6.4 Locating and Identifying Human Disease Genes

254

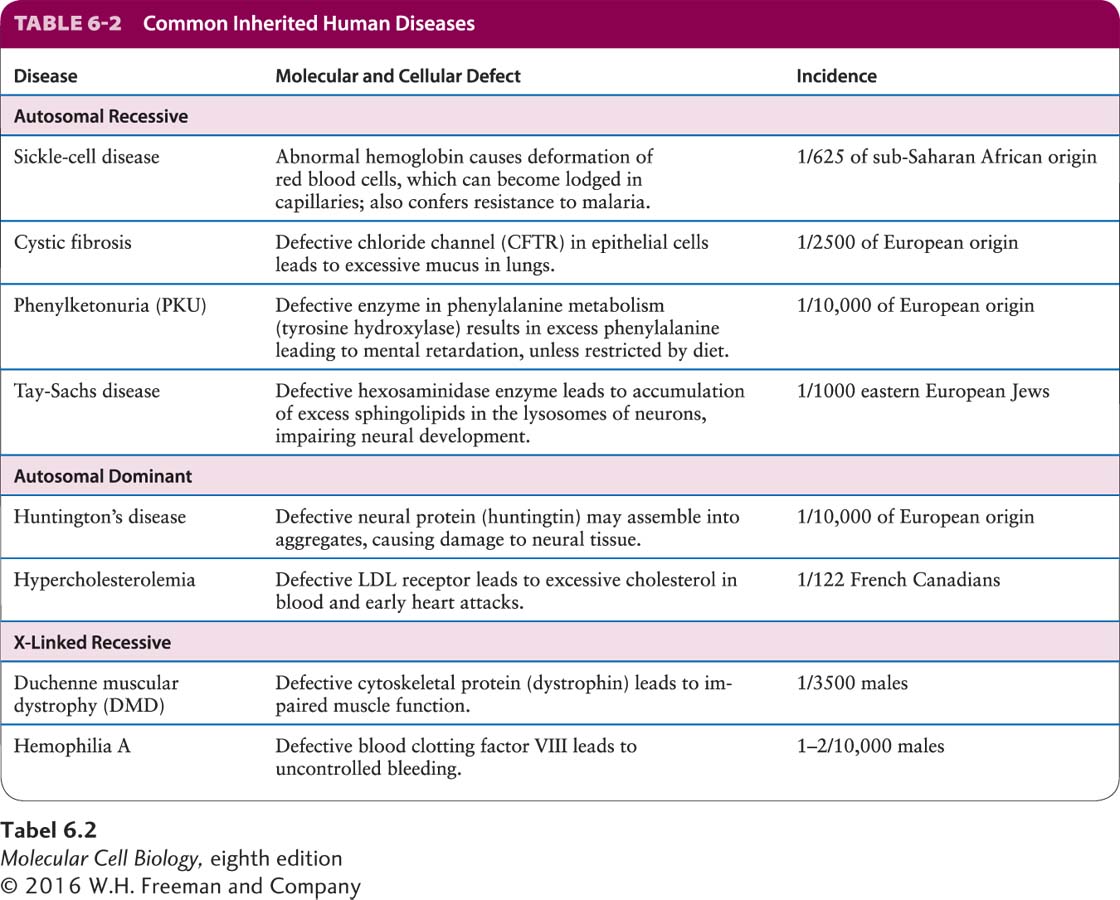

Inherited human diseases are the phenotypic consequence of defective human genes. Table 6-2 lists several of the most commonly occurring inherited diseases. Although a “disease” gene may result from a new mutation that arose in the preceding generation, most cases of inherited diseases are caused by preexisting mutant alleles that have been passed from one generation to the next for many generations.

The typical first step in deciphering the underlying cause of any inherited human disease is to identify the affected gene and its encoded protein. Comparison of the sequences of a disease gene and its product with those of genes and proteins whose sequence and function are known can provide clues to the molecular and cellular cause of the disease. Historically, researchers have used whatever phenotypic clues might be relevant to make guesses about the molecular basis of inherited diseases. An early example of successful guesswork was the hypothesis that sickle-

Most often, however, the genes responsible for inherited diseases must be found without any prior knowledge or reasonable hypotheses about the nature of the affected gene or its encoded protein. In this section, we see how human geneticists can find the gene responsible for an inherited disease by following the segregation of the disease in families. The segregation of the disease can be correlated with the segregation of many other genetic markers, eventually leading to identification of the chromosomal position of the affected gene. This information, along with knowledge of the sequence of the human genome, can ultimately allow the affected gene and the disease-