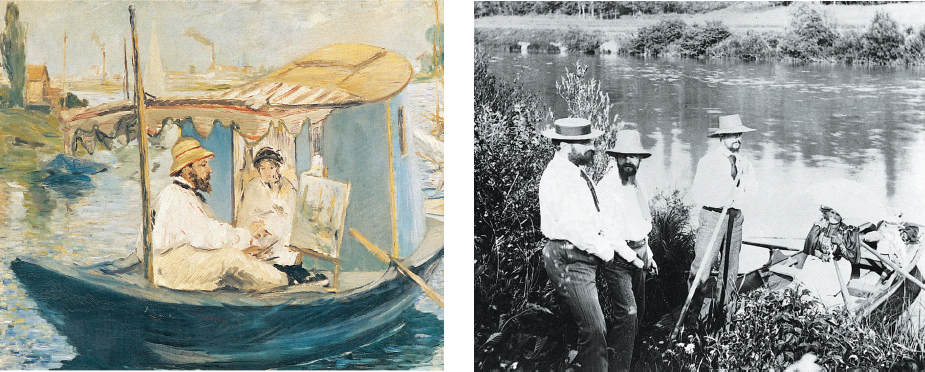

Impressionists and Symbolists

Modernism got its start in the late nineteenth century and then peaked in the twentieth. The best-

Symbolism, a consciously unrealistic movement, followed soon after impressionism. Symbolist poets revolted against the “realism” of words being used for reference — for the purpose of exact definition or denoting. They wanted words to perform their symbolizing or signifying function as freely as possible, without having to fit into phrases or sentences. The meaning of a cluster of words might be vague and ambiguous, even esoteric — but also rich, “musical,” and endlessly suggestive.

Musical was a word the symbolists liked to apply to their language. They were fascinated by the music dramas of Richard Wagner, where again musical symbols — Wagner’s leitmotivs — refer to elements in his dramas in a complex, multilayered fashion. All poets use musical devices such as rhythm and rhyme, but the symbolists were prepared to go so far as to break down grammar, syntax, and conventional thought sequence to approach the elusive, vague reference of Wagner’s music.

Those nymphs, I want to perpetuate them.

So clear

Their carnation flesh, that it flutters in the air,

Drowsy with tufted slumbers. Was it a dream I loved?

Opening of the symbolist poet

Stéphane Mallarmé’s

“The Afternoon of a Faun”

Claude Debussy is often called an impressionist in music because his fragmentary motives and little flashes of tone color seem to recall the impressionists’ painting technique. Debussy can also — and more accurately — be called a symbolist, since suggestion, rather than outright statement, is at the heart of his aesthetic. Famous symbolist texts inspired two of Debussy’s pathbreaking works: the orchestral Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” (a poemby Stéphane Mallarmé) and the opera Pelléas et Mélisande (a play by Maurice Maeterlinck). In the opera Debussy’s elusive musical symbols and Maeterlinck’s elusive verbal ones combine to produce an unforgettable effect of mysterious suggestion.