Aggregate Demand I: Building the IS–LM Model

311

I shall argue that the postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case…. Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience.

—John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory

Of all the economic fluctuations in world history, the one that stands out as particularly large, painful, and intellectually significant is the Great Depression of the 1930s. During this time, the United States and many other countries experienced massive unemployment and greatly reduced incomes. In the worst year, 1933, one-

This devastating episode caused many economists to question the validity of classical economic theory—

In 1936 the British economist John Maynard Keynes revolutionized economics with his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes proposed a new way to analyze the economy, which he presented as an alternative to classical theory. His vision of how the economy works quickly became a center of controversy. Yet, as economists debated The General Theory, a new understanding of economic fluctuations gradually developed.

Keynes proposed that low aggregate demand is responsible for the low income and high unemployment that characterize economic downturns. He criticized classical theory for assuming that aggregate supply alone—

312

Keynes’s ideas about short-

In this chapter and the next, we continue our study of economic fluctuations by looking more closely at aggregate demand. Our goal is to identify the variables that shift the aggregate demand curve, causing fluctuations in national income. We also examine more fully the tools policymakers can use to influence aggregate demand. In Chapter 10, we derived the aggregate demand curve from the quantity theory of money, and we showed that monetary policy can shift the aggregate demand curve. In this chapter, we see that the government can influence aggregate demand with both monetary and fiscal policy.

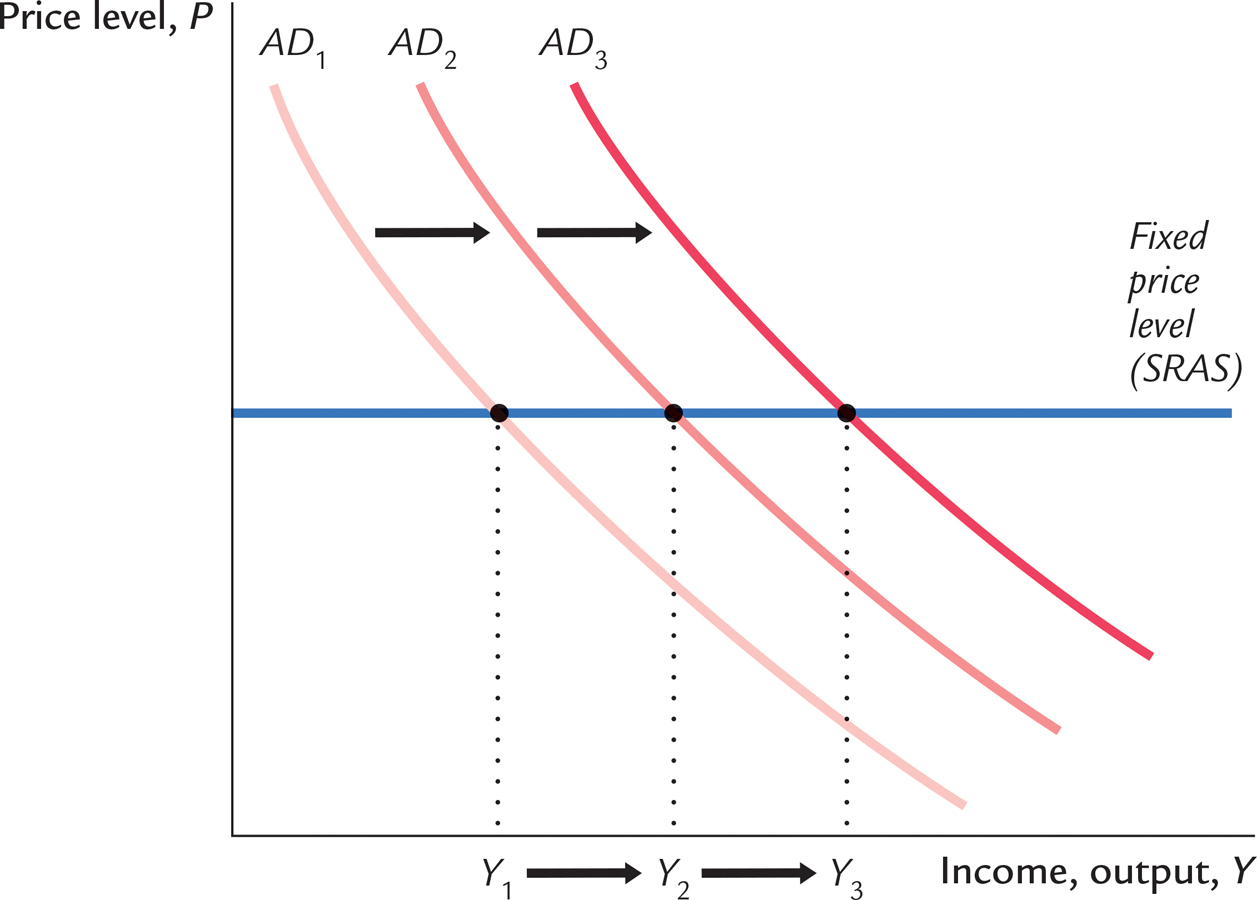

The model of aggregate demand developed in this chapter, called the IS–LM model, is the leading interpretation of Keynes’s theory. The goal of the model is to show what determines national income for a given price level. There are two ways to interpret this exercise. We can view the IS–LM model as showing what causes income to change in the short run when the price level is fixed because all prices are sticky. Or we can view the model as showing what causes the aggregate demand curve to shift. These two interpretations of the model are equivalent: As Figure 11-1 shows, in the short run when the price level is fixed, shifts in the aggregate demand curve lead to changes in the equilibrium level of national income.

The two parts of the IS–LM model are, not surprisingly, the IS curve and the LM curve. IS stands for “investment” and “saving,” and the IS curve represents what’s going on in the market for goods and services (which we first discussed in Chapter 3). LM stands for “liquidity” and “money,” and the LM curve represents what’s happening to the supply and demand for money (which we first discussed in Chapter 5). Because the interest rate influences both investment and money demand, it is the variable that links the two halves of the IS–LM model. The model shows how interactions between the goods and money markets determine the position and slope of the aggregate demand curve and, therefore, the level of national income in the short run.1

313