmingly an operatic ensemble can project dramatic action; this whole duet leads us step by step through Don Giovanni’s seduction line, and shows us Zerlina wavering before it. By portraying people through characteristic action or behavior — Don Giovanni winning another woman, Zerlina playing her own coy game — Mozart exposes their personalities as convincingly as any novelist or playwright.

LISTEN

Mozart, Don Giovanni, from Act I, scene iii

| Italics indicate phrases of the text that are repeated. | ||||

| ARIA: “Ho capito” |

|

|||

| 0:03 | Masetto: (to Don Giovanni) |

Ho capito, signor, si! Chino il capo, e me ne vò Ghiacche piace a voi così Altre repliche non fò. . . . Cavalier voi siete già, Dubitar non posso affè, Me lo dice la bontà, Che volete aver per me. |

I understand you, yes, sir! I touch my cap and off I go; Since that’s what you want I have nothing else to say. After all, you’re a lord, And I couldn’t suspect you, oh no! You’ve told me of the favors You mean to do for me! |

|

| 0:31 | (aside, to Zerlina) | (Briconaccia! malandrina! Fosti ognor la mia ruina!) |

(You wretch! you witch! You have always been my ruin!) |

|

| (to Leporello) | Vengo, vengo! | Yes, I’m coming — | ||

|

0:46 |

(to Zerlina) | (Resta, resta! È una cosa molto onesta; Faccia il nostro cavaliere cavaliera ancora te.) |

(Stay, why don’t you? A very innocent affair! No doubt this fine lord Will make you his fine lady, too!) |

|

| (last seven lines repeated) | ||||

| RECITATIVE (with continuo only) |

|

|||

| 1:37 | Giovanni: | Alfin siam liberati, Zerlinetta gentil, da quel scioccone. Che ne dite, mio ben, so far pulito? |

At last, we’re free, My darling Zerlinetta, of that clown. Tell me, my dear, don’t I manage things well? |

|

| Zerlina: | Signore, è mio marito! | Sir, he’s my fiancé! | ||

| Giovanni: | Chi? colui? vi par che un onest’ uomo Un nobil Cavalier, qual io mi vanto, Possa soffrir che qual visetto d’oro, Quel viso inzuccherato, Da un bifolcaccio vil sia strapazzato? |

Who? him? you think an honorable man, A noble knight, which I consider myself, Could suffer your pretty, glowing face, Your sweet face, To be stolen away by a country bumpkin? |

||

| Zerlina: | Ma signore, io gli diedi Parola di sposarlo. |

But sir, I gave him |

||

| Giovanni: | Tal parola Non vale un zero! voi non siete fata Per esser paesana. Un’altra sorte Vi procuran quegli occhi bricconcelli, Quei labretti sì belli, Quelle dituccie candide e odorose, Parmi toccar giuncata, e fiutar rose. |

That word Is worth nothing! You were not made To be a peasant girl. A different fate Is called for by those roguish eyes, Those beautiful little lips, These slender white, perfumed fingers, So soft to the touch, scented with roses. |

||

| Zerlina: | Ah, non vorrei — | Ah, I don’t want to — | ||

| Giovanni: | Che non voreste? | What don’t you want? | ||

| Zerlina: | Alfine Ingannata restar! Io so che raro Colle donne voi altri cavalieri Siete onesti e sinceri. |

To end up Deceived! I know it’s not often That with women you great gentlemen Are honest and sincere. |

||

| Giovanni: | È un’ impostura Della gente plebea! La nobiltà Ha dipinta negli occhi l’onestà. Orsù non perdiam tempo; in quest’istante Io vi voglio sposar. |

A slander Of the lower classes! The nobility Is honest to the tips of its toes. Let’s lose no time; this very instant I wish to marry you. |

||

| Zerlina: | Voi? | You? | ||

| Giovanni: | Certo io. Quel casinetto è mio, soli saremo; E là, gioella mio, ci sposeremo. |

Certainly, me; There’s my little place; we’ll be alone — And there, my precious, we’ll be married. |

||

| DUET: “Là ci darem la mano” |

|

|||

| SECTION 1 Andante, 2/4 meter | ||||

| 3:24 | Giovanni: | A |

Là ci darem la mano Là mi dirai di si! Vedi, non è lontano; Partiam, ben mio, da qui! |

There [in the villa] you’ll give me your hand, There you’ll tell me yes! You see, it isn’t far — Let’s go there, my dear! |

| Zerlina: | A′ | Vorrei, e non vorrei; Mi trema un poco il cor. Felice, è ver, sarei, Ma può burlarmi ancor. |

I want to, yet I don’t want to; My heart is trembling a little; It’s true, I would be happy, But he could be joking with me. |

|

| 4:09 | Giovanni: | B | Vieni, mio bel diletto! | Come, my darling! |

| Zerlina: | Mi fa pietà Masetto . . . | I’m sorry for Masetto . . . | ||

| Giovanni: | Io cangierò tua sorte! | I shall change your lot! | ||

| Zerlina: | Presto non son più forte . . . | All of a sudden I’m weakening . . . | ||

|

(repetition of phrases [both verbal and musical] from stanzas 1– |

||||

| 4:34 | Giovanni: | A″ | Vieni, vieni! Là ci darem la mano |

Don Giovanni leads Zerlina on. Jack Vartoogian/Getty Archive Photos.

|

| Zerlina: | Vorrei, e non vorrei . . . | |||

| Giovanni: | Là mi dirai di si! | |||

| Zerlina: | Mi trema un poco il cor. | |||

| Giovanni: | Partiam, ben mio, da qui! | |||

| Zerlina: | Ma può burlarmi ancor. | |||

| 5:04 | Giovanni: | coda | Vieni, mio bel diletto! | |

| Zerlina: | Mi fa pietà Masetto . . . | |||

| Giovanni: | Io cangierò tua sorte! | |||

| Zerlina: | Presto non son più forte . . . | |||

| Giovanni; then Zerlina: | Andiam! | |||

|

SECTION 2 Allegro, 6/8 meter |

||||

| 5:33 | Both: | Andiam, andiam, mio bene, A ristorar le pene D’un innocente amor. |

Let us go, my dear, And relieve the pangs Of an innocent love. |

|

| (words and music repeated) | ||||