Henry Purcell, Dido and Aeneas (1689)

Though Purcell composed a good deal of music for the London theater, his one true opera, Dido and Aeneas, was performed at a girls’ school (though there may have been an earlier performance at court). The whole thing lasts little more than an hour and contains no virtuoso singing roles at all. Dido and Aeneas is an exceptional work, then, and a miniature. But it is also a work of rare beauty and dramatic power — and rarer still, it is a great opera in English, perhaps the only great opera in English prior to the twentieth century.

Background Purcell’s source was the Aeneid, the noblest of all Latin epic poems, written by Virgil to celebrate the glory of Rome and the Roman Empire. It tells the story of the city’s foundation by the Trojan prince Aeneas, who escapes from Troy when the Greeks capture it with their wooden horse. After many adventures and travels, Aeneas finally reaches Italy, guided by the firm hand of Jove, king of the gods.

In one of the Aeneid’s most famous episodes, Aeneas and the widowed Queen Dido of Carthage fall deeply in love. But Jove tells the prince to stop dallying and get on with his important journey. Regretfully he leaves, and Dido kills herself — an agonizing suicide, as Virgil describes it.

In Acts I and II of the opera, Dido expresses apprehension about her feelings for Aeneas, even though her courtiers keep encouraging the match in chorus after chorus. Next we see the plotting of some witches — a highly un-

In Act III, Aeneas tries feebly to excuse himself. Dido spurns him in a furious recitative. As he leaves, deserting her, she prepares for her suicide.

Recitative Dido addresses this regal, somber recitative to her confidante, Belinda. Notice the imperious tone as she tells Belinda to take her hand, and the ominous word painting on darkness. Purcell designed the melody of this recitative as a long, gradual descent, as if Dido’s life force is already ebbing away.

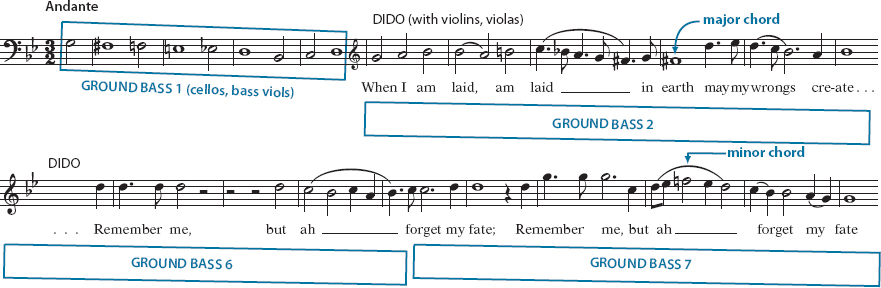

Aria The opera’s final aria, usually known as “Dido’s Lament,” is built over a slow ground bass or ostinato (see page 83), a descending bass line with chromatic semitones (half steps) repeated a dozen times. The bass line sounds mournful even without accompaniment, as in measures 1–

The most heartbreaking place comes (twice) on the exclamation “ah,” where the bass note D, harmonized with a major-

Chorus The last notes of this great aria run into a wonderful final chorus. We are to imagine a slow dance, as groups of sorrowful cupids (first graders, perhaps) file past the bier. Now Dido’s personal grief and agony are transmuted into a sense of communal mourning. In the context of the whole opera, this chorus seems even more meaningful, because the courtiers who sing it have matured so much since the time when they thoughtlessly and cheerfully urged Dido to give in to her love.

The general style of the music is that of the madrigal — imitative polyphony and homophony, with some word painting. (The first three lines are mostly imitative, the last one homophonic.) But Purcell’s style clearly shows the inroads of functional harmony and of the definite, unified rhythms that had been developing in the seventeenth century. There is no mistaking this touching chorus for an actual Renaissance madrigal.

Like “Dido’s Lament,” “With drooping wings” is another emotional tableau, and this time the emotion spills over to the opera audience. As the courtiers grieve for Dido, we join them in responding to her tragedy.

LISTEN

Purcell, Dido and Aeneas, Act III, final scene

| Italics indicate repeated words and lines. Colored type indicates words treated with word painting. | |||

| RECITATIVE | |||

| 0:00 | Dido: |

Thy hand, Belinda! Darkness shades me; On thy bosom let me rest. More I would — but death invades me: Death is now a welcome guest. |

|

| ARIA | |||

| 0:58 | Dido: |

When I am laid in earth May my wrongs create No trouble in thy breast; (repeated) |

|

| 2:17 |

Remember me, but ah, forget my fate; Remember me, but ah, forget my fate. (stabs herself) |

||

| CHORUS |

|

||

| 0:00 | Courtiers: |

With drooping wings, ye cupids come And scatter roses on her tomb. Soft, soft and gentle as her heart. |

|

| 1:30 |

Keep here your watch; Keep here your watch, and never part. |

||