15.1 Elements of the Model

Before examining the components of the dynamic AD–AS model, we need to introduce one piece of notation: Throughout this chapter, the subscript t on a variable represents time. For example, Y is used to represent total output and national income, as it has been throughout this book. But now it takes the form Yt, which represents output in time period t. Similarly, Yt−1 represents output in period t − 1, and Yt+1 represents output in period t + 1. This new notation will allow us to keep track of variables as they change over time.

Let’s now look at the five equations that make up the dynamic AD–AS model.

Output: The Demand for Goods and Services

The demand for goods and services is given by the equation

where Yt is the total output of goods and services,  is the economy’s natural level of output, rt is the real interest rate, εt is a random demand shock, and α and ρ are parameters greater than zero. This equation is similar in spirit to the demand for goods and services equation in Chapter 3 and the IS equation in Chapter 11. Because this equation is so central to the dynamic AD–AS model, let’s examine each of the terms with some care.

is the economy’s natural level of output, rt is the real interest rate, εt is a random demand shock, and α and ρ are parameters greater than zero. This equation is similar in spirit to the demand for goods and services equation in Chapter 3 and the IS equation in Chapter 11. Because this equation is so central to the dynamic AD–AS model, let’s examine each of the terms with some care.

441

The key feature of this equation is the negative relationship between the real interest rate rt and the demand for goods and services Yt. When the real interest rate increases, borrowing becomes more expensive, and saving yields a greater reward. As a result, firms engage in fewer investment projects, and consumers save more and spend less. Both of these effects reduce the demand for goods and services. (In addition, the dollar might appreciate in foreign-exchange markets, causing net exports to fall, but for our purposes in this chapter these open-economy effects need not play a central role and can largely be ignored.) The parameter α tells us how sensitive demand is to changes in the real interest rate. The larger the value of α, the more the demand for goods and services responds to a given change in the real interest rate.

The first term on the right-hand side of the equation,  , implies that the demand for goods and services Yt rises with the economy’s natural level of output

, implies that the demand for goods and services Yt rises with the economy’s natural level of output  . In most cases, we can simplify the analysis by assuming that

. In most cases, we can simplify the analysis by assuming that  is constant (that is, the same for every time period t). Later in the chapter, however, we examine how this model can take into account long-run growth, represented by exogenous increases in

is constant (that is, the same for every time period t). Later in the chapter, however, we examine how this model can take into account long-run growth, represented by exogenous increases in  over time. Holding other things constant, as long-run growth increases the economy’s ability to supply goods and services (measured by the natural level of output), it also makes the economy richer and increases the demand for goods and services.

over time. Holding other things constant, as long-run growth increases the economy’s ability to supply goods and services (measured by the natural level of output), it also makes the economy richer and increases the demand for goods and services.

The last term in the demand equation, εt, represents exogenous shifts in demand. Think of εt as a random variable—a variable whose values are determined by chance. It is zero on average but fluctuates over time. For example, if (as Keynes famously suggested) investors are driven in part by “animal spirits”—irrational waves of optimism and pessimism—those changes in sentiment would be captured by εt. When investors become optimistic, they increase their demand for goods and services, represented here by a positive value of εt. When they become pessimistic, they cut back on spending, and εt is negative.

Next, consider the parameter ρ. We call ρ the natural rate of interest because it is the real interest rate at which, in the absence of any shock, the demand for goods and services equals the natural level of output. That is, if εt = 0 and rt = ρ, then Yt =  . Later in the chapter, we see that the real interest rate rt tends to move toward the natural rate of interest ρ in the long run. Throughout this chapter, we assume that the natural rate of interest is constant (that is, the same in every period). Problem 7 at the end of the chapter examines what happens if it changes.

. Later in the chapter, we see that the real interest rate rt tends to move toward the natural rate of interest ρ in the long run. Throughout this chapter, we assume that the natural rate of interest is constant (that is, the same in every period). Problem 7 at the end of the chapter examines what happens if it changes.

Finally, a word about how monetary and fiscal policy influences the demand for goods and services. Monetary policymakers affect demand by changing the real interest rate rt. Thus, their actions work through the second term in this equation. By contrast, when fiscal policymakers alter taxes or government spending, they change demand for any given interest rate. As a result, the variable εt captures changes in fiscal policy. An increase in government spending or a tax cut that stimulates consumer spending means a positive value of εt. A cut in government spending or a tax hike means a negative value of εt. As we will see, one purpose of this model is to examine the dynamic effects of changes in monetary and fiscal policy.

442

The Real Interest Rate: The Fisher Equation

The real interest rate in this model is defined as it has been in earlier chapters. The real interest rate rt is the nominal interest rate it minus the expected rate of future inflation Etπt+1. That is,

rt = it − Etπt+1.

This Fisher equation is similar to the one we first saw in Chapter 5. Here, Etπt+1 represents the expectation formed in period t of inflation in period t + 1. The variable rt is the ex ante real interest rate: the real interest rate that people anticipate based on their expectation of inflation.

A word on the notation and timing convention should clarify the meaning of these variables. The variables rt and it are interest rates that prevail at time t and, therefore, represent a rate of return between periods t and t + 1. The variable πt denotes the current inflation rate, which is the percentage change in the price level between periods t − 1 and t. Similarly, πt+1 is the percentage change in the price level that will occur between periods t and t + 1. As of period t, πt+1 represents a future inflation rate and therefore is not yet known. In period t, people can form an expectation of πt+1 (written as Etπt+1), but they will have to wait until period t + 1 to learn the actual value of πt+1 and whether their expectation was correct.

Note that the subscript on a variable tells us when the variable is determined. The nominal and ex ante real interest rates between t and t + 1 are known at time t, so they are written as it and rt. By contrast, the inflation rate between t and t + 1 is not known until time t + 1, so it is written as πt+1.

This subscript rule also applies when the expectations operator E precedes a variable, but here you have to be especially careful. As in previous chapters, the operator E in front of a variable denotes the expectation of that variable prior to its realization. The subscript on the expectations operator tells us when that expectation is formed. So Etπt+1 is the expectation of what the inflation rate will be in period t + 1 (the subscript on π) based on information available in period t (the subscript on E). While the inflation rate πt+1 is not known until period t + 1, the expectation of future inflation, Etπt+1, is known at period t. As a result, even though the ex post real interest rate, which is given by it − πt+1, will not be known until period t + 1, the ex ante real interest rate, rt = it − Etπt+1, is known at time t.

Inflation: The Phillips Curve

Inflation in this economy is determined by a conventional Phillips curve augmented to include roles for expected inflation and exogenous supply shocks. The equation for inflation is

This piece of the model is similar to the Phillips curve and short-run aggregate supply equation introduced in Chapter 14. According to this equation, inflation πt depends on previously expected inflation Et−1πt, the deviation of output from its natural level  , and an exogenous supply shock υt.

, and an exogenous supply shock υt.

443

Inflation depends on expected inflation because some firms set prices in advance. When these firms expect high inflation, they anticipate that their costs will be rising quickly and that their competitors will be implementing substantial price hikes. The expectation of high inflation thereby induces these firms to announce significant price increases for their own products. These price increases in turn cause high actual inflation in the overall economy. Conversely, when firms expect low inflation, they forecast that costs and competitors’ prices will rise only modestly. In this case, they keep their own price increases down, leading to low actual inflation.

The parameter ϕ, which is greater than zero, tells us how much inflation responds when output fluctuates around its natural level. Other things equal, when the economy is booming and output rises above its natural level  , firms experience increasing marginal cost, so they raise prices; these price hikes increase inflation πt. When the economy is in a slump and output is below its natural level

, firms experience increasing marginal cost, so they raise prices; these price hikes increase inflation πt. When the economy is in a slump and output is below its natural level  , marginal cost falls, and firms cut prices; these price cuts reduce inflation πt. The parameter ϕ reflects both how much marginal cost responds to the state of economic activity and how quickly firms adjust prices in response to changes in cost.

, marginal cost falls, and firms cut prices; these price cuts reduce inflation πt. The parameter ϕ reflects both how much marginal cost responds to the state of economic activity and how quickly firms adjust prices in response to changes in cost.

In this model, the state of the business cycle is measured by the deviation of output from its natural level  . The Phillips curves in Chapter 14 sometimes emphasized the deviation of unemployment from its natural rate. This difference is not significant, however. Recall Okun’s law from Chapter 10: short-run fluctuations in output and unemployment are strongly and negatively correlated. When output is above its natural level, unemployment is below its natural rate, and vice versa. As we continue to develop this model, keep in mind that unemployment fluctuates along with output, but in the opposite direction.

. The Phillips curves in Chapter 14 sometimes emphasized the deviation of unemployment from its natural rate. This difference is not significant, however. Recall Okun’s law from Chapter 10: short-run fluctuations in output and unemployment are strongly and negatively correlated. When output is above its natural level, unemployment is below its natural rate, and vice versa. As we continue to develop this model, keep in mind that unemployment fluctuates along with output, but in the opposite direction.

The supply shock υt is a random variable that averages to zero but can, in any given period, be positive or negative. This variable captures all influences on inflation other than expectations of inflation (which is captured in the first term, Et−1πt) and short-run economic conditions [which are captured in the second term,  ]. For example, if an aggressive oil cartel pushes up world oil prices, thus increasing overall inflation, that event would be represented by a positive value of υt. If cooperation within the oil cartel breaks down and world oil prices plummet, causing inflation to fall, υt would be negative. In short, υt reflects all exogenous events that directly influence inflation.

]. For example, if an aggressive oil cartel pushes up world oil prices, thus increasing overall inflation, that event would be represented by a positive value of υt. If cooperation within the oil cartel breaks down and world oil prices plummet, causing inflation to fall, υt would be negative. In short, υt reflects all exogenous events that directly influence inflation.

Expected Inflation: Adaptive Expectations

As we have seen, expected inflation plays a key role in both the Phillips curve equation for inflation and the Fisher equation relating nominal and real interest rates. To keep the dynamic AD–AS model simple, we assume that people form their expectations of inflation based on the inflation they have recently observed. That is, people expect prices to continue rising at the same rate they have been rising. As noted in Chapter 14, this is sometimes called the assumption of adaptive expectations. It can be written as

444

Etπt+1 = πt.

When forecasting in period t what inflation rate will prevail in period t + 1, people simply look at inflation in period t and extrapolate it forward.

The same assumption applies in every period. Thus, when inflation was observed in period t − 1, people expected that rate to continue. This implies that Et−1πt = πt−1.

This assumption about inflation expectations is admittedly crude. Many people are probably more sophisticated in forming their expectations. As we discussed in Chapter 14, some economists advocate an approach called rational expectations, according to which people optimally use all available information when forecasting the future. Incorporating rational expectations into the model is, however, beyond the scope of this book. (Moreover, the empirical validity of rational expectations is open to dispute.) The assumption of adaptive expectations greatly simplifies the exposition of the theory without losing many of the model’s insights.

The Nominal Interest Rate: The Monetary-Policy Rule

The last piece of the model is the equation for monetary policy. We assume that the central bank sets a target for the nominal interest rate it based on inflation and output using this rule:

In this equation,  is the central bank’s target for the inflation rate. (For most purposes, target inflation can be assumed to be constant, but we will keep a time subscript on this variable so we can later examine what happens when the central bank changes its target.) Two key policy parameters are θπ and θY, which are both assumed to be greater than zero. They indicate how much the central bank allows the interest rate target to respond to fluctuations in inflation and output. The larger the value of θπ, the more responsive the central bank is to the deviation of inflation from its target; the larger the value of θY, the more responsive the central bank is to the deviation of output from its natural level. Recall that ρ, the constant in this equation, is the natural rate of interest (the real interest rate at which, in the absence of any shock, the demand for goods and services equals the natural level of output). This equation tells us how the central bank uses monetary policy to respond to any situation it faces. That is, it tells us how the target for the nominal interest rate chosen by the central bank responds to macroeconomic conditions.

is the central bank’s target for the inflation rate. (For most purposes, target inflation can be assumed to be constant, but we will keep a time subscript on this variable so we can later examine what happens when the central bank changes its target.) Two key policy parameters are θπ and θY, which are both assumed to be greater than zero. They indicate how much the central bank allows the interest rate target to respond to fluctuations in inflation and output. The larger the value of θπ, the more responsive the central bank is to the deviation of inflation from its target; the larger the value of θY, the more responsive the central bank is to the deviation of output from its natural level. Recall that ρ, the constant in this equation, is the natural rate of interest (the real interest rate at which, in the absence of any shock, the demand for goods and services equals the natural level of output). This equation tells us how the central bank uses monetary policy to respond to any situation it faces. That is, it tells us how the target for the nominal interest rate chosen by the central bank responds to macroeconomic conditions.

To interpret this equation, it is best to focus not just on the nominal interest rate it but also on the real interest rate rt. Recall that the demand for goods and services depends on the real interest rate, not on the nominal interest rate. So, although the central bank sets a target for the nominal interest rate it, the bank’s influence on the economy works through the real interest rate rt. By definition, the real interest rate is rt = it − Etπt+1, but with our expectation equation Etπt+1 = πt, we can also write the real interest rate as rt = it − πt. According to the equation for monetary policy, if inflation is at its target  and output is at its natural level

and output is at its natural level  , the last two terms in the equation are zero, so the real interest rate equals the natural rate of interest ρ. As inflation rises above its target

, the last two terms in the equation are zero, so the real interest rate equals the natural rate of interest ρ. As inflation rises above its target  or output rises above its natural level

or output rises above its natural level  , the real interest rate rises. And as inflation falls below its target

, the real interest rate rises. And as inflation falls below its target  or output falls below its natural level

or output falls below its natural level  , the real interest rate falls.

, the real interest rate falls.

445

At this point, one might naturally ask, “What about the money supply?” In previous chapters, such as Chapter 11 and Chapter 12, the money supply was typically taken to be the policy instrument of the central bank, and the interest rate adjusted to bring money supply and money demand into equilibrium. Here, we turn that logic on its head. The central bank is assumed to set a target for the nominal interest rate. It then adjusts the money supply to whatever level is necessary to ensure that the equilibrium interest rate (which balances money supply and demand) hits the target.

The main advantage of using the interest rate, rather than the money supply, as the policy instrument in the dynamic AD–AS model is that it is more realistic. Today, most central banks, including the Federal Reserve, set a short-term target for the nominal interest rate. Keep in mind, though, that hitting that target requires adjustments in the money supply. For this model, we do not need to specify the equilibrium condition for the money market, but we should remember that it is lurking in the background. When a central bank decides to change the interest rate, it is also committing itself to adjust the money supply accordingly.

CASE STUDY

The Taylor Rule

If you wanted to set interest rates to achieve low, stable inflation while avoiding large fluctuations in output and employment, how would you do it? This is exactly the question that the governors of the Federal Reserve must ask themselves every day. The short-term policy instrument that the Fed now sets is the federal funds rate—the short-term interest rate at which banks make loans to one another. Whenever the Federal Open Market Committee meets, it chooses a target for the federal funds rate. The Fed’s bond traders are then told to conduct open-market operations to hit the desired target.

The hard part of the Fed’s job is choosing the target for the federal funds rate. Two general guidelines are clear. First, when inflation heats up, the federal funds rate should rise. An increase in the interest rate will mean a smaller money supply and, eventually, lower investment, lower output, higher unemployment, and reduced inflation. Second, when real economic activity slows—as reflected in real GDP or unemployment—the federal funds rate should fall. A decrease in the interest rate will mean a larger money supply and, eventually, higher investment, higher output, and lower unemployment. These two guidelines are represented by the monetary-policy equation in the dynamic AD–AS model.

446

The Fed needs to go beyond these general guidelines, however, and decide exactly how much to respond to changes in inflation and real economic activity. Stanford University economist John Taylor has proposed the following rule for the federal funds rate:1

Nominal Federal Funds Rate = Inflation + 2.0 + 0.5 (Inflation − 2.0) + 0.5 (GDP gap).

The GDP gap is the percentage by which real GDP deviates from an estimate of its natural level. (For consistency with our dynamic AD–AS model, the GDP gap here is taken to be positive if GDP rises above its natural level and negative if it falls below it.)

According to the Taylor rule, the real federal funds rate—the nominal rate minus inflation—should respond to inflation and the GDP gap. According to this rule, the real federal funds rate equals 2 percent when inflation is 2 percent and GDP is at its natural level. The first constant of 2 percent in this equation can be interpreted as an estimate of the natural rate of interest ρ, and the second constant of 2 percent subtracted from inflation can be interpreted as the Fed’s inflation target  . For each percentage point that inflation rises above 2 percent, the real federal funds rate rises by 0.5 percent. For each percentage point that real GDP rises above its natural level, the real federal funds rate rises by 0.5 percent. If inflation falls below 2 percent or GDP moves below its natural level, the real federal funds rate falls accordingly.

. For each percentage point that inflation rises above 2 percent, the real federal funds rate rises by 0.5 percent. For each percentage point that real GDP rises above its natural level, the real federal funds rate rises by 0.5 percent. If inflation falls below 2 percent or GDP moves below its natural level, the real federal funds rate falls accordingly.

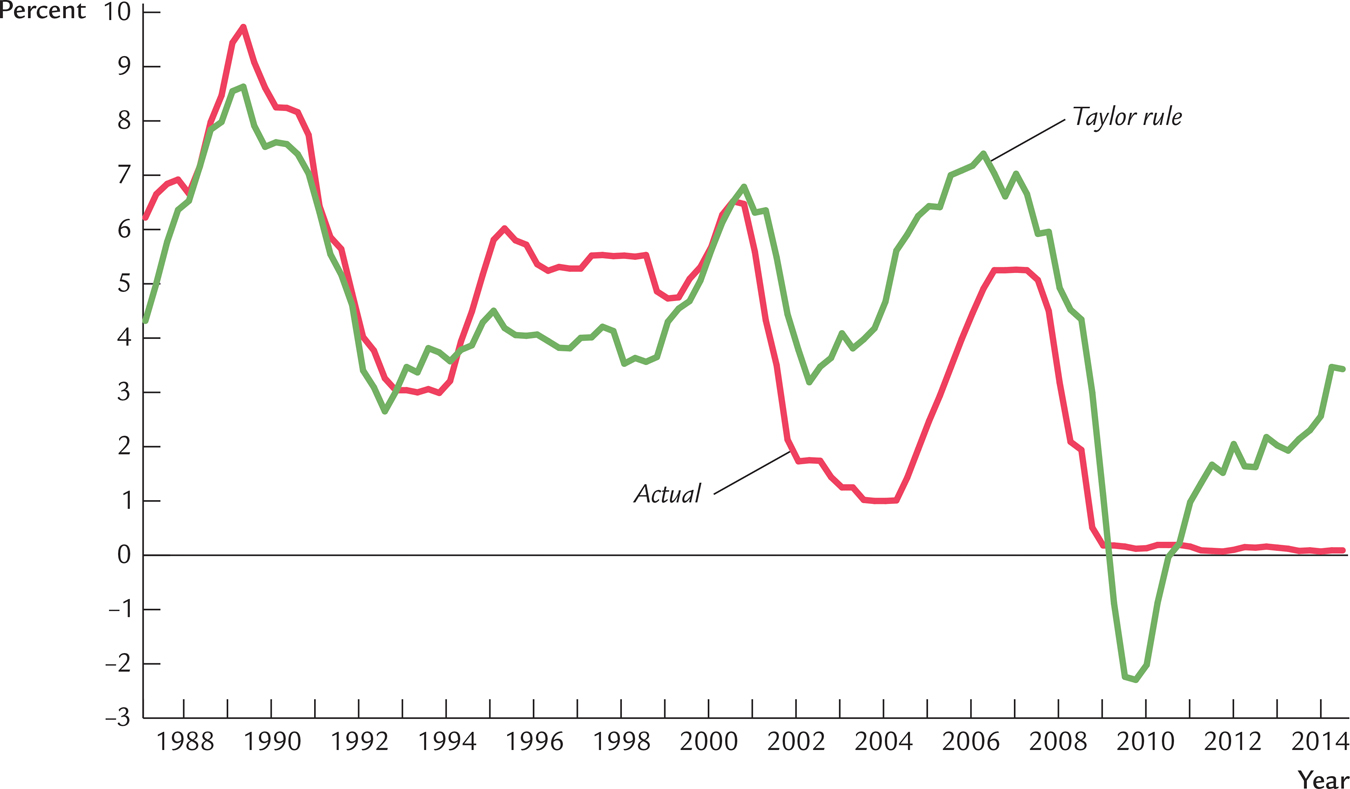

In addition to being simple and reasonable, the Taylor rule for monetary policy also resembles actual Fed behavior in recent years. Figure 15-1 shows the actual nominal federal funds rate and the target rate as determined by Taylor’s proposed rule. Notice how the two series tend to move together. John Taylor’s monetary rule may be more than an academic suggestion. To some degree, it may be the rule that the Federal Reserve governors subconsciously follow.

Notice that if inflation and output are both low enough, the Taylor rule can prescribe a negative nominal interest rate. That circumstance in fact arose in the aftermath of the financial crisis and deep recession of 2008–2009. Such a policy is not feasible, however. As we saw in the discussion of the liquidity trap in Chapter 12, a central bank cannot set a negative nominal interest rate because people would just hold currency (which pays a zero nominal return) instead of lending at a negative rate. In these circumstances, the Taylor rule cannot be strictly followed. The closest a central bank can come to following the rule is to set the interest rate at about zero, as in fact the Fed did during this period.

The Taylor rule started recommending an increase in the federal funds rate around 2011. The Federal Reserve, however, kept the interest rates at about zero. This recent discrepancy has been a source of policy debate. Some economists argue that the Fed’s policy was appropriate to make up for the period when interest rates were above the negative levels the rule advised. That is, they believe that to help the economy recover from the deep recession, a period of below-rule interest rates was needed to compensate for the preceding period of above-rule interest rates. Other economists, however, argue that the Fed was too slow to raise interest rates as the economy recovered from the recession. They fear that continued low interest rates might sow the seeds of future inflationary pressures.

447