Biological Fluids Have Characteristic pH Values

The solvent inside cells and in all extracellular fluids is water. An important characteristic of any aqueous solution is the concentration of positively charged hydrogen ions (H+) and negatively charged hydroxyl ions (OH–). Because these ions are the dissociation products of H2O, they are constituents of all living systems, and they are liberated by many reactions that take place between molecules within cells. These ions can also be transported into or out of cells, as when highly acidic gastric juice is secreted by cells lining the walls of the stomach.

When a water molecule dissociates, one of its polar H–

H2O ⇌ H+ + OH–

At 25 °C, [H+][OH–] = 10–14 M2, so that in pure water, [H+] = [OH–] = 10–7 M.

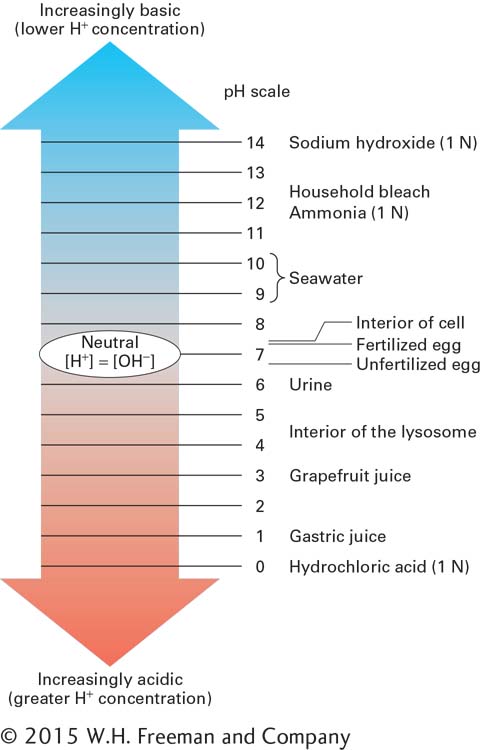

The concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution is expressed conventionally as its pH, defined as the negative log of the hydrogen ion concentration. The pH of pure water at 25 °C is 7:

It is important to keep in mind that a one-

Although the cytosol of cells normally has a pH of about 7.2, the interior of certain organelles in eukaryotic cells (see Chapter 1) can have a much lower pH. The internal (luminal) fluid in lysosomes, for example, has a pH of about 4.5. The many degradative enzymes within lysosomes function optimally in an acidic environment, whereas their action is inhibited in the near neutral pH environment of the cytoplasm. As this example illustrates, maintenance of a particular pH is essential for the proper functioning of some cellular structures. On the other hand, dramatic shifts in cellular pH may play an important role in controlling cellular activity. For example, the pH of the cytoplasm of an unfertilized egg of the sea urchin, an aquatic animal, is 6.6. Within 1 minute of fertilization, however, the pH rises to 7.2; that is, the [H+] decreases to about one-

55