24.1 How Tumor Cells Differ from Normal Cells

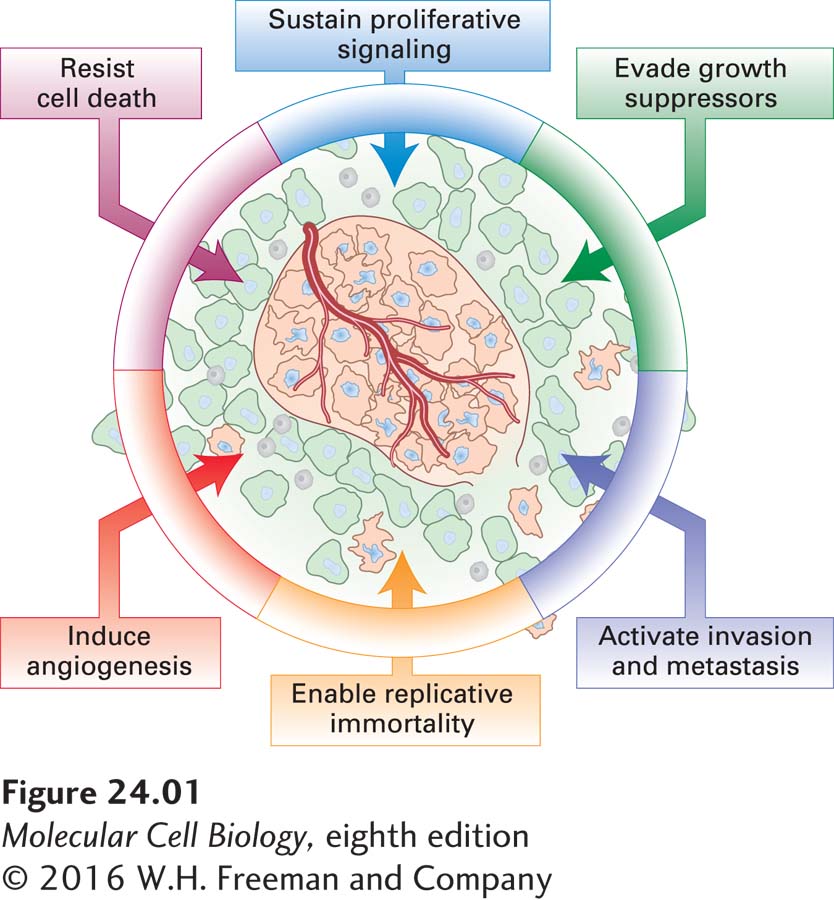

Before examining the genetic basis of cancer in detail, let’s consider the general properties of tumor cells that distinguish them from normal cells. The change from a normal cell to a cancer cell commonly involves multiple steps, each one adding properties that make cells more likely to grow into a tumor. The genetic changes that underlie oncogenesis alter several fundamental properties of cells, allowing those cells to evade normal growth controls and ultimately conferring the full cancer phenotype (Figure 24-1). Cancer cells acquire a drive to proliferate that does not require an external inducing signal. They fail to sense signals that restrict cell division, and they continue to live when they should die. They often change their attachment to surrounding cells or to the extracellular matrix, breaking loose to move away from their tissue of origin. Tumors are characteristically hypoxic (oxygen starved), so to grow to more than a small size, tumors must obtain a blood supply. They often do so by inducing the growth of blood vessels into the tumor. As cancer progresses, a tumor becomes an abnormal organ, increasingly well adapted to growth and invasion of surrounding tissues, and often spreading to distant sites in the body.

1137

In this section, we describe the characteristics of cancer cells. We first discuss the changes in the cancer cell’s genetic makeup that affect virtually all cellular functions, allowing the cancer cell to escape proliferation regulation and acquire the ability to divide indefinitely. We then see how the genetic changes in a tumor cell and its interactions with its environment facilitate its escape from the constraints of the tissue it was once a part of and allow it to invade neighboring tissues and colonize distant sites in the body.