Romanticism and Realism

European literature and art from the 1850s on was marked not by continuing Romanticism, but by realism. The novel, the principal literary genre of the time, grew more realistic from Dickens to Trollope and George Eliot in Britain, and from Balzac to Flaubert and Zola in France. In French painting, there was an important realist school led by Gustave Courbet. Thomas Eakins was a realist painter in America; William Dean Howells was our leading realist novelist. Most important as a stimulus to realism in the visual arts was that powerful new invention, the camera.

There was a move toward realism in opera at the end of the nineteenth century, as we have seen (page 274). On the other hand, the myth-drenched music dramas of Wagner were as unrealistic as could be. (Wagner thought he was getting at a deeper, psychological realism.) And what would “realism” in orchestral music be like? Given music’s nature, it was perhaps inevitable that late nineteenth-century music came to function as an inspirational and emotional escape — an escape from political, economic, and social situations that were not romantic in the least.

Perhaps, too, music serves a similar function for many listeners of the twenty-first century. Significantly, concert life as we know it today, with its emphasis on great masterpieces of the past, was formed for the first time in the late nineteenth century.

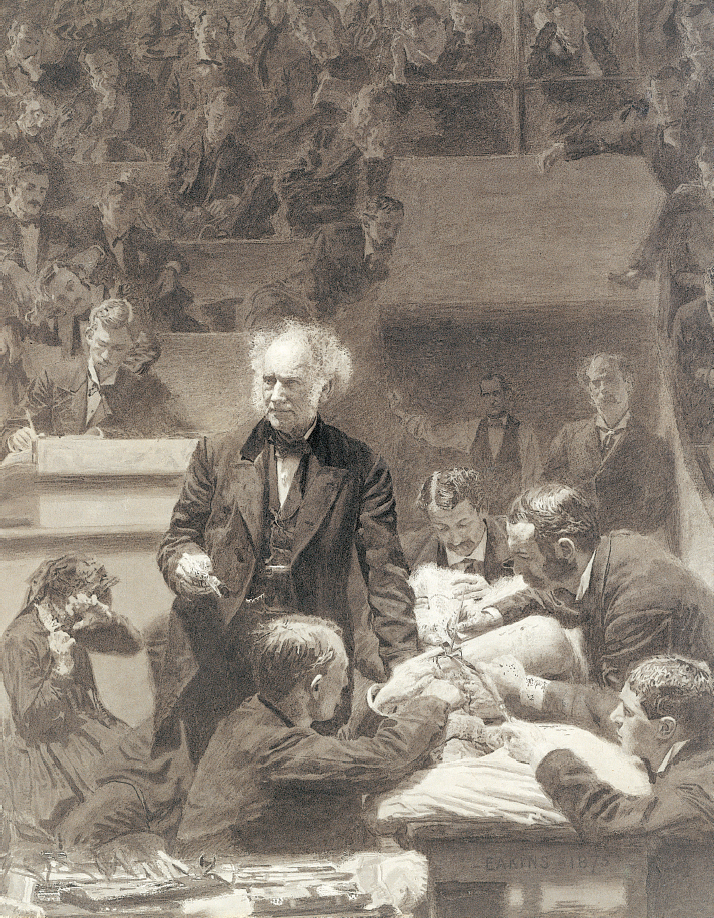

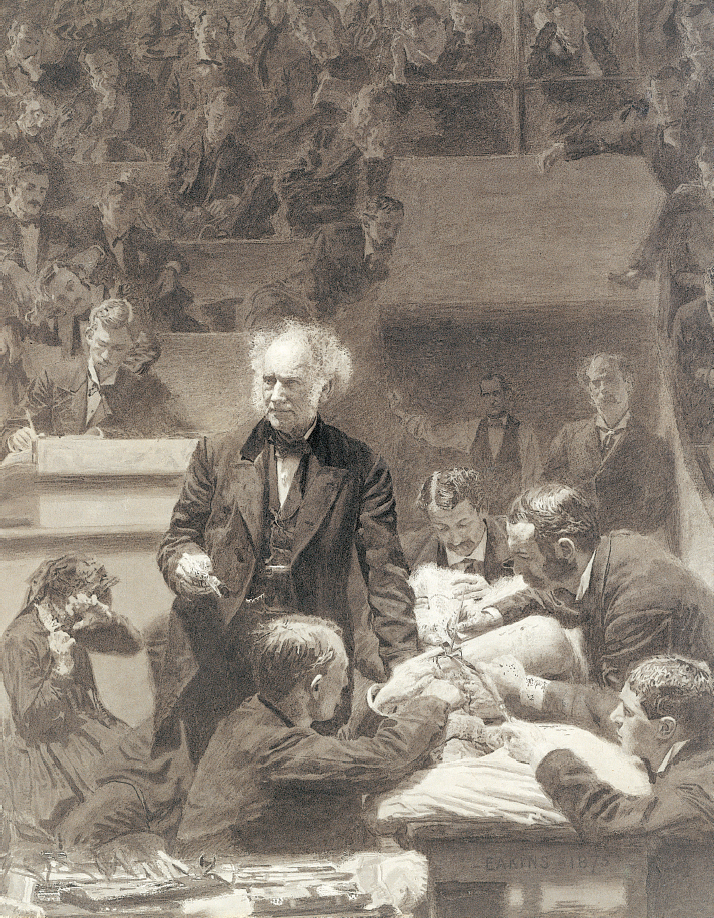

Realists in the arts of the nineteenth century tended toward glum or grim subject matter. The Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins was so fascinated by surgery that he painted himself in among the students attending a class by a famous medical professor, Dr. S. D. Gross (The Gross Clinic, 1875). The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY.