Epithelial Cells Have Distinct Apical, Lateral, and Basal Surfaces

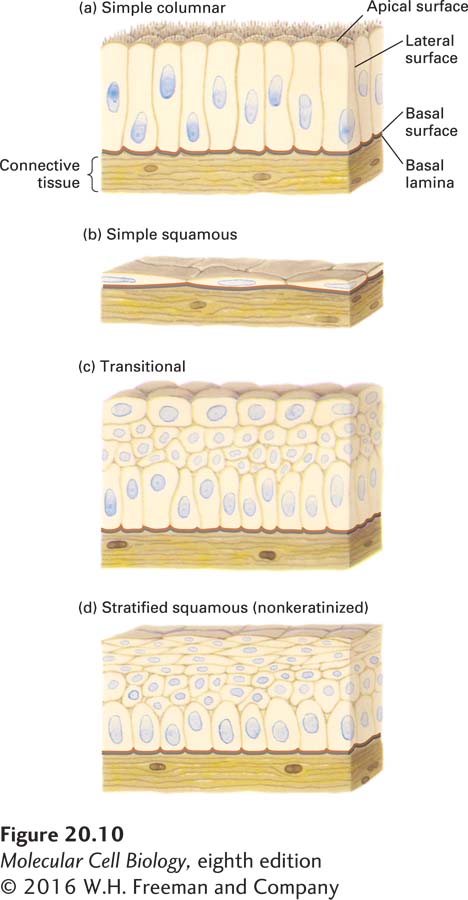

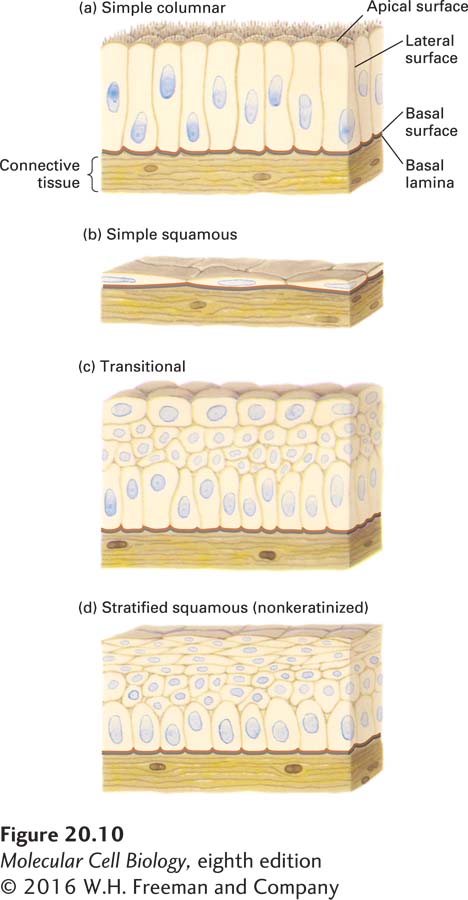

Cells that form epithelial tissues are said to be polarized because their plasma membranes are organized into discrete regions. Typically, the distinct surfaces of a polarized epithelial cell are called the apical (top), lateral (side), and basal (base or bottom) surfaces (Figure 20-10; see also Figure 20-1). The area of the apical surface is often greatly expanded by the formation of microvilli. Adhesion molecules play essential roles in generating and maintaining these distinct surfaces.

FIGURE 20-10 Principal types of epithelia. The apical, lateral, and basal surfaces of epithelial cells can exhibit distinctive characteristics. Often the basal and lateral sides of cells are not distinguishable and are collectively known as the basolateral surface. (a) Simple columnar epithelia consist of elongated cells, including mucus-secreting cells (in the lining of the stomach and cervical tract) and absorptive cells (in the lining of the small intestine). The thin protrusions at the apical surface are microvilli (see Figure 20-11). (b) Simple squamous epithelia, composed of thin cells, line the blood vessels (endothelial cells/endothelium) and many body cavities. (c) Transitional epithelia, composed of several layers of cells with different shapes, line certain cavities subject to expansion and contraction (e.g., the urinary bladder). (d) Stratified squamous (nonkeratinized) epithelia line surfaces such as the mouth and vagina; these linings resist abrasion and generally do not participate in the absorption or secretion of materials into or out of the cavity. The basal lamina, a thin fibrous network of collagen and other ECM components, supports all epithelia and connects them to the underlying connective tissue.

Epithelia in different body locations have characteristic morphologies and functions (see Figure 20-10; see also Figure 1-4). Stratified (multilayered) epithelia commonly serve as barriers and protective surfaces (e.g., the skin), whereas simple (single-layered) epithelia often selectively move ions and small molecules from one side of the epithelium to the other. For instance, the simple columnar epithelium lining the stomach secretes hydrochloric acid into the lumen; a similar epithelium lining the small intestine transports products of digestion from the lumen of the intestine across the cells into the blood (see Figure 11-30).

In simple columnar epithelia, adhesive interactions between the lateral surfaces hold the cells together in a two-dimensional sheet, whereas those at the basal surface connect the cells to a specialized underlying extracellular matrix called the basal lamina. Often the basal and lateral surfaces are similar in composition and are collectively called the basolateral surface. The basolateral surfaces of most simple epithelia are usually on the side of the cell closest to the blood vessels, whereas the apical surface is not in stable, direct contact with other cells or the ECM. In animals with closed circulatory systems, blood flows through vessels whose inner lining is composed of flattened epithelial cells called endothelial cells. In general, epithelial cells are sessile, immobile cells, in that adhesion molecules firmly and stably attach them to one another and their associated ECM. One especially important mechanism that generates strong, stable adhesions is the concentration of subsets of these molecules into clusters called cell junctions.