Introduction to Unit V, The Twentieth Century and Beyond

This unit covers music from around 1900 on and brings our survey up to the present. Looking back to the year 1900, we can recognize today’s society in an early form. Large cities, industrialization, inoculation against disease, mass food processing, the first automobiles, telephones, movies, and phonographs — all were in place by the early years of the twentieth century. Hence the society treated in this unit will strike us as fairly familiar, compared to the societies of earlier centuries.

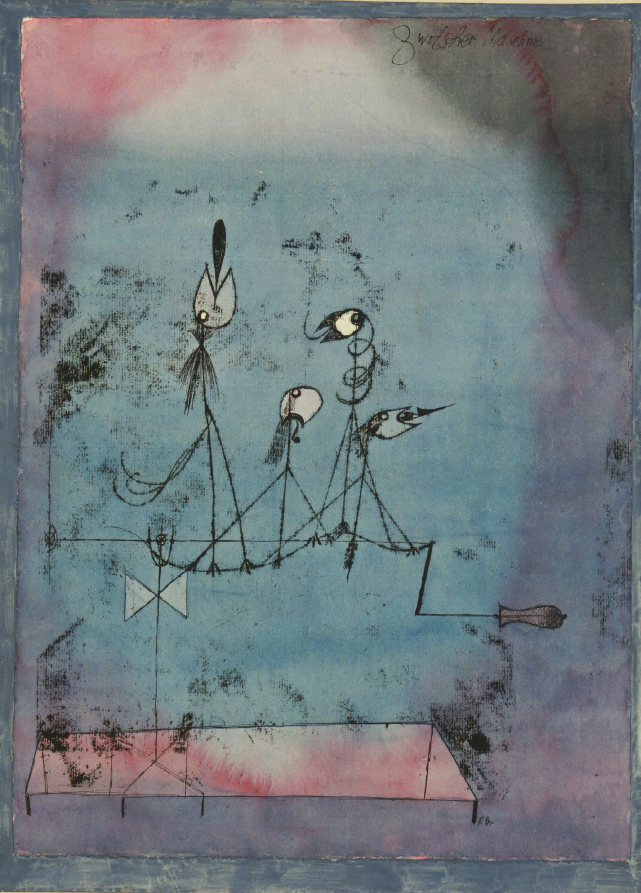

But the classical music produced in this period may strike us as anything but familiar. Around 1900, classical music experienced some of the most dramatic and abrupt changes in its entire history. Along with the changes came a wider variety of styles than ever before. At times it seemed almost as if each composer felt the need to create an entirely individual musical language. This tendency toward radical innovation, once it set in, was felt in repeated waves throughout the twentieth century. This vibrant, innovative, and unsettling creativity comes under the label “modernism.”

Another development of great importance occurred around 1900: the widening split between classical and popular music. A rift that had started in the nineteenth century became a prime factor of musical life, giving rise to new traditions of American popular music. With the evolution of ragtime and early jazz, a vital rhythmic strain derived from African American sources was brought into the general American consciousness. This led to a long series of developments: swing, bebop, rhythm and blues, rock, rap, and more.

In this unit we sample the variety of musical modernism and glimpse the movement’s outgrowths around the turn of the new millennium. The final chapter deals with America’s characteristic popular music.

Chronology

| 1899 | Debussy, Clouds | p. 313 |

| 1906 | Ives, The Unanswered Question | p. 333 |

| 1909 | Ives, Second Orchestral Set | p. 331 |

| 1912 | Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire | p. 321 |

| 1913 | Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring | p. 317 |

| 1913 | Webern, Five Orchestral Pieces | p. 362 |

| 1923 | Berg, Wozzeck | p. 324 |

| 1927 | Thomas, “If You Ever Been Down” Blues | p. 387 |

| 1928 | Crawford, Prelude for Piano No. 6 | p. 345 |

| 1930 | Still, Afro- |

p. 348 |

| 1931 | Ravel, Piano Concerto in G | p. 337 |

| 1936 | Bartók, Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta | p. 341 |

| 1938 | Prokofiev, Alexander Nevsky Cantata | p. 354 |

| 1940 | Ellington, “Conga Brava” | p. 391 |

| 1945 | Copland, Appalachian Spring | p. 350 |

| 1948 | Parker and Davis, “Out of Nowhere” | p. 395 |

| 1952 | Cage, 4’ 33” | p. 367 |

| 1957 | Bernstein, West Side Story | p. 399 |

| 1958 | Varèse, Poème électronique | p. 364 |

| 1966 | Ligeti, Lux aeterna | p. 366 |

| 1969 | Davis, Bitches Brew | p. 396 |

| 1974– |

Reich, Music for 18 Musicians | p. 369 |

| 1991 | León, Indígena | p. 375 |

| 2005 | Adams, Doctor Atomic | p. 377 |

| 2006 | Crumb, Voices from a Forgotten World (American Songbook, Volume 5) | p. 374 |