12.1 Explaining Fluctuations With the IS–LM Model

The intersection of the IS curve and the LM curve determines the level of national income. When one of these curves shifts, the short-

How Fiscal Policy Shifts the IS Curve and Changes the Short-

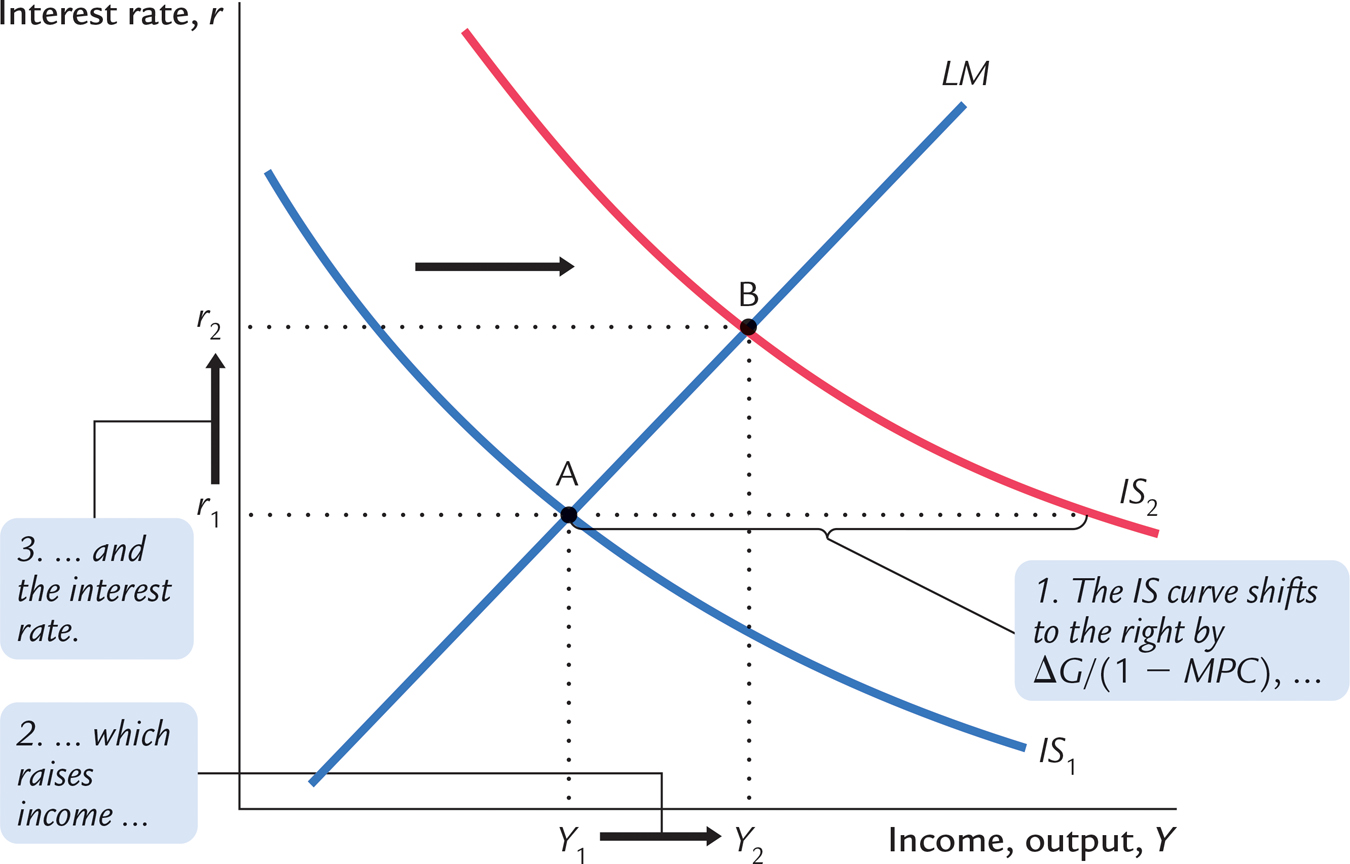

We begin by examining how changes in fiscal policy (government purchases and taxes) alter the economy’s short-

Changes in Government Purchases Consider an increase in government purchases of ΔG. The government-

To understand fully what’s happening in Figure 12-1, it helps to keep in mind the building blocks for the IS–LM model from the preceding chapter—

Now consider the money market, as described by the theory of liquidity preference. Because the economy’s demand for money depends on income, the rise in total income increases the quantity of money demanded at every interest rate. The supply of money, however, has not changed, so higher money demand causes the equilibrium interest rate r to rise.

339

The higher interest rate arising in the money market, in turn, has ramifications back in the goods market. When the interest rate rises, firms cut back on their investment plans. This fall in investment partially offsets the expansionary effect of the increase in government purchases. Thus, the increase in income in response to a fiscal expansion is smaller in the IS–LM model than it is in the Keynesian cross (where investment is assumed to be fixed). You can see this in Figure 12-1. The horizontal shift in the IS curve equals the rise in equilibrium income in the Keynesian cross. This amount is larger than the increase in equilibrium income here in the IS–LM model. The difference is explained by the crowding out of investment due to a higher interest rate.

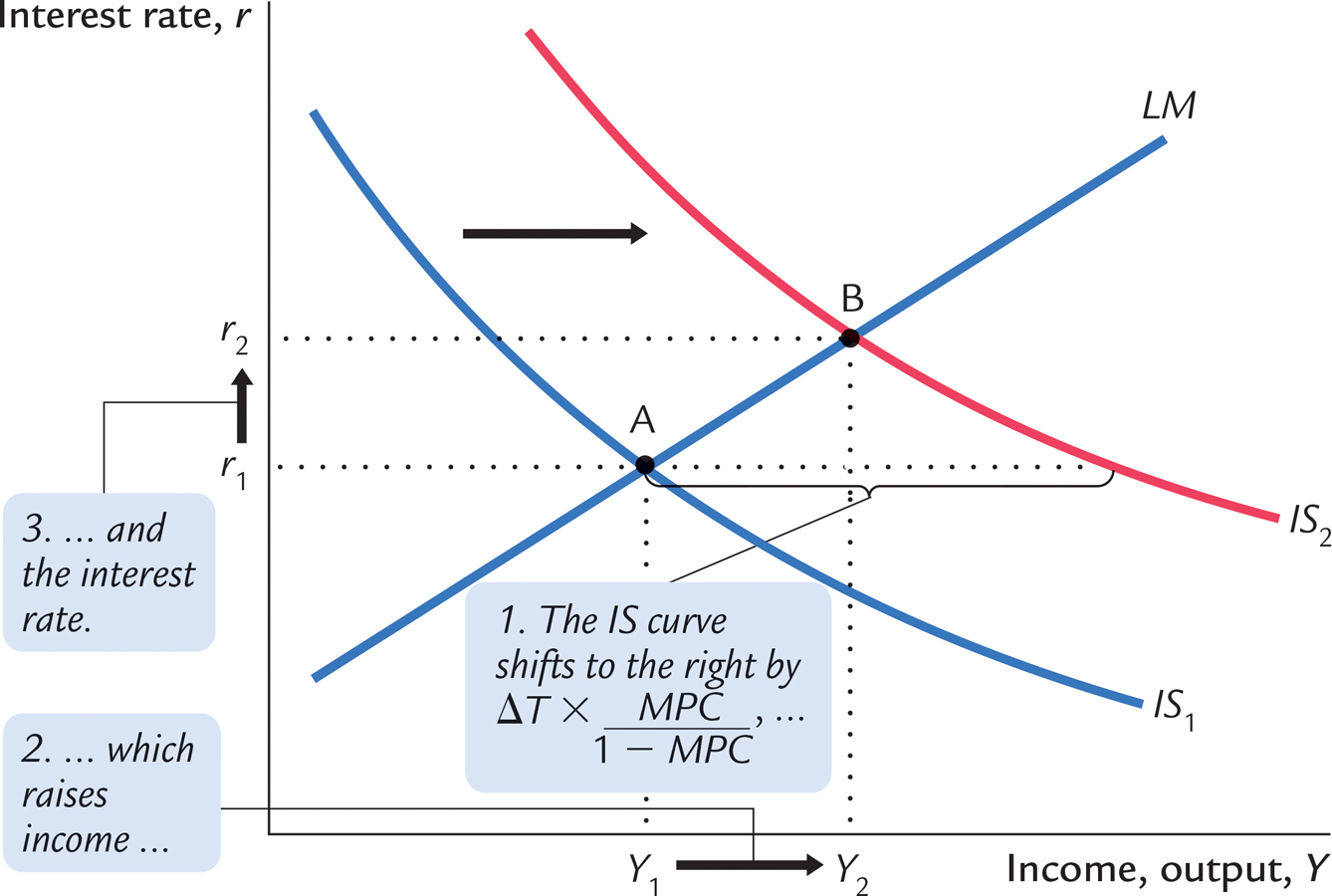

Changes in Taxes In the IS–LM model, changes in taxes affect the economy much the same as changes in government purchases do, except that taxes affect expenditure through consumption. Consider, for instance, a decrease in taxes of ΔT. The tax cut encourages consumers to spend more and, therefore, increases planned expenditure. The tax multiplier in the Keynesian cross tells us that this change in policy raises the level of income at any given interest rate by ΔT × MPC/(1 − MPC). Therefore, as Figure 12-2 illustrates, the IS curve shifts to the right by this amount. The equilibrium of the economy moves from point A to point B. The tax cut raises both income and the interest rate. Once again, because the higher interest rate depresses investment, the increase in income is smaller in the IS–LM model than it is in the Keynesian cross.

340

How Monetary Policy Shifts the LM Curve and Changes the Short-

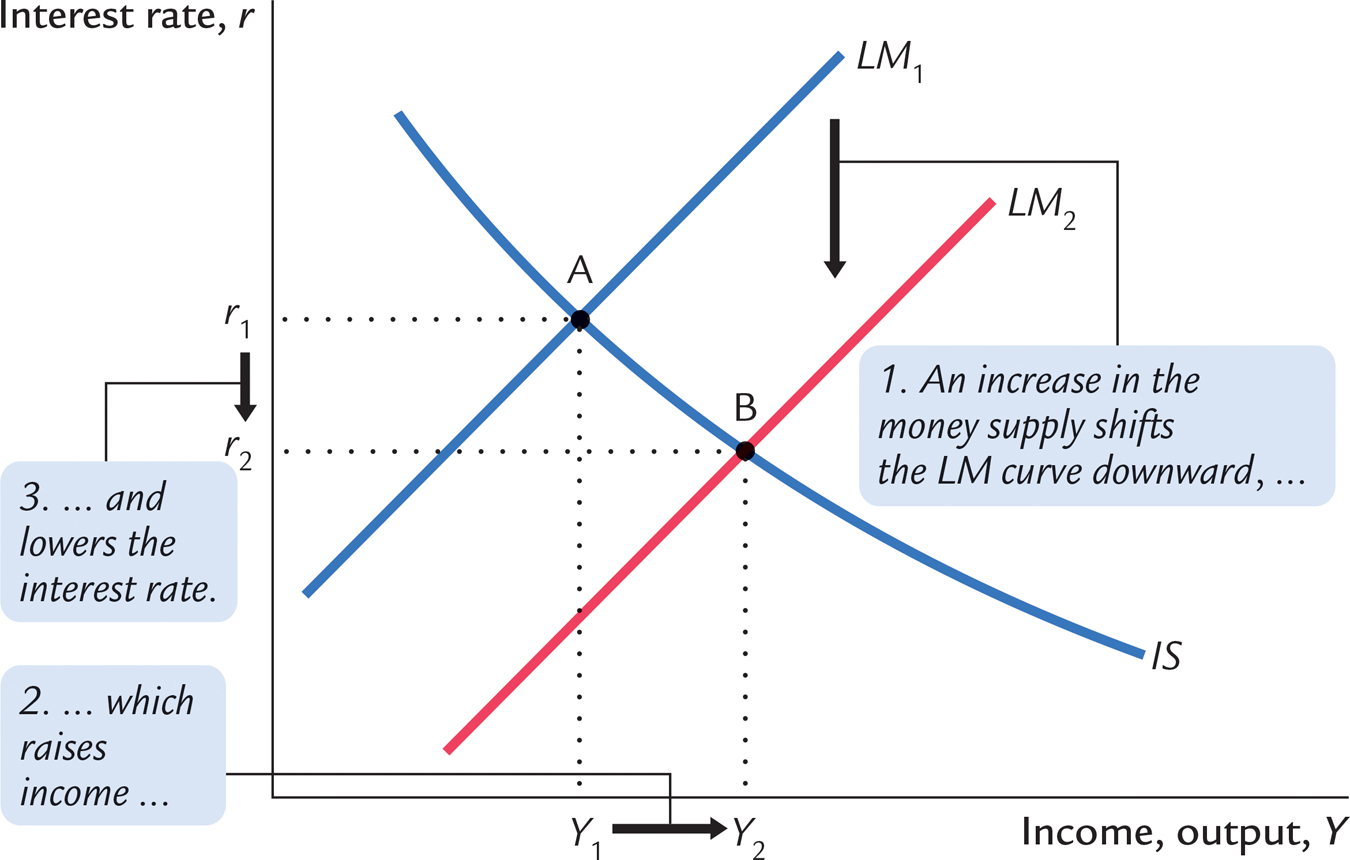

We now examine the effects of monetary policy. Recall that a change in the money supply alters the interest rate that equilibrates the money market for any given level of income and, thus, shifts the LM curve. The IS–LM model shows how a shift in the LM curve affects income and the interest rate.

Consider an increase in the money supply. An increase in M leads to an increase in real money balances M/P because the price level P is fixed in the short run. The theory of liquidity preference shows that for any given level of income, an increase in real money balances leads to a lower interest rate. Therefore, the LM curve shifts downward, as in Figure 12-3. The equilibrium moves from point A to point B. The increase in the money supply lowers the interest rate and raises the level of income.

Once again, to tell the story that explains the economy’s adjustment from point A to point B, we rely on the building blocks of the IS–LM model—

341

Thus, the IS–LM model shows that monetary policy influences income by changing the interest rate. This conclusion sheds light on our analysis of monetary policy in Chapter 10. In that chapter we showed that in the short run, when prices are sticky, an expansion in the money supply raises income. But we did not discuss how a monetary expansion induces greater spending on goods and services—

The Interaction Between Monetary and Fiscal Policy

When analyzing any change in monetary or fiscal policy, it is important to keep in mind that the policymakers who control these policy tools are aware of what the other policymakers are doing. A change in one policy, therefore, may influence the other, and this interdependence may alter the impact of a policy change.

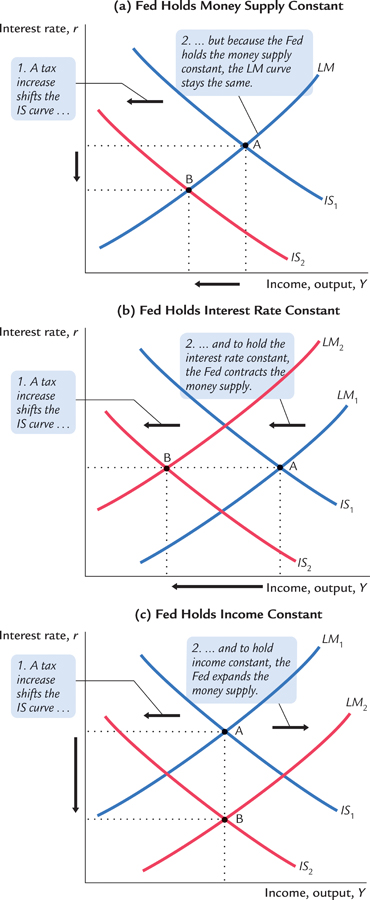

For example, suppose Congress raises taxes. What effect will this policy have on the economy? According to the IS–LM model, the answer depends on how the Fed responds to the tax increase.

Figure 12-4 shows three of the many possible outcomes. In panel (a), the Fed holds the money supply constant. The tax increase shifts the IS curve to the left. Income falls (because higher taxes reduce consumer spending), and the interest rate falls (because lower income reduces the demand for money). The fall in income indicates that the tax hike causes a recession.

342

343

In panel (b), the Fed wants to hold the interest rate constant. In this case, when the tax increase shifts the IS curve to the left, the Fed must decrease the money supply to keep the interest rate at its original level. This fall in the money supply shifts the LM curve upward. The interest rate does not fall, but income falls by a larger amount than if the Fed had held the money supply constant. Whereas in panel (a) the lower interest rate stimulated investment and partially offset the contractionary effect of the tax hike, in panel (b) the Fed deepens the recession by keeping the interest rate high.

In panel (c), the Fed wants to prevent the tax increase from lowering income. It must, therefore, raise the money supply and shift the LM curve downward enough to offset the shift in the IS curve. In this case, the tax increase does not cause a recession, but it does cause a large fall in the interest rate. Although the level of income is not changed, the combination of a tax increase and a monetary expansion does change the allocation of the economy’s resources. The higher taxes depress consumption, while the lower interest rate stimulates investment. Income is not affected because these two effects exactly balance.

From this example we can see that the impact of a change in fiscal policy depends on the policy the Fed pursues—

Shocks in the IS–LM Model

Because the IS–LM model shows how national income is determined in the short run, we can use the model to examine how various economic disturbances affect income. So far we have seen how changes in fiscal policy shift the IS curve and how changes in monetary policy shift the LM curve. Similarly, we can group other disturbances into two categories: shocks to the IS curve and shocks to the LM curve.

Shocks to the IS curve are exogenous changes in the demand for goods and services. Some economists, including Keynes, have emphasized that such changes in demand can arise from investors’ animal spirits—exogenous and perhaps self-

344

Shocks to the IS curve may also arise from changes in the demand for consumer goods. Suppose, for instance, that the election of a popular president increases consumer confidence in the economy. This induces consumers to save less for the future and consume more today. We can interpret this change as an upward shift in the consumption function. This shift in the consumption function increases planned expenditure and shifts the IS curve to the right, and this raises income.

Shocks to the LM curve arise from exogenous changes in the demand for money. For example, suppose that new restrictions on credit card availability increase the amount of money people choose to hold. According to the theory of liquidity preference, when money demand rises, the interest rate necessary to equilibrate the money market is higher (for any given level of income and money supply). Hence, an increase in money demand shifts the LM curve upward, which tends to raise the interest rate and depress income.

In summary, several kinds of events can cause economic fluctuations by shifting the IS curve or the LM curve. Remember, however, that such fluctuations are not inevitable. Policymakers can try to use the tools of monetary and fiscal policy to offset exogenous shocks. If policymakers are sufficiently quick and skillful (admittedly, a big if), shocks to the IS or LM curves need not lead to fluctuations in income or employment.

CASE STUDY

The U.S. Recession of 2001

In 2001, the U.S. economy experienced a pronounced slowdown in economic activity. The unemployment rate rose from 3.9 percent in September 2000 to 4.9 percent in August 2001, and then to 6.3 percent in June 2003. In many ways, the slowdown looked like a typical recession driven by a fall in aggregate demand.

Three notable shocks explain this event. The first was a decline in the stock market. During the 1990s, the stock market experienced a boom of historic proportions, as investors became optimistic about the prospects of the new information technology. Some economists viewed the optimism as excessive at the time, and in hindsight this proved to be the case. When the optimism faded, average stock prices fell by about 25 percent from August 2000 to August 2001. The fall in the market reduced household wealth and thus consumer spending. In addition, the declining perceptions of the profitability of the new technologies led to a fall in investment spending. In the language of the IS–LM model, the IS curve shifted to the left.

345

The second shock was the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001. In the week after the attacks, the stock market fell another 12 percent, which at the time was the biggest weekly loss since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Moreover, the attacks increased uncertainty about what the future would hold. Uncertainty can reduce spending because households and firms postpone some of their plans until the uncertainty is resolved. Thus, the terrorist attacks shifted the IS curve farther to the left.

The third shock was a series of accounting scandals at some of the nation’s most prominent corporations, including Enron and WorldCom. The result of these scandals was the bankruptcy of some companies that had fraudulently represented themselves as more profitable than they truly were, criminal convictions for the executives who had been responsible for the fraud, and new laws aimed at regulating corporate accounting standards more thoroughly. These events further depressed stock prices and discouraged business investment—

Fiscal and monetary policymakers responded quickly to these events. Congress passed a major tax cut in 2001, including an immediate tax rebate, and a second major tax cut in 2003. One goal of these tax cuts was to stimulate consumer spending. (See the Case Study on Cutting Taxes to Stimulate the Economy in Chapter 11.) In addition, after the terrorist attacks, Congress increased government spending by appropriating funds to assist in New York’s recovery and to bail out the ailing airline industry. These fiscal measures shifted the IS curve to the right.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve pursued expansionary monetary policy, shifting the LM curve to the right. Money growth accelerated, and interest rates fell. The interest rate on three-

Expansionary monetary and fiscal policy had the intended effects. Economic growth picked up in the second half of 2003 and was strong throughout 2004. By July 2005, the unemployment rate was back down to 5.0 percent, and it stayed at or below that level for the next several years. Unemployment would begin rising again in 2008, however, when the economy experienced another recession. The causes of the 2008 recession are examined in another Case Study later in this chapter.

What Is the Fed’s Policy Instrument—The Money Supply or the Interest Rate?

Our analysis of monetary policy has been based on the assumption that the Fed influences the economy by controlling the money supply. By contrast, when the media report on changes in Fed policy, they often just say that the Fed has raised or lowered interest rates. Which is right? Even though these two views may seem different, both are correct, and it is important to understand why.

346

In recent years, the Fed has used the federal funds rate—the interest rate that banks charge one another for overnight loans—

As a result of this operating procedure, Fed policy is often discussed in terms of changing interest rates. Keep in mind, however, that behind these changes in interest rates are the necessary changes in the money supply. A newspaper might report, for instance, that “the Fed has lowered interest rates.” To be more precise, we can translate this statement as meaning “the Federal Open Market Committee has instructed the Fed bond traders to buy bonds in open-

Why has the Fed chosen to use an interest rate, rather than the money supply, as its short-

In Chapter 15 we extend our theory of short-