Classic Experiment 19-1: How Cyclins Were Discovered

How Cyclins Were Discovered

T. Evans et al., 1983, Cell 33:391

From the first cell divisions after fertilization to the aberrant divisions that occur in cancers, biologists have long been interested in how cells control when they divide. While studying early development in marine invertebrates in the early 1980s, Joan Ruderman and Tim Hunt discovered the cyclins, key regulators of the cell cycle.

Background

The question of how an organism develops from a fertilized egg continues to drive a large body of scientific research. Whereas such research was classically the concern of embryologists, the developing understanding of gene expression in the 1980s brought new approaches to this question. One such approach was to examine the patterns of gene expression in the oocyte and in the newly fertilized egg. Ruderman and Hunt were among the biologists who took this approach to the study of early development.

By this time, the early development of a number of marine invertebrate model systems had been well characterized. Their eggs are fertilized externally, which allows researchers to study their development in a plastic dish. During the early stages of development, the embryonic cells divide synchronously, which allows an entire population of cells to be studied at the same stage of the cell cycle. Researchers had established that a large proportion of the mRNAs in the unfertilized oocyte are not translated. Upon fertilization, these maternal mRNAs are rapidly translated. Previous studies had shown that when fertilized eggs were treated with drugs that inhibit protein synthesis, cell division could not take place. This finding suggested that the initial burst of protein synthesis from the maternal mRNA is required at the earliest stages of development. Ruderman and Hunt, while teaching a physiology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, began a set of experiments designed to uncover the genes that were expressed at this point as well as the mechanism by which this burst of protein synthesis was controlled.

The Experiment

In a collaborative project, Ruderman and Hunt looked at regulation of gene expression in the fertilized egg of the surf clam Spisula solidissima. Whereas it was known that overall protein synthesis increased rapidly upon fertilization, they wanted to find out whether the proteins expressed in the earliest stage of development, the two-

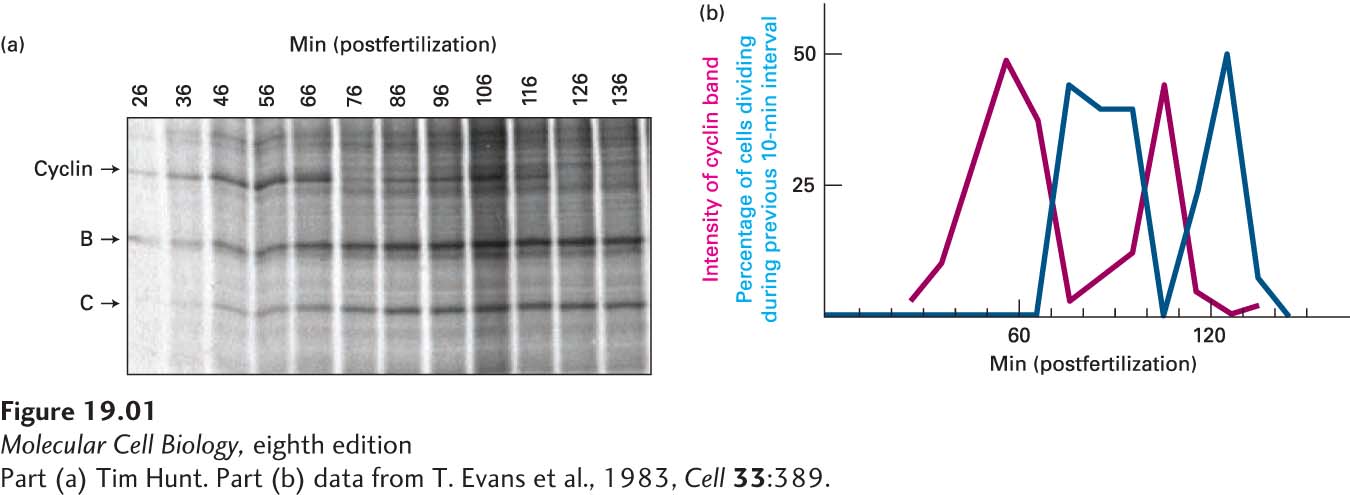

Soon afterward, in a third study, Hunt examined changes in protein expression during the maturation and fertilization of sea urchin oocytes (Evans et al., 1983). This time he performed the experiment in a slightly different manner. Rather than treating oocytes and embryos with radioactively labeled amino acids for a set time period, he treated the cells continuously for more than 2 hours, removing samples for analysis at 10-

Because the time frame of the experiment coincided with early embryonic cell divisions, Hunt next asked whether the synthesis and destruction of the protein was correlated with progression of the cell cycle. He examined a portion of the cells from each sample under a microscope, counting the numbers of cells dividing at each time point at which samples had been taken for protein analysis. Hunt then correlated the amount of the protein present in the cell with the proportion of cells dividing at each time point. He noticed that the level of expression of the protein was highest just before the cell divided and lowest at cell division (Figure 1b), suggesting a correlation with the stage of the cell cycle. When the same experiment was performed in the surf clam, Hunt saw that two of the proteins that he and Ruderman had described previously displayed the same pattern of synthesis and destruction. Hunt called these proteins cyclins to reflect their changing expression through the cell cycle.

Discussion

The discovery of the cyclins heralded an explosion of investigation into the cell cycle. It is now known that these proteins regulate the cell cycle by associating with cyclin-

In addition to the basic research interest in these proteins, the cyclins’ central role in cell division has made them a focal point in cancer research. Cyclins are involved in the regulation of several genes that are known to play prominent roles in tumor development. Scientists have shown that at least one cyclin, cyclin D1, is overexpressed in a number of tumors. The role of these proteins in both normal and aberrant cell division continues to be an active and exciting area of research today.